Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

When Lauretta Morton, director of Newcastle Art Gallery, first proposed an exhibition devoted to Torres Strait Island art, the reaction from some quarters was one of incredulity to the point of derision.

“When I first floated the idea, I was met with quite a bit of criticism,” says Morton, “with several comments like, ‘Why would you do a Torres Strait Islands exhibition in Newcastle?’ To be honest, even though it was risky, it just made me want to do it even more.”

And on the surface it may seem strange to stage a historical and diverse survey of Torres Strait art in a relatively small East Coast city arguably best known for its mining industry, its port, its beaches and its rugby league team. But Morton’s passion and persistence, in combination with the innovation and knowledge of curator, and artist Brian Robinson, has resulted in a landmark exhibition that embraces the art-making, traditions and customs of the Torres Strait going back as far as the 18th century.

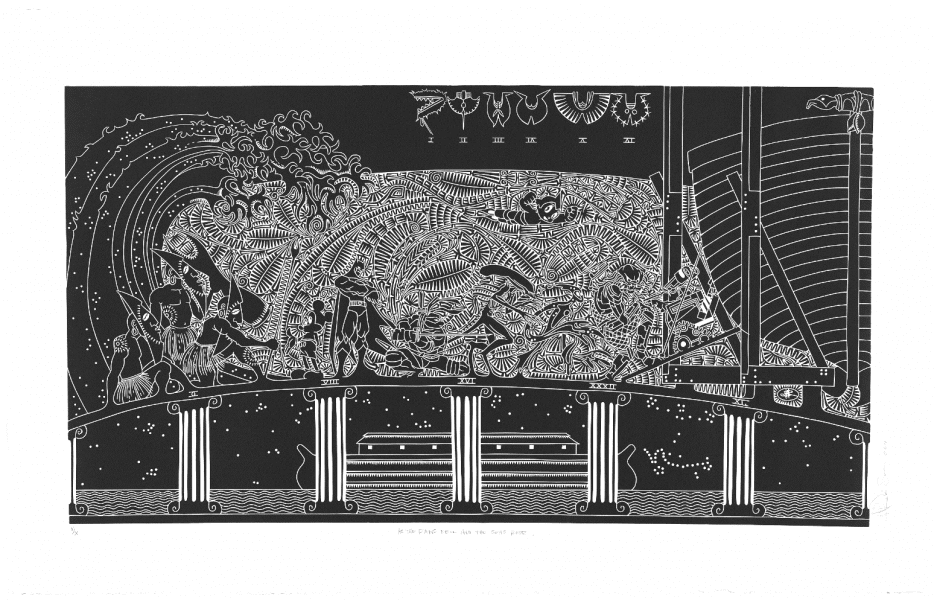

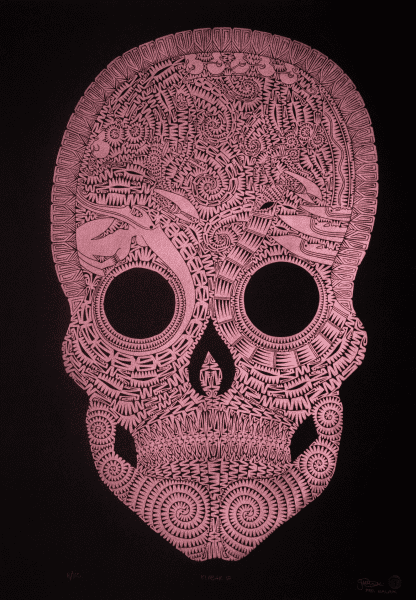

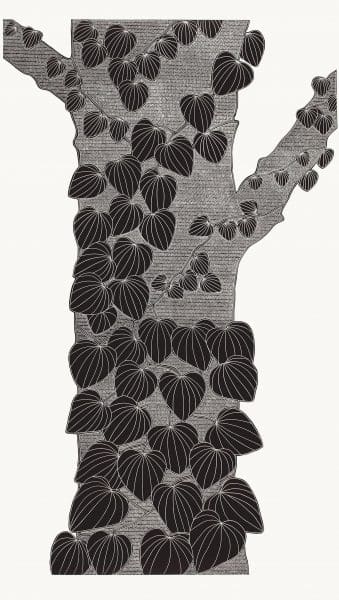

WARWAR: The Art of Torres Strait is unprecedented in several ways. For one, it is the first Torres Strait art exhibition on this scale (no fewer than 130 works are on display) ever held outside a major city. For another, some works have never been seen outside of the Torres Strait. Artists involved include Newcastle’s own Toby Cedar, whose works Op Nor Beizam (Shark Mask) White and Op Nor Beizam (Shark Mask) Pearl, both 2018, are true centrepieces of the show, along with Joseph Au, Ken Thaiday, Glen Mackie, Billy Missi and myriad others. Artists showing their work for the first time outside of the Torres Strait are Badhulgaw Kuthinaw Mudh (Badu Art Centre), Ngalmun Lagau Minaral (Moa Arts) and Erub Erwer Meta (Erub Arts). Artworks range from works on paper and paintings through to masks of multiple varieties, dance paraphernalia, sculpture, textiles and plenty more.

The genesis of WARWAR can be traced back to 2017, when Morton approached Robinson to curate a Torres Strait-focused show, after the latter had exhibited as part of Sydney Contemporary. Robinson, as Morton explains, brought “intimate knowledge and understanding of Torres Strait Islander arts practice” and “completely understood that this was a landmark exhibition for Newcastle Art Gallery and that we needed to tell the story of the evolution and strength of Torres Strait tradition and culture throughout the project.”

Robinson has divided the show into four historical categories: the 18th and 19th centuries; the 1900s to the 1980s; the art that emerged between 1980 and 2000; and contemporary arts practice since 2000. Robinson is also responsible for the exhibition’s name.

“One common theme that threads through all the works is covered in the title,” says Robinson, who grew up on Thursday Island in the Torres Strait and is now based in Cairns. “‘Warwar’ translates into English as ‘marked with a pattern.’ Every work on display references a unique pattern that has a long tradition within Torres Strait. This pattern can be found etched into the surface of objects, woven into baskets, mats and other textiles, and printed and painted on objects.”

As well as this commitment to cultural symbolism and tradition, it seems that Robinson has prioritised two further major ideas in his curatorship. One is a challenge to the tyranny of categorisation, or more specifically, an assertion of Torres Strait identity in the context of the common classification ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander.’ WARWAR seeks to distinguish Torres Strait Island art as its own distinct entity, with its own tradition.

“Knowledge of Torres Strait culture within the Australian and international community is generally subsumed under the Indigenous umbrella of Aboriginal Australia,” says Robinson. “This denies the inherent cultural differences that exist between the groups. The development and recognition of contemporary art from the area is a positive step towards acknowledgement of the area, of the people, of the culture.”

Robinson adds that works in WARWAR only touch on social or political issues “in a minimal way,” although the exhibition touts itself as exploring cultural maintenance, Christianity, language, environment and globalisation – all of which lend themselves to wider geopolitical contexts, including the legacy of colonialism.

The other key idea that Robinson and Morton emphasise in the show is that Torres Strait is a cultural identity as much as it is a place on a map. In essence, WARWAR makes the point that Torres Strait Island art does not necessarily have to come directly from the Torres Strait itself, with people with links to the islands scattered across the continent – including the Newcastle region.

“The exhibition provides an important opportunity for us to engage with our Torres Strait Islander community,” says Morton, “many of whom are second and third-generation, Newcastle-born. They can experience their own culture through works of art created by their ancestors.”

Robinson adds, “WARWAR is an exhibition that instils a spirit and slowly seduces the viewer, revealing some of the secrets, narratives and cultural life bound to Torres Strait that have slowly filtered across the continent where communities of Torres Strait islanders reside.

“The development of Torres Strait art over the past 20 years has seen an increase in its complexity, diversity and popularity. For all the artists, regardless of where they reside, there is a desire to not only revive the old stories and objects of the past, but to also show the importance of identity, ensuring that islanders can reconnect with tradition.”

Covid-19 restrictions permitting, NAIDOC week celebrations will take place in the gallery on Saturday 10 July at 2pm.

WARWAR: The Art of Torres Strait

Newcastle Art Gallery

29 May – 22 August