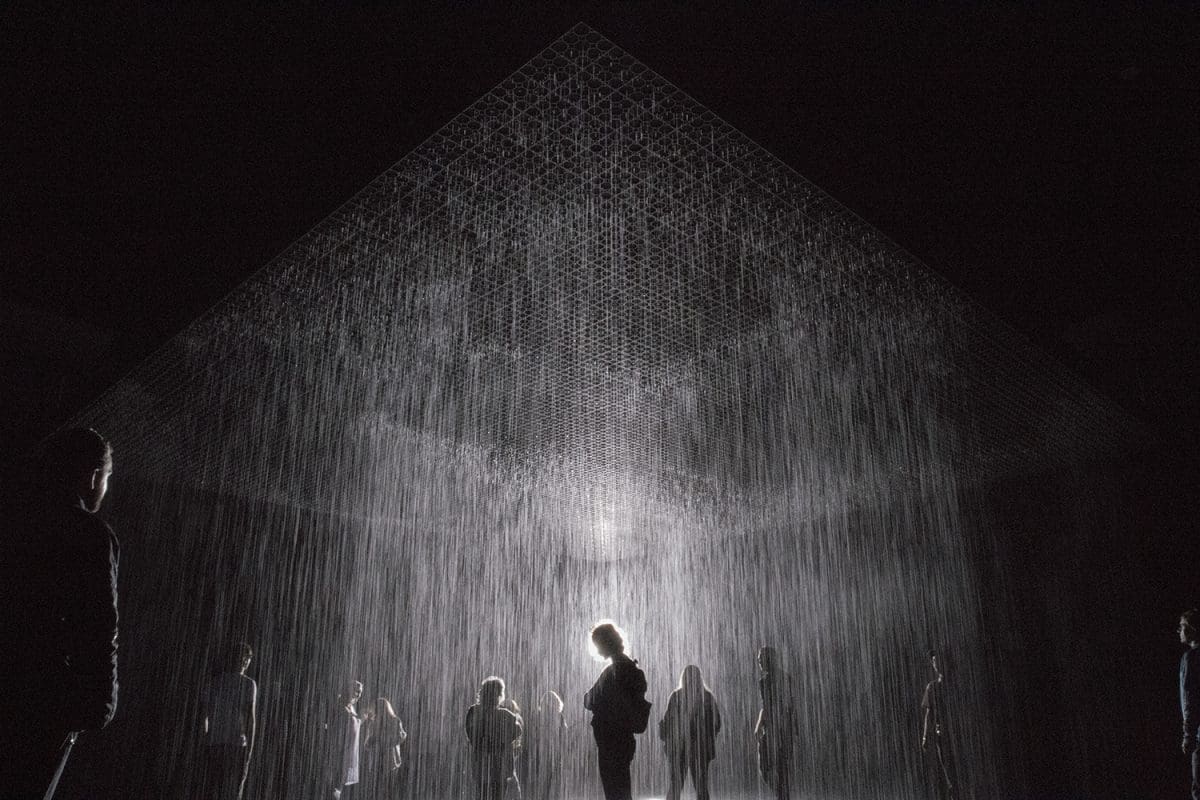

Nature as subject matter is persistent throughout the history of art. Rain Room recreates that familiar element, rain, in a controlled environment and marries it with digital tracking creating an uncanny and sublime (and very Instagrammable) experience.

The work (by the London-based art collaborative group Random International, run by Hannes Koch and Florian Ortkrass) is part of the Jackalope Art Collection owned by hotelier Louis Li. Rain Room is on view in a purpose-built pavilion in St. Kilda, Melbourne, in association with the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI).

A directional light dramatically lights a black room containing 100 square metres of continuous rainfall. A tracking device senses movement causing the rain to halt momentarily, which allows participants to walk through the work dry. They only remain dry, however, if they walk through the work slowly.

And herein lies the crux of Rain Room: the environment controls us and we control it in an uneasy symbiotic relationship.

“What is interesting is everyone sees it as rain, and it’s not actual rain: it’s a very mechanised version of it,” says Ortkrass. “But our only reference is rain, so it has to be rain.”

In its unnatural environment. Missing wind and natural shifting lighting conditions, the experience of it becomes something else; the familiar is rendered unfamiliar. In the closed-off environment the work is heavily sensorial with the look, smell and sound of falling water heightened.

The artists may be concerned with digital tracking but the work is open in meaning and uncritical. Audiences bring their own readings, whether individually specific or particular to the geographical location where it is presented.

“We were asked instantly, ‘so it’s an environmental project?’,” says Ortkrass. “We are happy for it to be shown in that context like at MOMA PS1 (New York), but it’s more about environments than the environment. A study of environments – how things feel, create this kind of mechanised world around us, and what that does to us. Because we control the rain but it actually also controls you. You have to walk at a certain pace in the work to avoid getting wet.”

Rain Room has been shown at the Barbican, London (2012); the Museum of Modern Art, New York (2013); the Yuz Foundation, Shanghai (2015); LACMA, Los Angeles (2017); and at the Sharjah Art Foundation in the United Arab Emirates (2017). This iteration is its southern hemisphere debut.

“We like to travel it, to show it in different contexts, because you always get slightly different comments and different discussions,” explains Ortkrass. The climate in which Rain Room is presented often determines these discussions.

Permanently installed in Sharjah where there is no natural rainfall Ortkrass says, “it becomes something akin to being imported. Like a kind of environmental zoo.” When the work was shown in Los Angeles, the city had not experienced rain for two seasons. “There were parents coming in with their children to wheel them around in the rain, because they hadn’t seen rain before,” says Ortkrass.

An environmental interpretation may not be the intention of Rain Room, but it is, regardless, topical and pertinent. “In the process it makes you very aware that rain is something nature does very well. To create raindrops is really hard,” says Ortkrass. “That was a research project in itself. You get really humble when you see how tricky they are to replicate.”

Rain Room

Jackalope Pavilion

Tickets essential

9 August–27 October