While manning reception years ago, I found myself explaining to an uneasy first-time gallery visitor how to get around: I suggested a route, pointed out the floor sheet, and invited them to be open to whatever feelings and opinions the exhibition provoked. I’ve never forgotten their unintentionally glib and apposite reply: “So, I go and … look? In the rooms?”

Though rudimentary, these words characterise the onus on gallery visitors to undertake engaged looking, if by ‘looking’ one means wayfinding, perceiving and experiencing. Despite the banner ‘visual art’, the eyesight part of viewership is only one layer among many. Perception of an artwork might be constituted as much by audio commentary, an insightful invigilator or movement around the gallery, as by aesthetics. For many people these off-canvas components make up the whole experience.

“If you ask people who are blind or vision-impaired if they go to galleries or museums, most say no,” says senior Queensland University of Technology (QUT) researcher Dr Janice Rieger.

“A woman born blind shared with me that at school she was told not to concern herself with visual art. Years later, she went on a gallery touch tour and a whole new world opened up to her.”

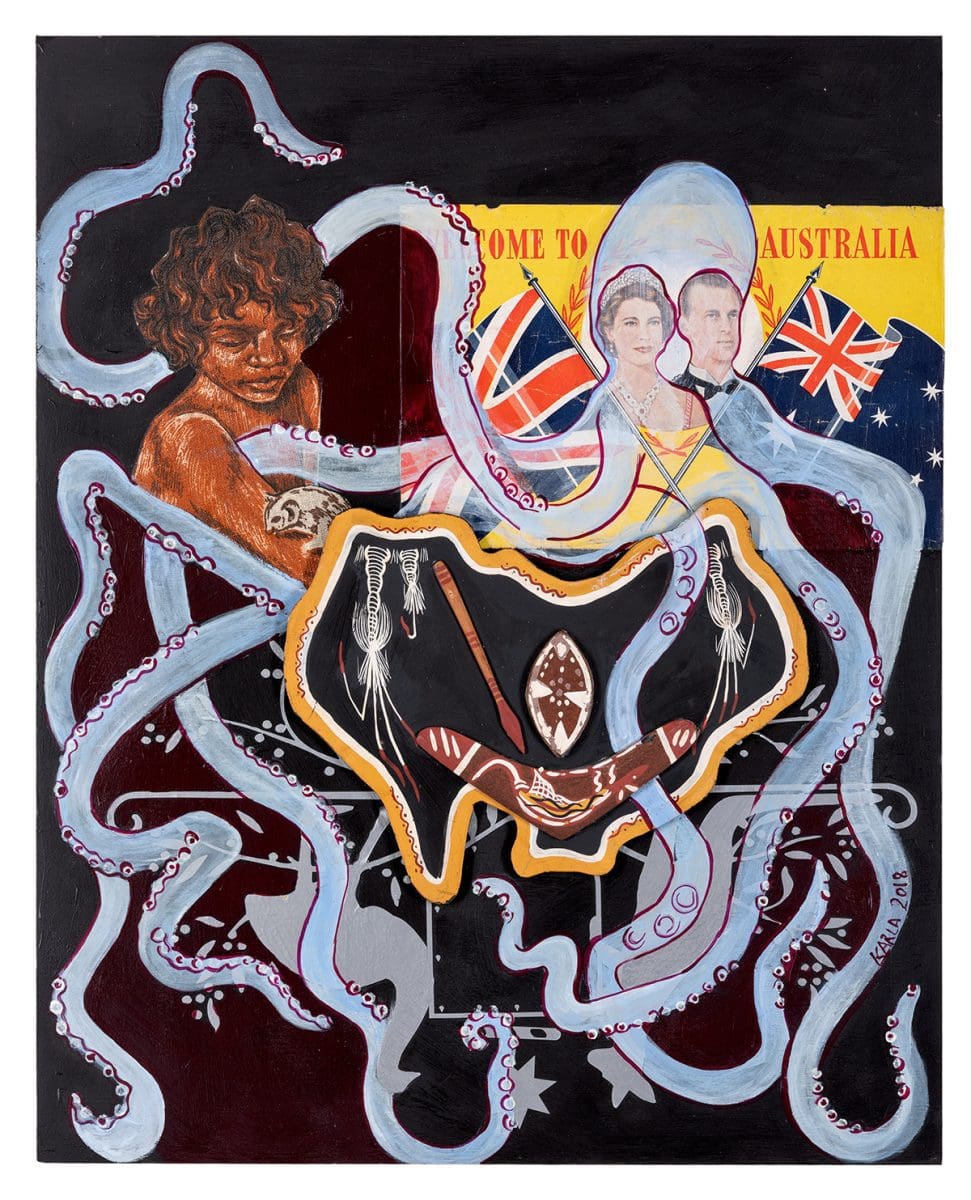

Cross-disciplinary and audience-led, Vis-Ability at the QUT Art Museum uses a selection of recently acquired works from the QUT Art Collection as a starting point from which to dethrone sight from the viewership hierarchy and facilitate a myriad of nonvisual forms of perception. Any opposition between seeing and not seeing is eschewed in favour of a more complex web of touch, sound, movement, narrative and proprioception (kinaesthetic sensing). “With 90% of the collection in storage, it seemed fitting to pair it with a discussion around access and visibility,” says curatorial assistant Katherine Dionysius.

The deployment of sensory technology in Vis-Ability has been led by expert blind and vision-impaired collaborators. “It was important not to approach this with any pre-existing assumptions or frameworks,” explains senior curator Vanessa Van Ooyen. “It had to happen through conversation.” Over a series of weekly dialogues, particular works emerged as candidates for exhibition, and were paired with representative modes like tactile images (relief versions of flat images), video simulation, touch tours and audio description.

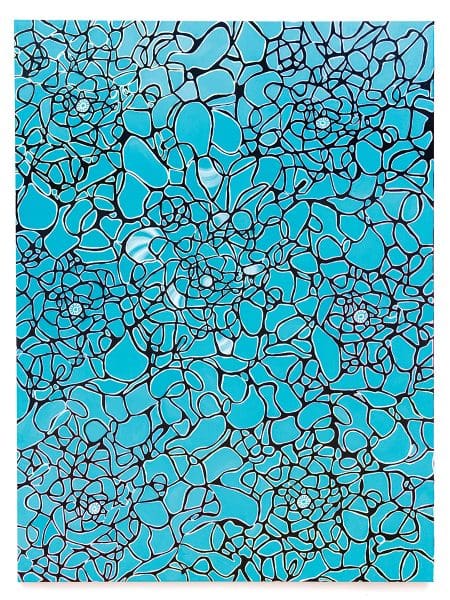

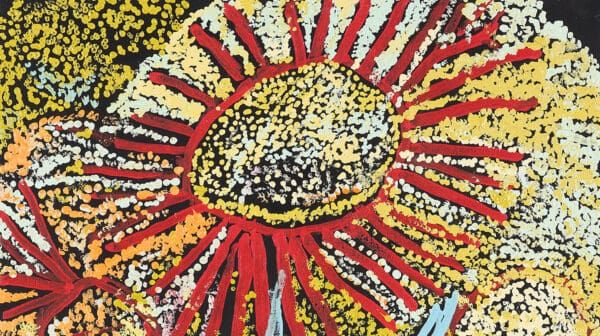

A painting by Toowoomba artist Catherine Parker is the focus of a particularly dynamic consultation process.

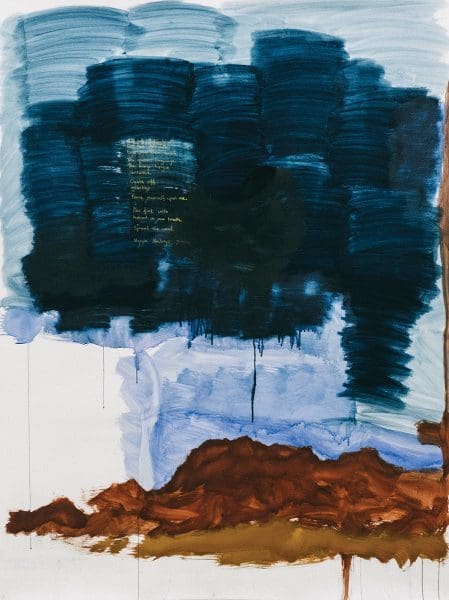

Multilayered and “difficult to describe”, Present Portal, 2017, was not on Van Ooyen’s radar for this project, “yet this surreal, complex landscape was singled out by our experts for workshopping.” Parker will meet with low vision experts and academics to co-produce a 3D iteration of her painting.

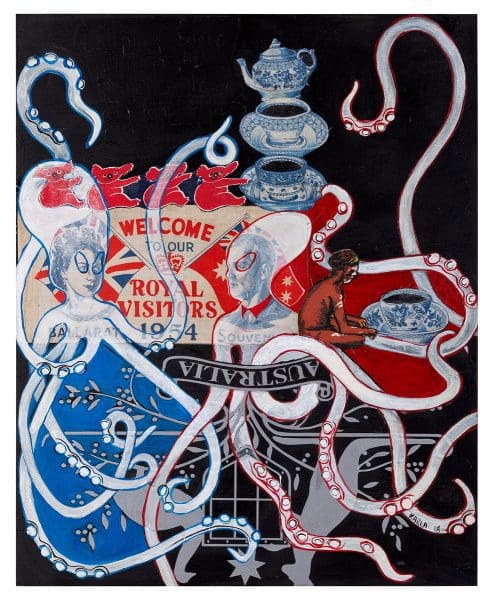

Audio description is the most prevalent technology for translating a picture into a non-visual format. Three works are extensively described in Vis-Ability, in recordings that combine expert input, curatorial writing, audio description and vocal performance. For Dionysius, this process revealed a sighted bias in the way art is commonly articulated: “I was writing about War and Peace #7, 2011, by Jon Cattapan, Lyndell Brown and Charles Green. Cattapan’s thinly-painted white lines and greenish dots are so recognisable – but it would be meaningless to describe them as ‘typical’ or ‘very Cattapan’.”

Stock adjectives like ‘purple’ or ‘bright’ are unhelpful for audiences with low vision, as are words that rely on aesthetic knowledge, like ‘impressionistic’ or ‘painterly’.

Expanding on this insight, Vis-Ability ranks its non-visual translations primary and its artworks secondary: “For some works, visitors hear the audio description first,” says Dionysius. “They understand the work through listening and imagining. Afterwards they can peer into a booth to see it.” Perhaps some sighted viewers may resist the urge to eyeball the artwork at all.

When denied the almost immediate apprehension of an image that is afforded by sight, one must engage in an altogether slower and more mindful viewership.

“There’s a concept called ‘disability time’,” Rieger expands, “which suggests that things take longer for people with disability.” Tactile images can take up to an hour to read through touch. “Vis-Ability embraces this slow temporality and what we’re seeing is that visitors are engaging with more thoroughness and purpose, a knowledge-gathering process that vision-impaired people rely on.”

In a beautifully empathetic simulation, visitors will don headphones and goggles to experience the specific visual abilities of a guest guide with retinitis pigmentosa and another with diabetic retinopathy. Each guide explains in their own words what interests them in Vis-Ability and how they perceive and connect with the artworks.

While structured around a collection survey, we might better understand Vis-Ability as an exemplar of co-design, canny use of technology and the favouring of lived experience over theory. An accessible online video-catalogue will pass on this knowledge for other institutions and practitioners. What began as a bid for inclusiveness has ripened into an immersive celebration of the remarkable, intense and unhurried practice of non-visual looking.

Vis-Ability

QUT Art Museum

11 May – 4 August

This article was originally published in the May/June 2019 print edition of Art Guide Australia.