Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

Virtual reality (VR) has been reviled as an expensive gimmick (Forbes, 2016) and endorsed as the “next logical step” by artist Jon Rafman, whose own use of mediums include Google Earth and online virtual world Second Life. Contemporary Australian artists are expanding their practices with this immersive medium too: from Joan Ross’s fraught colonial landscape, to Christian Thompson’s recreation of remote geography, Steve Dow looks at a number of artists who see VR as loaded with both hope and fear.

I am a white man who has become a white colonial woman in a yellow frock. I am standing in a warehouse in St Peters, in inner-western Sydney, otherwise known as Dr Josh Harle’s Tactical Space Lab, where virtual dreams become reality. Wearing a headset and with a control in each hand, I can see my pretty reflection in a mirror, a bonnet tied around my head. I pick up a red lipstick and apply it.

I then pick up an animated Polaroid camera in this world, snap my sweet image, and a real-life glossy photograph of virtual avatar me (in a camp pose) prints out as a souvenir to take home.

Then, having listened to British marine officer Watkin Tench’s late 18th-century Sydney diaries read over an antique telephone, I pick up a hand grenade and throw it past several cute rabbits into cascading water. I conclude I truly am a white man, destroying the land around me, albeit in colonial drag, sashaying away.

When artist Joan Ross teamed up with Harle to create her interactive game film Did you ask the river? – one of a batch of Mordant family commissioned works exploring innovative virtual reality and art, and recently premiered at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image in Melbourne – she was suspicious that virtual reality was a “gimmick”, and still nurses concerns the VR industry at its darker, artless edges might lock users into claustrophobic, schlock-horror scenarios, and encourage a narcissistic culture of the self.

“I found it really disturbing,” she says. “I thought, ‘I don’t like this VR; it’s about ‘me culture’’.” Yet this distaste led Ross to a notion that could only be executed in VR rather than her usual two-dimensional animation: to have users assent to their complicity in destruction. “We went in conceptually with the idea that people are greedy and that they will wreck the world.” Ross says some users of the work have expressed disappointment in themselves after they chose to blow up the landscape or graffiti a rock. “Most of the actions you do are a little bit destroying. You can put lipstick on, but the idea is, ‘Let’s put lipstick on while the world burns.’”

Harle recalls one elderly female user telling him that the avatar should be a man. “She said, ‘A woman would never have done those things’,” he says. “The funny thing is ‘these things’ she’s talking about are the things she’s just decided to do. Some people were more graciously accepting of what had come to them than others, but a handful of people felt tricked into being caught out.”

Apart from making elegantly executed arguments about colonisation, where are artists heading with virtual reality? London-based Australian artist Shaun Gladwell has co-curated VR symposia at film festivals. As part of the BADFAITH collective of six artists last year, he helped create a 12-minute VR film, Exquisite Corpse, based on a surrealist parlour game, with each artist assigned a certain body part kept secret from the other contributors, their films then stitched together.

Experience taught Gladwell that the running time was too long. “People are finding it hard to stay in longer format material, we see the rise of this thing in VR, the five-minute epic, which means you try to blow people away in five minutes or thereabouts.”

For his upcoming career survey Pacific Undertow at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney, Gladwell will premiere a new solo VR work, Electric Monuments, which again delves into the user’s sense of their body within the virtual reality world. Nonetheless, Gladwell is cautious that virtual reality can be both a cause and cure for bad faith, as the line between genuine and inauthentic experience blurs.

“There will just be that period where a susceptibility or gullibility towards an experience can also somehow delude you,” he says. “It has the power to be an incredible educational tool, but it also has a darker side as well. In terms of propaganda, it’s an incredibly manipulative tool. The brain gets tricked for the first experiences in VR because there’s no end to the peripheral vision within the new space. Optically, it’s a completely embodied 360-degree illusion. You can also have volumetric and interactive experiences in VR.”

Universities are already trialling what Gladwell dubs the ‘metaverse’, where two people in different physical locations can make a time to meet in virtual space together. “[As yet] you can’t actually see someone’s body, although that’s all changing as well. You can have live cam views and all sorts of stuff.”

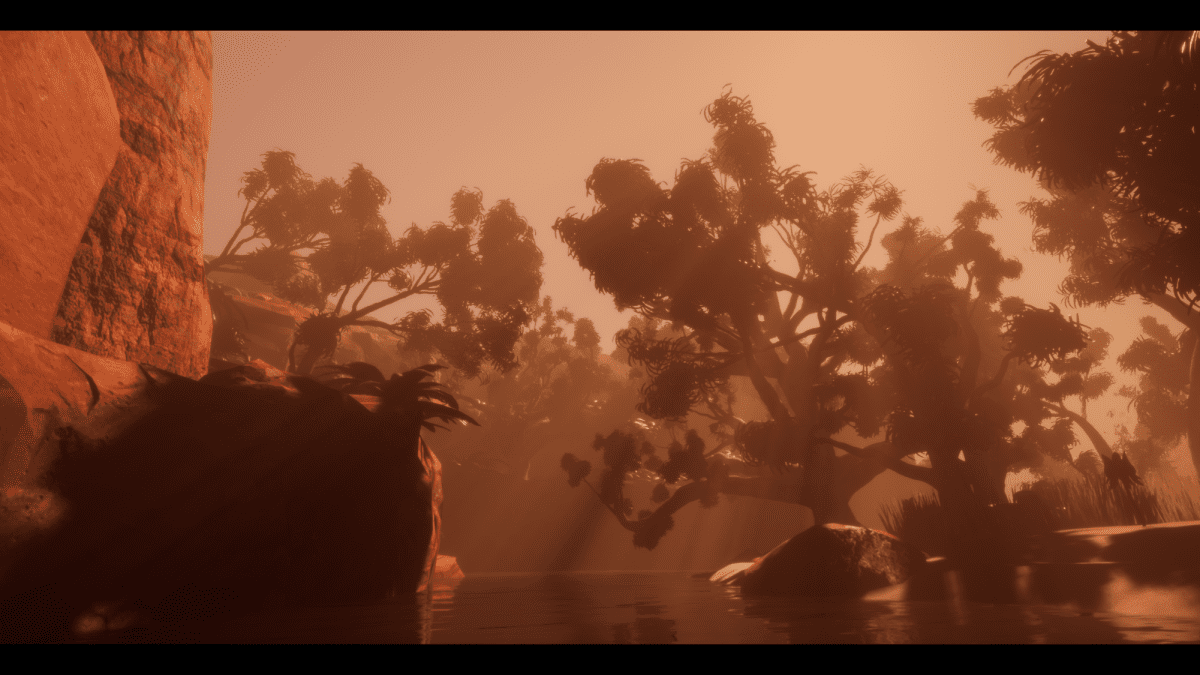

I am happily alone, having a spiritual experience. Standing on a circle of sand to stay within virtual reality range, I hear artist Christian Thompson singing in Bidjara, an Australian Indigenous language his father spoke before learning English. I see a 360-degree landscape filmed on location at Six Mile Creek in central western Queensland where Thompson swam as a child, amalgamated with the broader geography of Springsure, Charleville and the Carnarvon Gorge, where his people are from. I see what appear to be hot embers, and my mind tricks me into feeling heat; when the rain comes, I feel a chill.

Thompson tells me this work, Bayi Gardiya, which translates as singing desert, was a natural progression from his two-dimensional, three-channel screen work Berceuse (French for ‘lullaby’) from his firstever survey, Ritual Intimacy, at Monash University Museum of Art in 2017, in which he also sang in Bidjara. He worked with more than 15 people on Bayi Gardiya, a much larger team than he was used to, with an illustrator storyboarding his ideas.

Location shooting took four days and seemed analogue on the surface – “stepping a metre, taking three photos; walking another metre and grabbing another three photos, mapping it out in that way; we also did aerial footage with drones” – yet the whole film took a year to complete, beginning with the complex sound work.

In singing in Bidjara, with a vocabulary he has been building up since 1995, his first year in art school, Thompson says it’s no longer possible to consider the language lost. Virtual reality may be complex, but in one sense becomes importantly practical: “I’m using the art context as a site to archive our language in a way that’s contemporary, dynamic, hopeful, aspirational,” he says; “it’s not relegated to the realms of ethnography or anthropology.”

The intricate work also combines Thompson’s memories of taking a dip in the water with the ecological reality that the river has run dry, and users come to understand that language and landscape are linked. “It’s 13 hours inland from Toowoomba; it’s a long way away, so I kind of wanted to collapse that space between remote and metropolitan experiences and allow people to have an experience here who might not necessarily be able to get to central Queensland.”

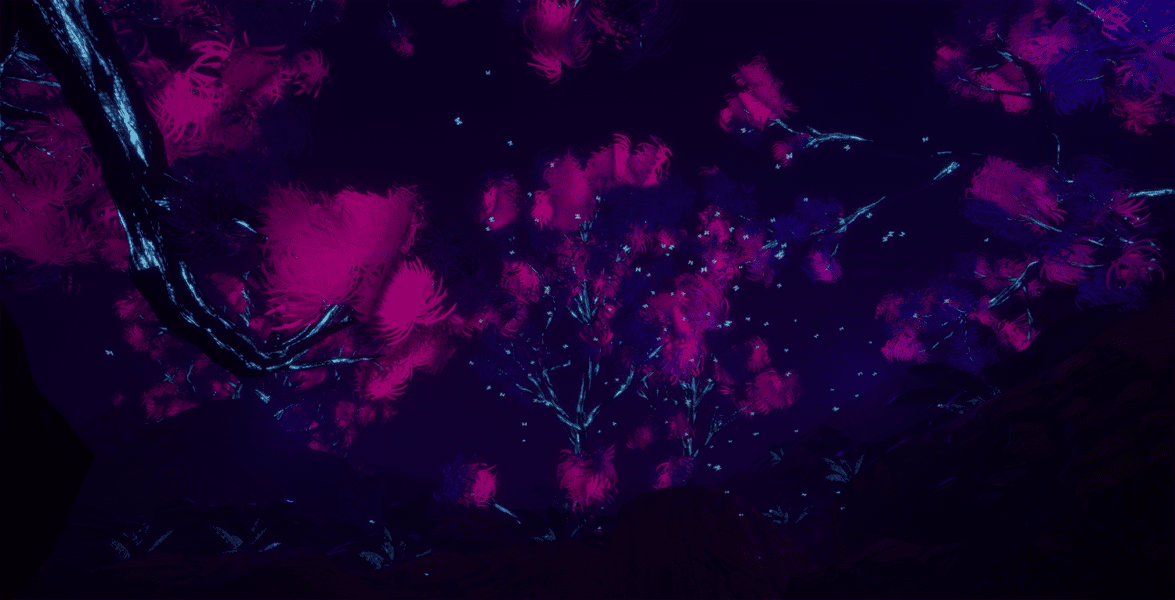

Collapsing an even greater sense of geographical distance is Australian virtual reality pioneer Lynette Wallworth. Her film Collisions, which helped viewers understand the view of elder Nyarri Nyarri Morgan of the Martu people in Australia’s Western Desert, prompted a chief of the Amazonian Yawanawa people, Tashka, to invite Wallworth to make her latest film, Awavena, among his people. Her next film will be on nomadic people in Mongolia.

Wallworth says virtual reality is compatible with Indigenous thinking: in Awavena, for example, she shows the transcendent visions of a woman who defied gender norms to become a shaman. “Virtual reality suited a state of being,” says Wallworth, who is careful to allow the First Nations VR subjects to examine the film and sound equipment and ensure she does not transmit culturally sensitive information. “What other technology would allow you to perceive the world differently according to the viewpoint of someone who is in an altered state, whose fundamental request to me was that technology show you, one, that the forest is aware of you, and two, that everything is alive?”

Awavena required three canoe loads of equipment. Virtual reality can be time consuming, much more than a comparable 17-minute two-dimensional film, “because you’re wrangling so much data and working with interactivity,” says Wallworth. “If you can imagine, I’ve got 16 cameras; eight pairs of stereo cameras, and I might need to remove something from one of the frames, so that means removing four cameras or six cameras at the back. Your range of what you’re able to manoeuvre is extreme and you need far more time in post-production than you would expect.”

Wallworth advises novice virtual reality film makers to pay attention to ‘spatialised’ sound – directional as well as lapel microphones to help guide the viewer.

The virtual future is potentially utopic in the right hands. “At the moment we are recalling the experience of VR in the part of the brain where we might recall a dream,” says Wallworth, who hopes social spaces will one day allow subjects to meet viewers in real time: “I would love them to be present when people experience their story, without them having to leave where they are.”

Shaun Gladwell: Pacific Undertow opens at Museum of Contemporary Art Sydney, 19 July—7 October 2019.

Shaun Gladwell is represented by Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne.

This article was originally published in the July/August 2019 print edition of Art Guide Australia.