For almost 40 years, Keerray Woorroong Gunditjmara woman Vicki Couzens has worked in the Aboriginal community, profoundly changing the cultural landscape around her.

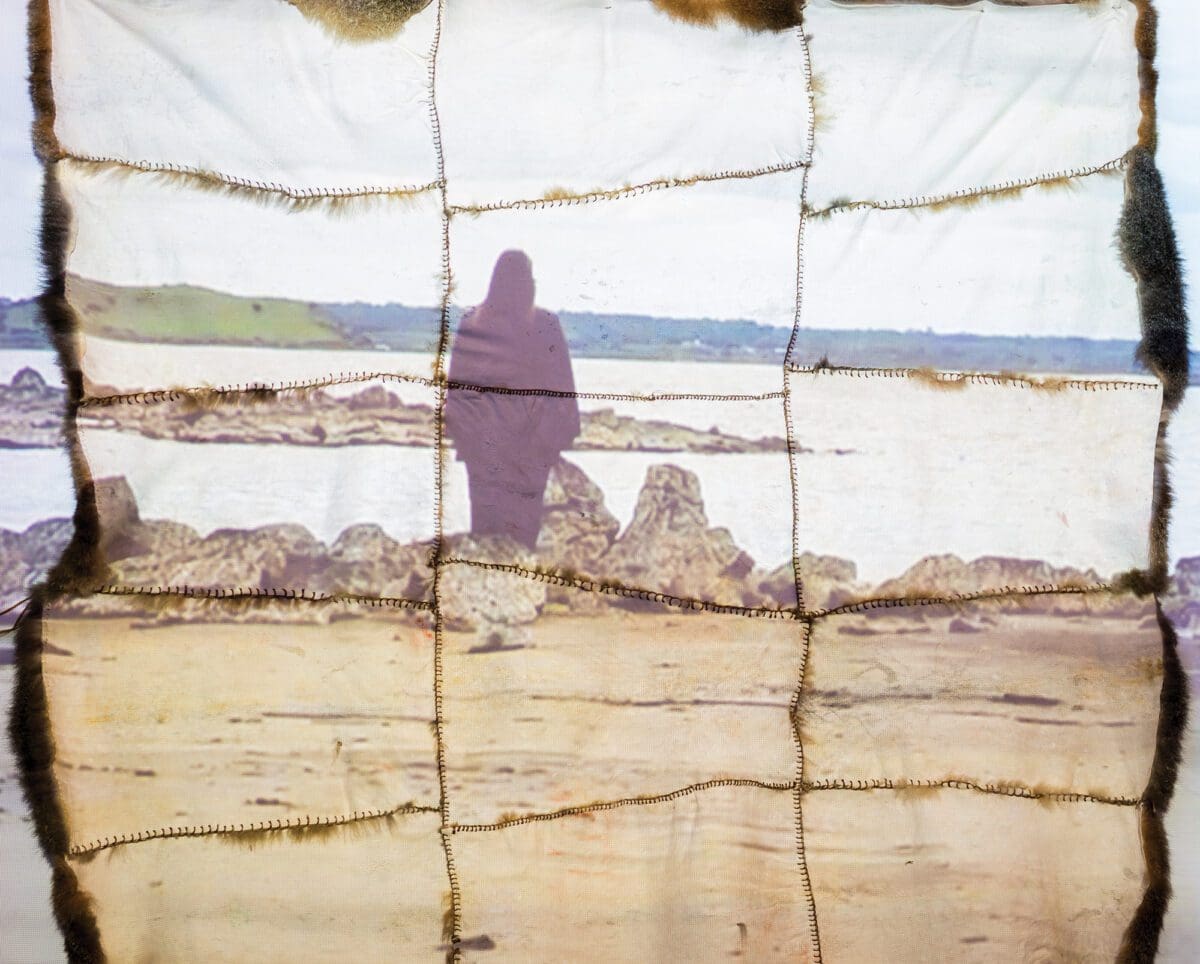

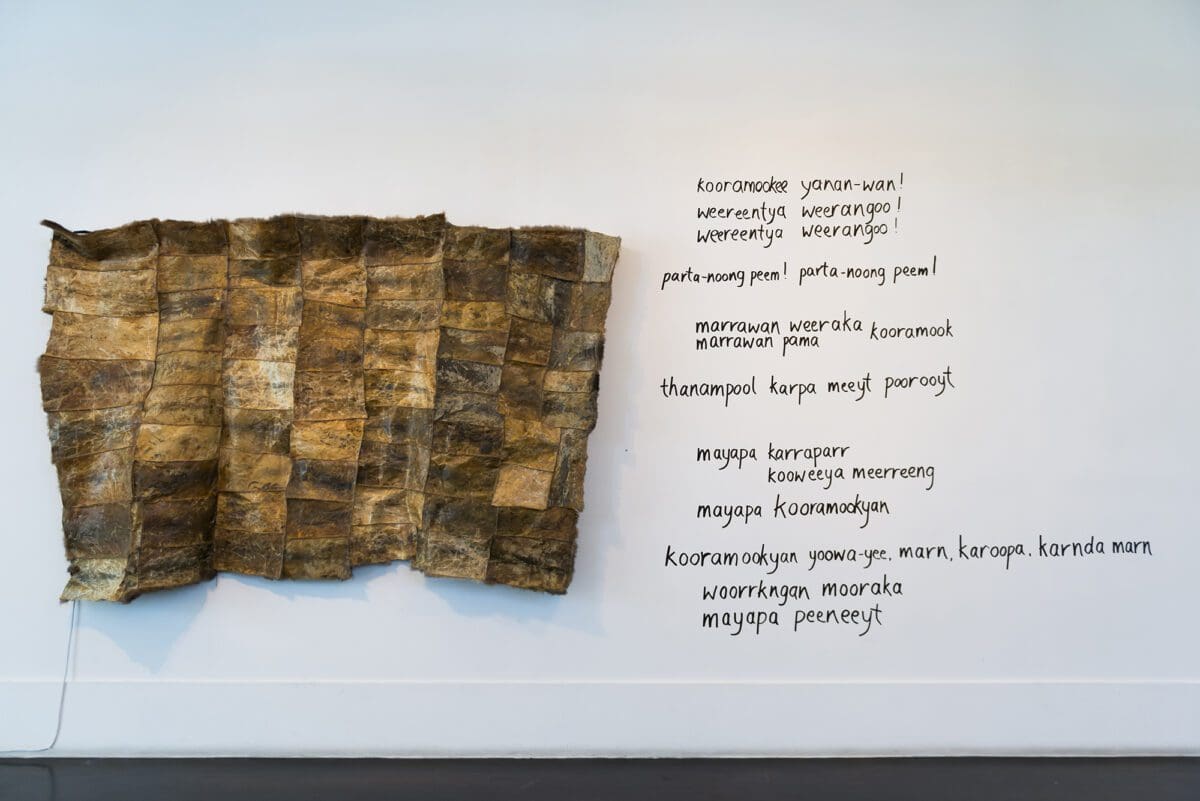

In 1999, Couzens attended a workshop at Melbourne Museum and encountered the Lake Condah possum skin cloak. After this experience, and along with others, Couzens set about revitalising the practice of creating the cloaks, culminating in their appearance at the 2006 Commonwealth Games opening ceremony—and being exhibited at galleries Australia-wide. It’s just one example of how Couzens reclaims Aboriginal cultural practices and knowledges.

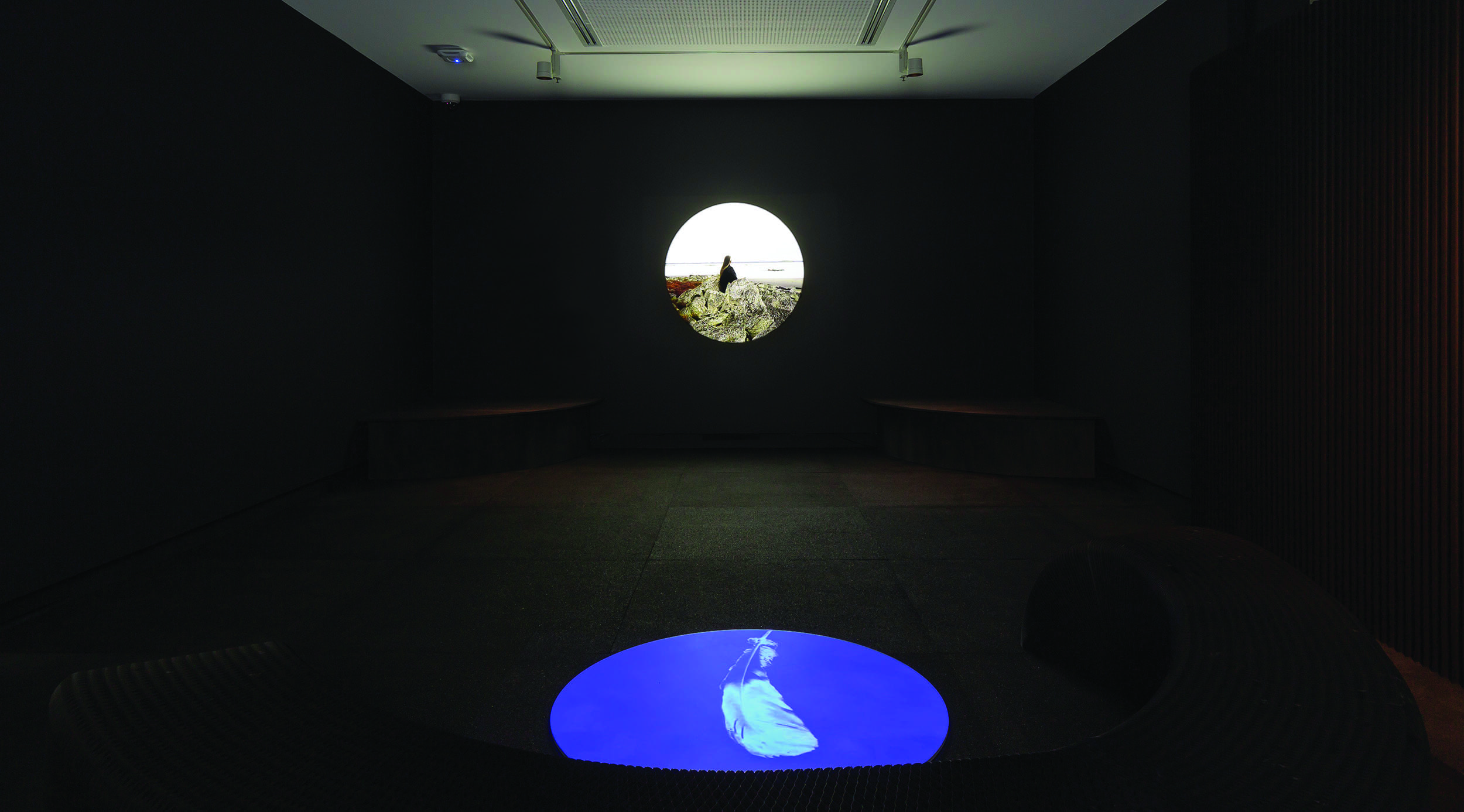

Couzens has sat on various organisation boards, is undertaking a PhD in language revitalisation, and also creates “artworks”—although this term is contested in our interview. Ahead of Couzens’s sound and image installation for nightshifts at Buxton Contemporary, created with Robert Bundle, we talk about lifelong learning, the importance of listening, and what propels Couzens’s tireless work in creating moments of knowledge sharing.

“I do create artworks like paintings and printmaking, and even public art, but it’s the purpose, intent and the story that is behind the artworks or the creative expression.”

Tiarney Miekus: I know that your preferred description of your practice is “creative cultural expression” rather than “artist”. Can you unpack why that’s a better fit?

Vicki Couzens: Creative cultural expression covers the spectrum of what I do, and it’s more accurate in terms of what the definition of “artist” might put in people’s minds. Like, “Oh, that’s a person who makes art and is part of the art world.” Which is a Western construct anyway, in terms of fine art and galleries, and the way that world works. I don’t feel connected to that. If I’m in galleries exhibiting, that’s great, but it’s not my goal. I get invited to do those things and sometimes it has been my goal to be in exhibitions because part of what you’re doing is sharing the story; a form of activism in terms of assertion of our presence by telling our stories and sharing them in those places, and therefore educating mainstream.

I do create artworks like paintings and printmaking, and even public art, but it’s the purpose, intent and the story that is behind the artworks or the creative expression. In our culture—story, painting, song, dance, they’re all part of the same story and one can’t be without the other. Even though you might see a painting and you’ve got a little label and a story, it’s only part of the expression of that story. It’s also a form of documenting for the future and ways of sharing.

Of course, while I’m not into the fine art world, we all make work for the market, which is nothing new. We had our own economy prior to colonisation with trade, including things that we would make, and now is no different in some respects. For example, in the early colonisation period, in the Gold Rush, people were advised to employ a black tracker and buy a possum skin cloak, so you didn’t freeze in the Goldfields. We were making them and selling them to the market.

There’s also the underpinning of reclamation and revitalisation of our knowledges and practices. Nothing in our culture is siloed to a department or sector: art is part of life. Creative expression is a better way to describe how people interact with the world. It’s that immersed, embodied experience.

TM: That reminds me of something you once said on creating: “Art is about working in a community rather than just making a pretty picture.” While I find much of your work visually profound, I wondered if that sense of art being community led was happening before you even made what can be called “artworks”?

VC: That’s a good question to make me think of it that way, because before I became an artist—or before people started calling me that—in the early 80s in Geelong, I ran a screen-printing project. I got the community in and I thought, “Oh, I’ll just have a little dabble myself.” Not considering that I might be an artist, I was just having a go. So that community project happened to be a creative project.

Another one was, we used to drive around and pick up lots of kids out of school one afternoon a week, and we would do cultural things, whether it’s singing contemporary songs, learning a bit of language if we could, talking about sites, or we’d have an afternoon tea for Elders and the kids would get to interact with the Elders. That is creative expression as well.

But if I’m doing a public artwork, for instance, you have this responsibility to be representing not just yourself, but all those who’ve come before: your ancestors and that body of knowledge that you are working from. Most stories I tell aren’t mine alone. They might be a family story that’s part of a larger collective of knowledge. I’m very conscious and respectful, and acknowledge that what I know is part of a much larger thing.

“Normally cloaks are about you, your family and your clan, and they’re used from everyday things to keeping babies warm to ceremony, and being buried in them.”

TM: Going back in time, I know that your father was a huge mentor and inspiration for you, particularly his involvement in revival languages. And that you were born Warrnambool, living on Country, and then relocated to Geelong in the early 70s, and that learning of your matrilineal history, particularly your grandmother’s story, was very important for you. What was that upbringing and learning like?

VC: Learning is a lifelong thing. We were born into community, family and culture—but traditional dance, for instance, no, we didn’t do it. We revitalised and learned that, and brought that back. That is how it is in this time, where some of those practices have been left sleeping because of the colonial, oppressive systems that have interrupted our practices.

Making possum cloaks, for example, was a vision gifted to me from the old people who made the Lake Condah possum skin cloak. Two of my great-grandfathers were makers on that cloak, which I didn’t know at the time [when first encountered the cloak], but the oral history was handed onto me from two of my Country women from that side of Gunditjmara country, my grandmother’s Country. That knowledge around making cloaks was something that had been interrupted and was not a common community practice anymore—but it is now.

In that encounter I had at the museum [a workshop in 1999 at Melbourne Museum], the old people came, and I had this experience, and they gifted this mandate to bring the cloak back to community. That’s what I set about doing with other people. It was really 2006 with the Commonwealth Games [where the cloaks featured in the opening ceremony] that enabled us to bring that back into practice. It’s become iconic with the southeast of Australia. It’s an identity marker, a collective one. That’s creative cultural expression. It’s not art; even though we exhibit them, and people are doing really creative things with them.

Normally cloaks are about you, your family and your clan, and they’re used from everyday things to keeping babies warm to ceremony, and being buried in them.

But now, people make them to tell a story about food and plants, or a particular site. They’ve become these vessels and repositories of knowledge in a contemporary sense. People have even been using them as evidence in their Native Title claims. This has seeded the need to know more about what’s our language for possums? How did we use them in ceremony? Who made them? What stories? Where do you get the ochre? These seeds ripple out into furthering that revitalisation.

As an example in my own personal experience, I knew that my nan used to basket weave. But we were busy growing up and playing sport—and nan passed when I was 10—so we didn’t go basket weaving. Then in Gippsland, when I was around 30, I was working with the TAFE and we started doing basket weaving with the high school students. Auntie Linda Turner taught us all and I came home very proudly with my first basket, a bit dodgy, but I thought it was wonderful. And I showed my dad, and he’s like, “Oh, that’s cool.” And he stuck it on his head because dad was a joker. But then he started telling me how much he used to help his mum weave, and I didn’t even know that until I had a basket right there. Sometimes if you don’t have the circumstance this knowledge doesn’t get handed on.

TM: So much of your work is about creating that circumstance, whether it’s in a gallery, your PhD on language revitalisation, or so many other projects—you’ve always centered knowledge sharing. Is that something you’ve consciously made your life’s work? Or it’s intuitive?

VC: A bit of both because it’s the default setting! My husband and I have talked about this, and sometimes we go, “Why are we doing this? Why do we keep trying to share or educate or teach or learn, or share learning?” It’s our default setting; intuitive and deliberate at the same time. I’m also more able to talk about it because people ask me about it now, whereas I just used to do it.

But we work in that community and collaborative way. Some collaborations are fairly quick, like, “I’ve got a deadline so come and help me finish this artwork!” And then there’s collaboration of creating space for where community come in. Like the possum workshops, but language and weaving are similar. People come in and they connect to the knowledge and the practice of weaving, and sewing the cloaks. And they’re not artists. Like how I started out, I was just someone who could make things happen.

We’ve seeded lots of things. We’ll start something and then it grows, whether it’s an artwork or a playgroup for the mums. Like when I was young and having my babies, there was no playgroup. So, I set one up and ran it, and then the organisation ended up getting resourced to run itself.

Those ways are somewhat inherent in my being and there’s the creative thinking on how to create opportunities and make things happen. I see my role on boards and committees as creative because although there’s the boring paperwork, it’s about how can you grow your organisation to respond and fit the community, not the other way around? It has to be collaborative.

TM: In learning about your life and work, I thought so many times, “This person really makes things happen.” Not only your work in the community, but you’ve also raised five daughters and now have grandchildren. And I can see how busy you are even right now—do you ever get exhausted, or does the work give you energy?

VC: We get exhausted, we run out of steam. At one stage in the late 80s we moved from Geelong to Gippsland, and I was done. I said, “I’m not working in our community anymore.” I went out to the bush and didn’t talk to anyone for a couple of years. I took the kids to school and things like that, but stayed away from community. We just had massive, major political disappointments. But, in the end, I couldn’t stay away.

When I met my husband and started having babies, that also flipped the switch. I mean, before having babies I was already on the board of directors at Geelong [Art Gallery] and looking to those kinds of roles, but having kids flipped the switch in terms of responsibility. And I think from my dad and mum, making the world a better place underpins all those things.

“Deep listening is about using all your senses, not just your eyes, ears and smell, but the extra sensory.”

TM: To talk about your current work at Buxton Contemporary, it’s a new sound and projection installation created with Robert Bundle that draws on the Indigenous concept of deep listening. Can you talk about that concept?

VC: Deep listening is a phrase coined by Miriam Rose Ungunmerr Baumann from the Daly River mob in the Northern Territory. She talked about deep listening as an Aboriginal way of being, and understanding and connecting to the world, and belonging in the world. It’s really caught on, and it’s a good thing for mainstream to be understanding, because it’s that whole ontological sense of being in the world. It’s even the understanding of the first sound, the first light, from creation.

People talk about “Oh, we’ve been here 60,000 years.” No, we’ve been here since the beginning, from creation. But Rob did most of the work in creating it because we’ve got so much sound and image recorded that we’ve drawn on our archive from previous projects, and put them together. We’ve got sounds of the earth, space sounds, crickets and water running. We’ve got seating in the space; it’s a dark, immersive space, almost cocoonlike so it’s a sensory experience of visual and audio. Rob also came up with the idea that some of the seats have subwoofers; you can physically feel the sounds.

We’re trying to evoke that sensory experience. Deep listening is about using all your senses, not just your eyes, ears and smell, but the extra sensory. Like you mentioned intuition before, not a lot of people follow their gut feeling. But that’s where knowing comes from, that intuition, being guided through that sense.

TM: I’m probably taking this beyond the work, but you look at the news and these constant conversations on the left and right of politics, and people aren’t listening to each other; it’s like a refusal. Was that something you were thinking about?

VC: Well, yes—but that’s a Rob thing. He thinks in the bigger. Like, I think in the big picture, but he thinks in that even bigger, bigger picture. Definitely the political and getting people to understand connectivity and interconnectedness. There is no separation. The consequence of not listening to each other is really destructive.

TM: Can you ever persuade people to listen?

VC: You can only offer the opportunity. It’s that old saying of leading the horse to water. With our [nightshifts] work, with the sound and light, it’s about frequency and vibration, because everything is frequency and vibration. How you be in the world impacts and contributes to that. But yes, it’s incremental and it’s slow sometimes.

nightshifts

Buxton Contemporary (Melbourne VIC)

On now—29 October

This article was originally published in the July/August 2023 print edition of Art Guide Australia.