Life Cycles with Betty Kuntiwa Pumani

The paintings of Betty Kuntiwa Pumani form a part of a larger, living archive on Antaṟa, her mother’s Country. More than maps, they speak to ancestral songlines, place and ceremony.

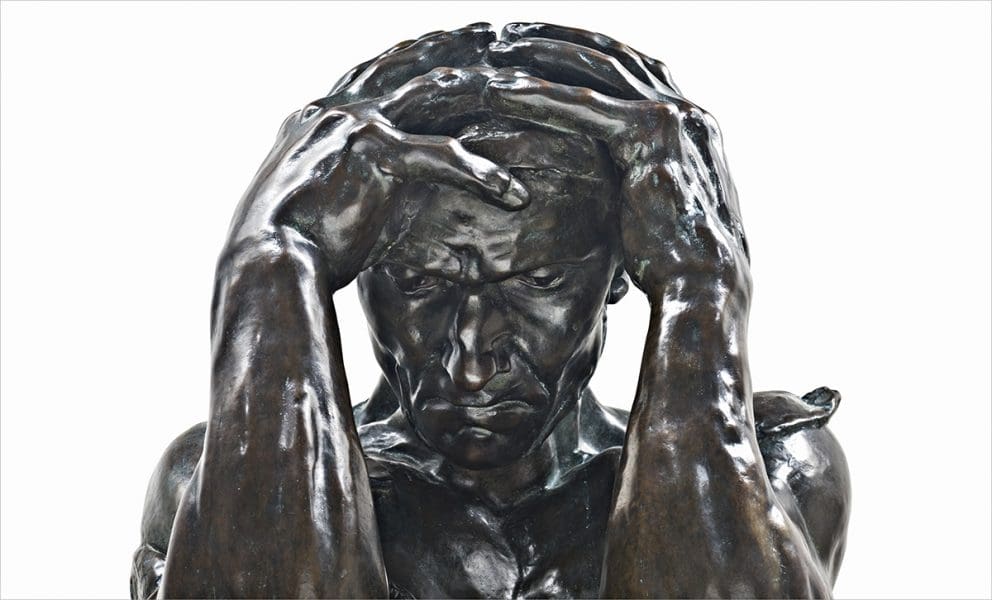

Auguste Rodin, France, 1840-1917, Andrieu d’Andres, monumental, 1886 (Coubertin Foundry, cast 1989), Paris bronze. William Bowmore AO OBE Collection. Gift of the South Australian Government, assisted by the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 1996 Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide.

Rosemary Laing, Australia, born 1959, a dozen useless actions for grieving blondes #2, 2009, Sydney, type C photograph, Gift of anonymous donors through the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 2016. Donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide. Courtesy the artist and Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne.

Auguste Rodin, France, 1840-1917, The Walking Man, large torso, after 1887 (E. Godard Foundry, cast 1985), Paris, bronze, 110.0 x 68.0 x 38.0 cm. William Bowmore AO OBE Collection. Gift of the South Australian Government, assisted by the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 1996 Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide.

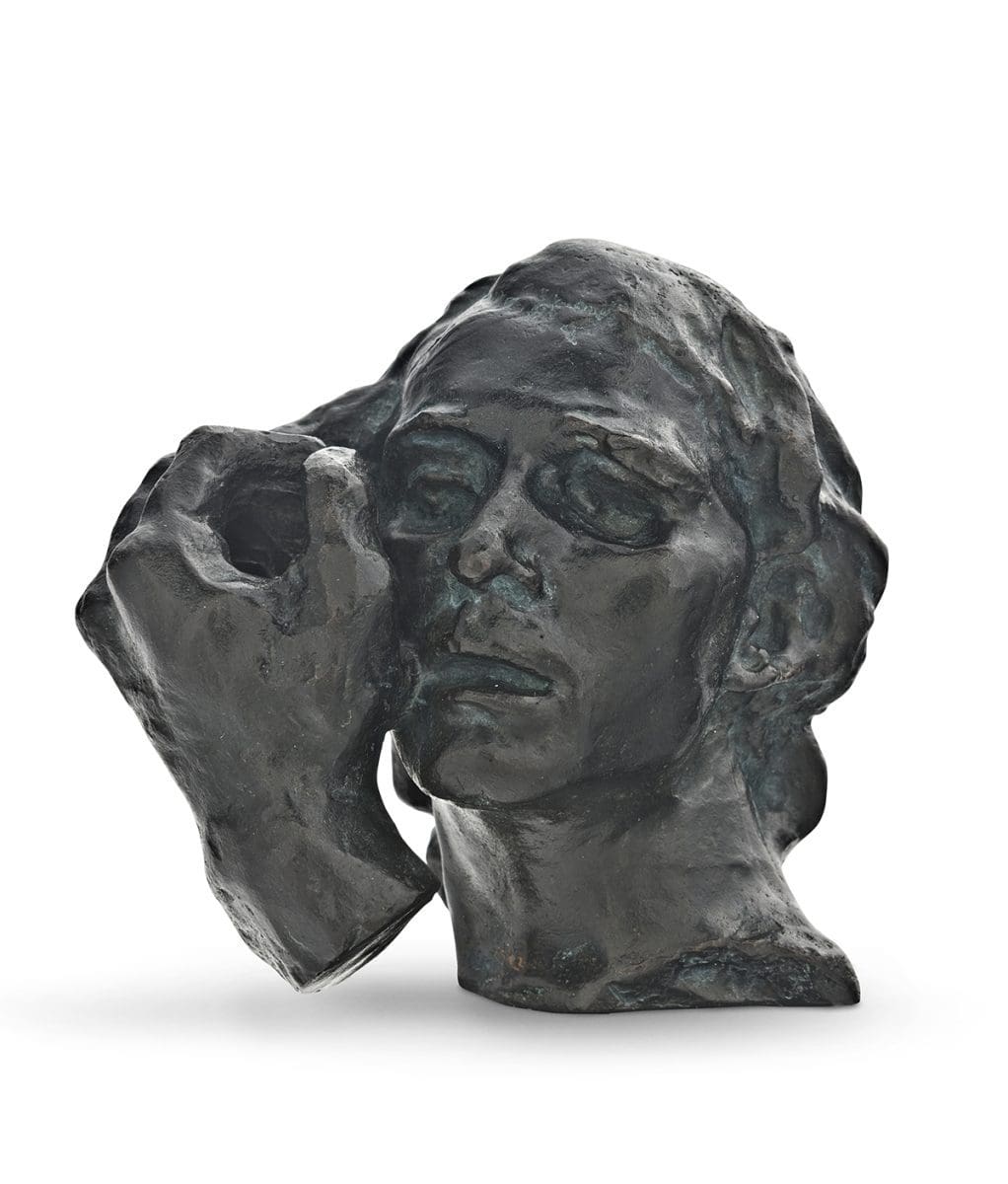

Auguste Rodin, France, 1840-1917, Jean de Fiennes, head of the reduction, with left hand, c.1885 (G Rudier Foundry, cast 1985), Paris, bronze, 8.0 x 8.3 x 7.0 cm. William Bowmore AO OBE Collection. Gift of the South Australian Government, assisted by the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 1996. Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide.

Frank Auerbach, Britain, born 1931, Head of Helen Gillespie III, 1965, Camden Town, London, oil on canvas on board, 74.9 x 61.0 cm. Gift of the Contemporary Art Society, London 1969. Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide © Frank Auerbach, courtesy Marlborough Fine Art, London.

This year marks a century since the death of Auguste Rodin. Widely regarded as the father of modern sculpture, his work was emblematic of a growing focus on experimentation and process, and a disregard for the establishment. Leigh Robb, curator of Versus Rodin, views this anniversary as “a meaningful reason to review the legacy of Rodin and bring it into a very contemporary context.”

Far more than a mere retrospective, Robb has conceived an ambitious and far-reaching trans-historical exhibition across modern and contemporary practice, bringing together a wealth of artists.

”Rodin’s ideas of the fragmented body have irrevocably changed art and figuration,” she explains. “He was really a proto-contemporary artist – even in the way he ran his studio, employment of models, and the posthumous agreement around Musée Rodin.”

This last included directions for the casting of previously unseen sculptures in bronze editions of 12, exponentially expanding their potential audience. It’s easy to see how this paved the way for the kind of large- scale studio production that is now commonplace.

“[Rodin] imagined how his work could be seen in every gallery around the world,” Robb says. “It was very forward thinking; no one else at the time was doing anything like this.”

With the sculptures as anchor points, the galleries progress through examinations of the body in different contexts: as classical, fragmented, social, erotic, emotional, ‘mind- body’, and contemporary.

Throughout, Rodin’s works form dialogues – “duels and duets”, as Robb calls them – with the art of over 60 artists. These are drawn largely from the state collection, as well as loaned pieces, and include Louise Bourgeois, Sarah Lucas, Kara Walker, Francis Bacon, William Kentridge, Chris Ofili, and Emily Kame Kngwarreye – to select but a few. The pairings are sometimes formal, sometimes conceptual; often unexpected, always striking. Many works have never been exhibited in Australia before, and include six new commissions by Australian artists.

One intriguing inclusion of lesser-known Rodin works is a series of lithographs, produced from watercolour drawings to illustrate Octave Mirbeau’s 1902 novel The Torture Garden. These gentle sepia washes nevertheless describe the body under extreme duress. Shown alongside works by Mike Parr, Brent Harris and Kiki Smith, this section of the exhibition examines the ‘emotional body’ in its many forms.

A major piece exploring the ‘fragmented body’ is Xu Zhen’s immense work Eternity, 2013–14. Shown at the 2016 Sydney Biennale, it will be seen for the first time in South Australia. The installation is composed of a row of headless deities from the Parthenon’s east pediment; blossoming from their necks are inverted bodies of the Buddha, replicas of ancient Chinese sculpture.

Robb describes the exhibition as “populated by a multiplicity of bodies”, and among the commissions are two dance works to bring real-time movement into the gallery. Australian Dance Theatre has devised a new piece for multiple dancers, Objekt, 2016, which further explores the exhibition’s preoccupation with doppelgängers and doubles; this will be performed several times throughout the exhibition. Another work, by local artist Bridget Currie, is a more intimate affair for a solo performer – the artist’s sister, dancer and choreographer Alison Currie.

Crucially, Versus Rodin embraces many different bodies and different voices. The white, conventionally beautiful, heteronormative body is opened up to a wealth of possibilities: a body that is queer, transitioning, non-binary; a body of colour; a body that is incarcerated, disabled, even futuristic. It’s a timely interrogation of Rodin’s legacy, expanding it into the present moment.

Versus Rodin: Bodies Across Time and Space

Art Gallery of South Australia

4 March – 2 July