Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

In 1967, the year artist Vernon Ah Kee was born in the small town of Innisfail, south of Cairns in Far North Queensland, Australians voted to change the Constitution, amending two sections that discriminated against Indigenous people.

In 1971, a Census was held that counted Ah Kee and his family for the first time.

Fifty years after the Commonwealth began making laws for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, constitutional recognition of the first Australians is yet to be achieved. Indigenous incarceration rates are 13 times higher than for other Australians. Life expectancy is about a decade shorter.

Ah Kee’s show at Sydney’s National Art School, Not an Animal or a Plant, investigates race, ideology and politics and commemorates the 50th anniversary of the referendum, which occurs in May.

The artist suffered a heart attack late last year. He nearly died, says his Brisbane-based gallerist. “I’ve been out of hospital one week,” Ah Kee confirmed in an Art Guide interview in November 2016. “I am very determinedly trying to take it easy, which is not as easy as it might sound.”

Due to his ill health, the show is now more of a retrospective, but there will be some new work: huge charcoal drawings of lynched bodies referencing both the colonial legacy of slavery in the United States and historical treatment of Indigenous Australians.

I tell Ah Kee that we are the same age, both turning 50 in 2017. “You had been born into citizenship,” he remarks, noting he was aged four before he was counted in the Census. “I had been born a non-person.”

How unquestioned does white normativity remain? “Well, we know how normalised Australia’s brand of racism is, when we see rules and laws made around Aborigines and no one cares. And the fact Australia can find some justification, and indeed goodness, in its treatment of refugees, should be baffling to everybody. But it isn’t.”

Spending his boyhood in Innisfail and teenage years in Cairns, Ah Kee, a member of the Kuku Yalanji, Waanji, Yidinji and Gugu Yimithirr peoples, would spend hours drawing in his room.

His father, Merv, who died in a car accident in 2014, was, along with his mother, Margaret, a passionate advocate of Indigenous rights and education. They had five children.

“Certainly, my family was [politically] awake, so to speak, and not just my nuclear family. I’ve got hundreds of cousins.”

In 1968, conservative Queensland premier, Joh Bjelke-Petersen who earned the moniker ‘the Hillbilly Dictator’, was sworn in. “Queensland is still very much in the clutches of the Bjelke-Petersen era. I only know in hindsight that my life was extremely repressed. All the Aboriginal families around me, we were all suffering the same levels of abject poverty. As anything, you find your own happiness within that context.”

The writings of Malcolm X and James Baldwin influenced Ah Kee – “beautiful articulations for the civil rights movement” – as did the late Wiradjuri and Kamilaroi activist, artist, poet, playwright and printmaker Kevin Gilbert: “I think Kevin Gilbert is one of the heroes of the Australian Aborigine in modern times, but very much unheralded, almost deliberately so.”

A member of the Brisbane-based proppaNOW artists’ collective, Ah Kee completed a Bachelor of Visual Arts at the Queensland College of Art at Griffith University. The text art of US artist Barbara Kruger was a primary influence – “feeding tough sentences of radicalism and activism into that universal font” – as was the propaganda posters pumped out under Russian constructivism.

He agrees with fellow proppaNOW artist Richard Bell’s assertion that “Aboriginal art is a white thing”.

“The popularised desert art and traditional tropes of Aboriginal art began with a false premise,” says Ah Kee. “All the stories and theories and historical groundings going back to the 1970s that underpin Aboriginal art is all a white construction.”

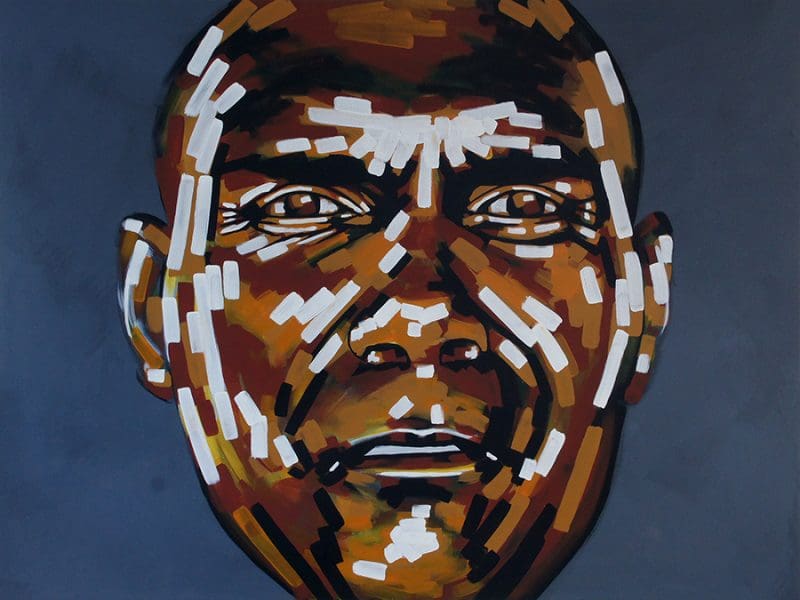

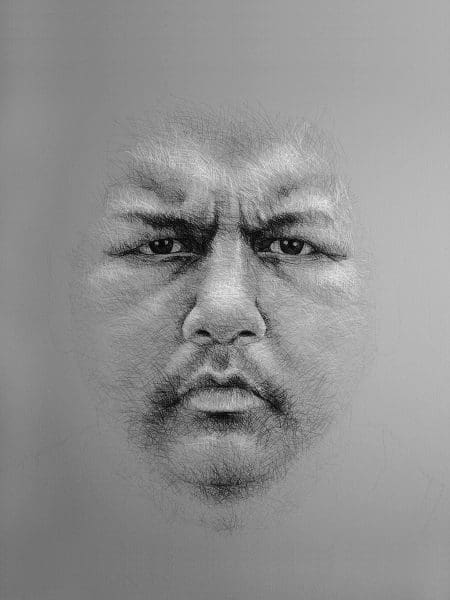

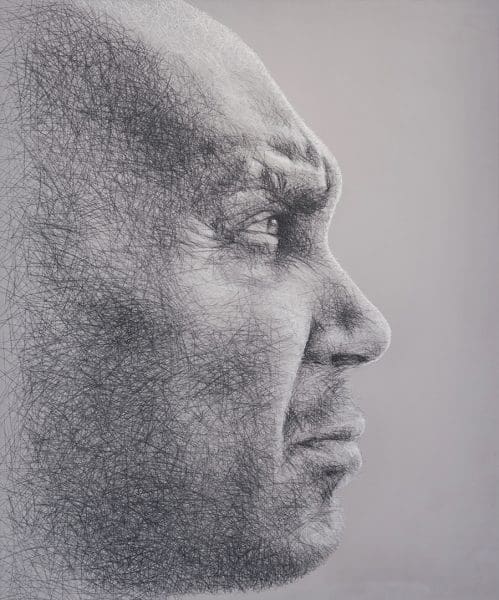

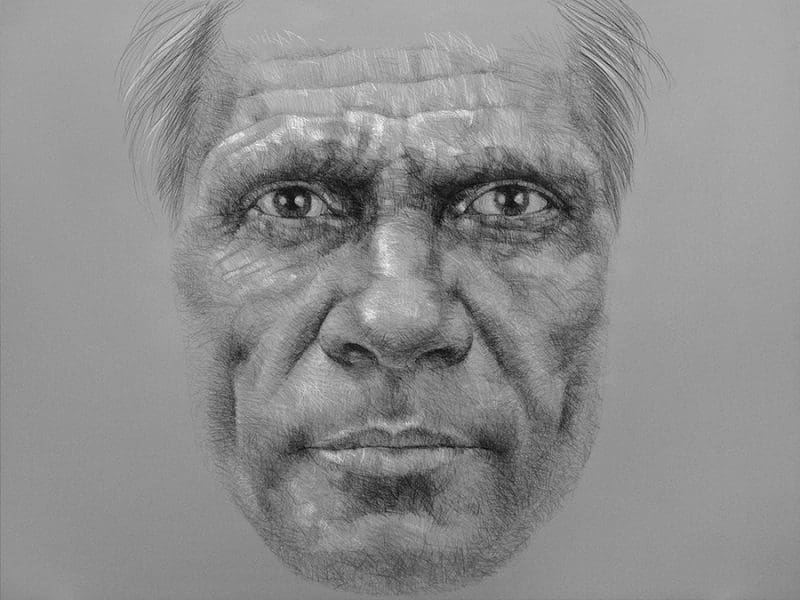

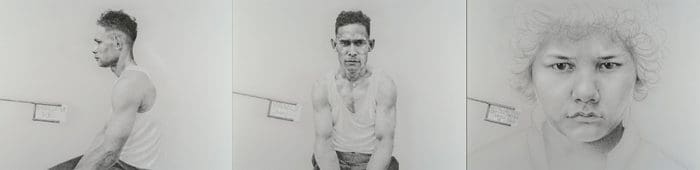

Powerfully, Ah Kee accessed the photographs of anthropologist Norman Tindale taken in 1938 on the Palm Island mission, essentially an Indigenous penal settlement. The subjects include his great-grandfather George Sibley and grandfather Mick Miller. The gaze from each of Ah Kee’s large charcoal portraits is indelible.

There remains one little-explored detail in the Ah Kee biography, however: the artist’s paternal great-grandfather was Chinese. He has an “intellectual” interest in this heritage, though not so much emotionally.

“I know very little about him. We had always known we were Chinese, but because we were born with dark skin and black, curly hair, we were never, ever accepted as being anything other than Aboriginal. I think of myself as completely Aboriginal, because of the way I’ve been treated my whole life.”

Vernon Ah Kee: Not an Animal or a Plant

National Art School Gallery

7 January – 11 March