As a conceptual and pop artist, a photographer and a painter, as well as an idiosyncratic art critic for two broadsheet newspapers, Robert Rooney wielded influence. This achievement is extraordinary given that Rooney, who died on 21 March, aged 79, reportedly spent almost his entire life in his home city of Melbourne.

Rooney left Melbourne only once, in the mid-1980s, to review the Archibald Prize at the Art Gallery of NSW, insists his gallerist, Darren Knight, who first met the artist in 1992. “He absolutely hated it,” says Knight. “He went back via Canberra and had a look at the National Gallery. He said, ‘That was enough.’ He had no desire to leave Melbourne again, and didn’t.”

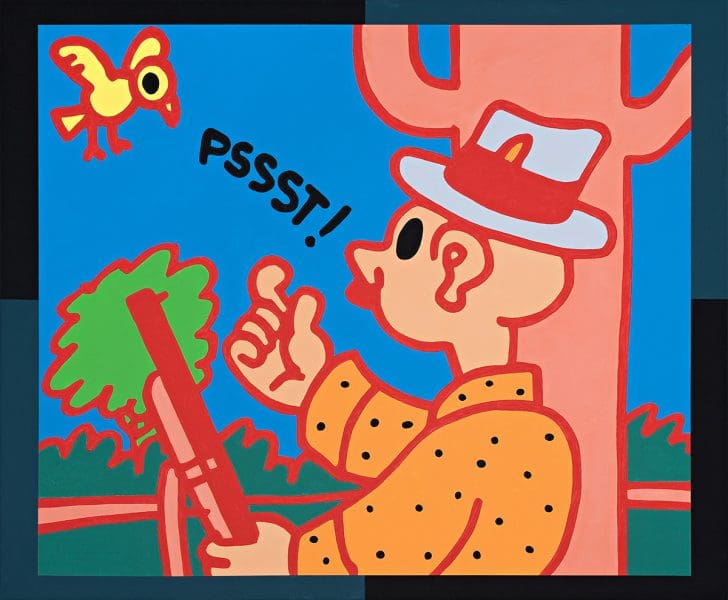

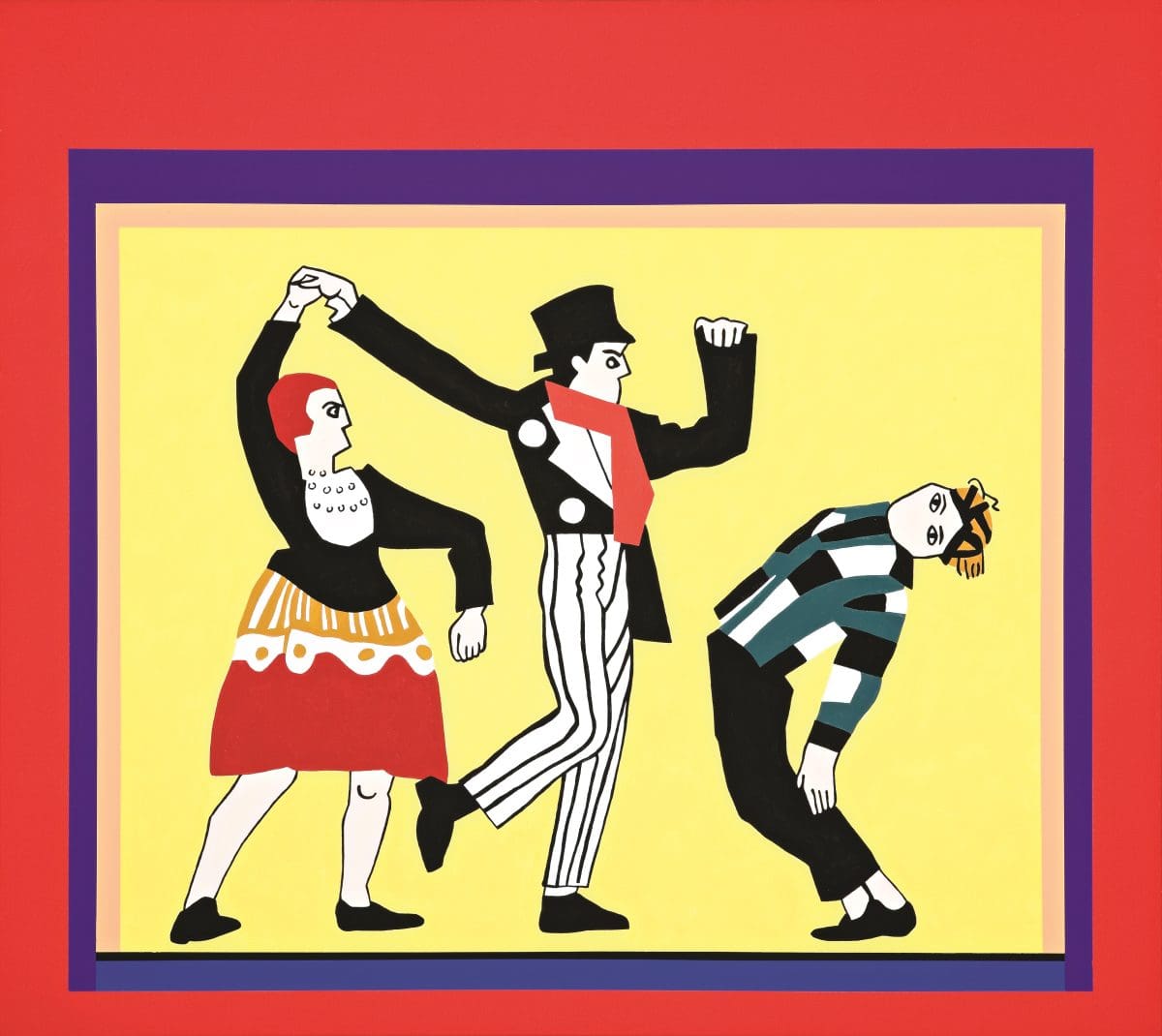

Born in Melbourne in 1937, Rooney lived most of his life in the same Hawthorn home with his mother, Beatrice, who died earlier this year. She had encouraged him as a child to cut up photographs from The Australian Women’s Weekly and paste different heads on bodies. He loved the colour comics in The Sun News-Pictorial, although as a piano-playing child his ambition had been to become a composer. He had an interest in music and ballet.

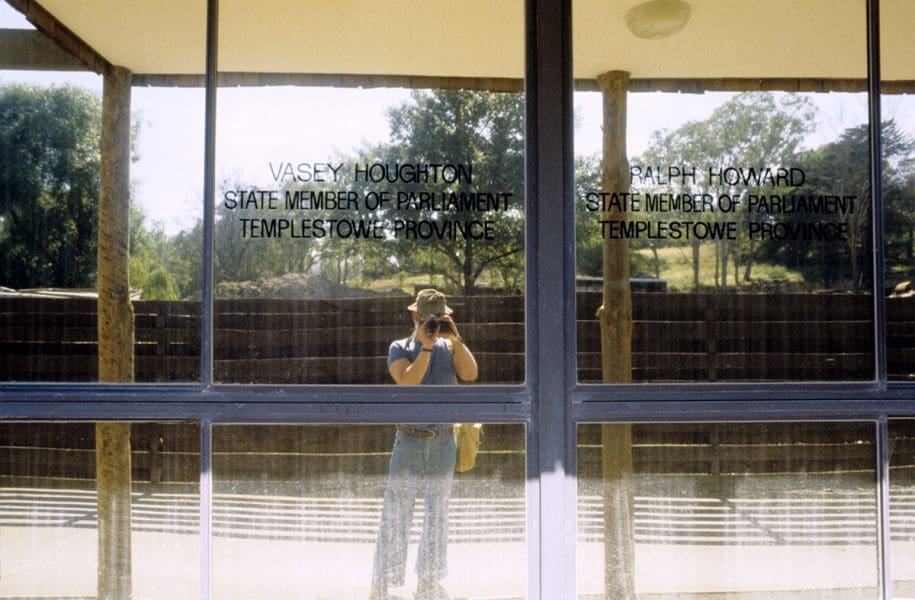

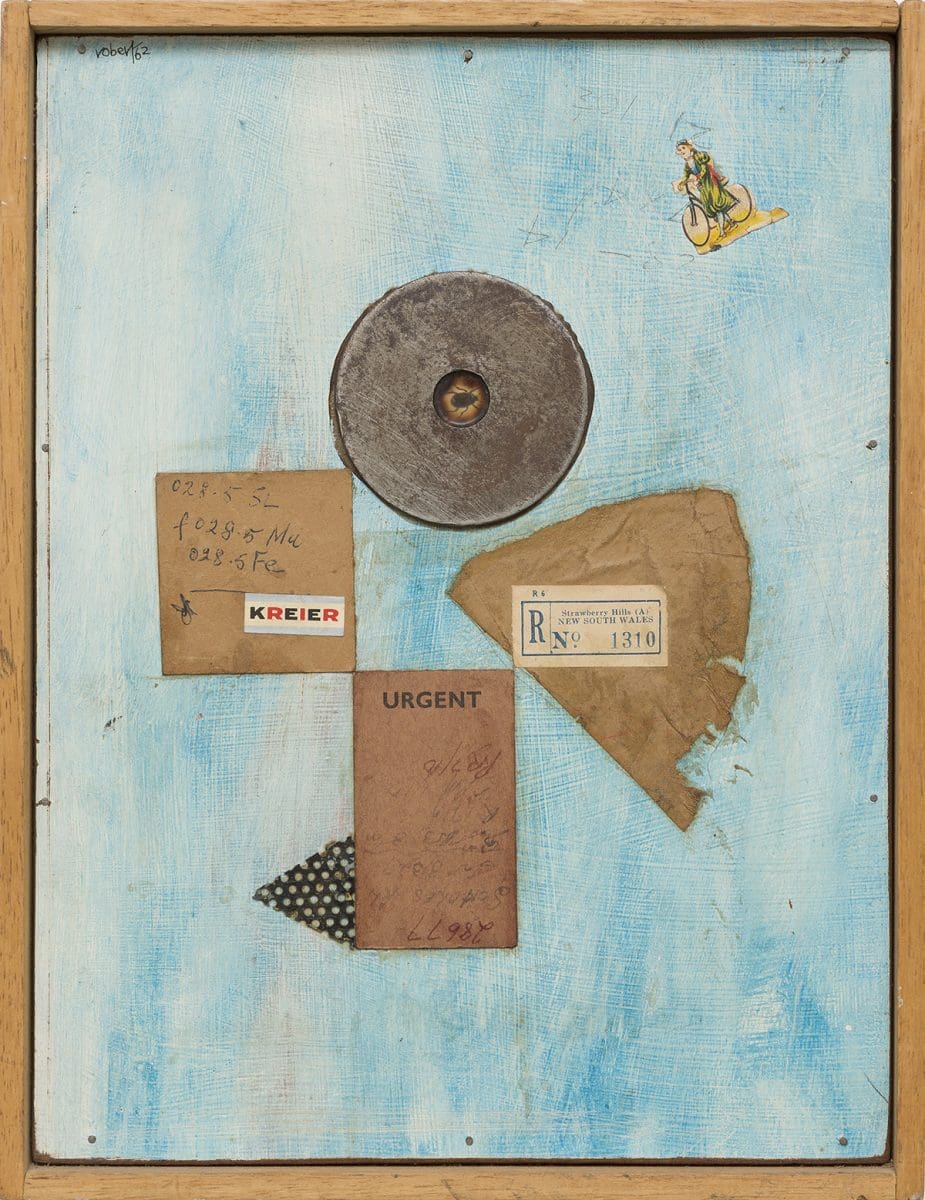

Rooney trained in art at Swinburne Technical College in the 1950s. He would take Box Brownie photographs as references for some of his early drawings, prints and paintings. “Robert took geometric abstraction a step further, as a precursor to the whole conceptual thing,” says Knight. “He found the patterns from the back of cereal packets and knitting patterns: something close to home, domestic and un-grand. So he played around with the formality.”

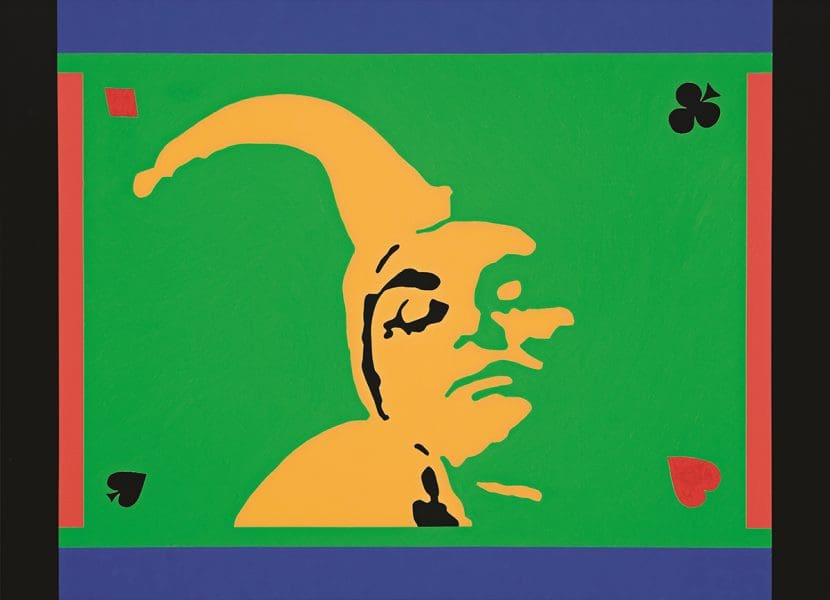

Rooney gained national recognition when he was exhibited in The Field, the seminal 1968 survey of colour field painting and abstract sculpture at the National Gallery of Victoria and then at the Art Gallery of NSW.

In the 1970s he trained at Preston Institute of Technology, and in the 1980s moved away from photography back to painting. His subject matter included ephemera found in books, such as a red Communist Party membership card he’d discovered many years earlier. Knight says that there was never any indication what Rooney’s politics were, “He was probably more humanist than political.”

Shy and uncontroversial in person, Rooney was nonetheless willing to call out the shortcomings of the work of his colleagues in his role as a critic for The Age from 1980 to 1982, and The Australian from 1982 to 1999.

Although Rooney was unwilling to leave his hometown, he kept abreast of art world developments and found inspiration in books, magazines and letters, says Knight. “He worked in bookshops for a long time, where he got a lot of source material. He also had a long, ongoing correspondence with all sorts of artists all over the world.”

Among Rooney’s more significant exhibitions of recent years was Robert Rooney and Conceptual Art, at the NGV in 2010, which surveyed the artist’s conceptual-based works, photographs and works on paper, largely drawn from gifts Rooney had given the institution around that time. In 2013, the Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne, presented Robert Rooney: The Box Brownie Years 1956-58. Knight, who last exhibited Rooney’s works in the 2008 show LE RIRE at his Sydney gallery, says he is not currently planning a Rooney show.

Although Robert Rooney had not been able to make work for his last three or four years, Knight says, “He has to rate highly [as a conceptual artist], purely because of his influence on other artists that followed.”