Kicking Convention

They might have been continents apart, but visual artists Man Ray and Max Dupain were aligned in their experimental vision, as a major exhibition at the Heide attests.

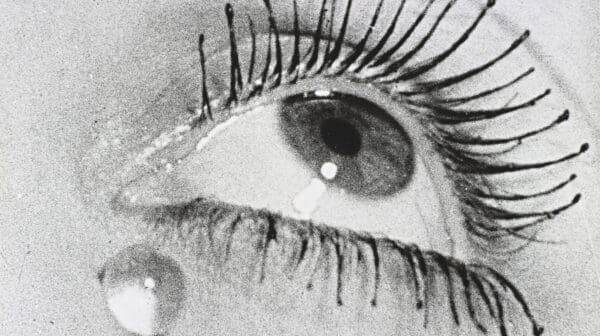

Polixeni Papapetrou, Curtain, 2018, Image courtesy the artist’s estate and Michael Reid Sydney + Berlin.

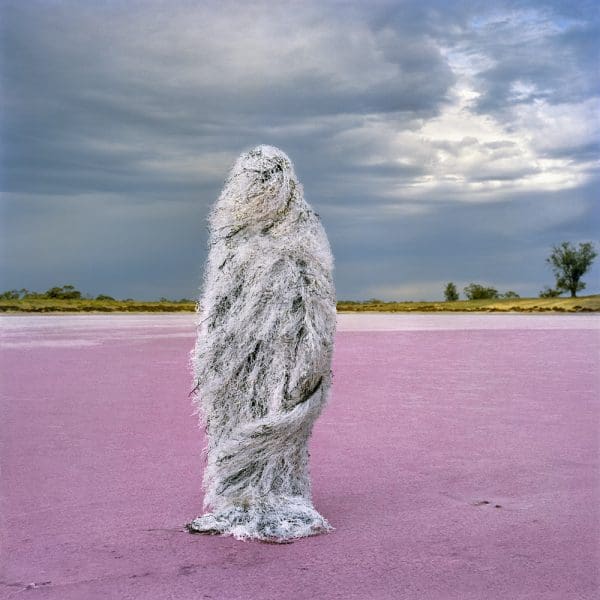

Polixeni Papapetrou, Salt Man, 2013, image courtesy the artist’s estate and Michael Reid Sydney + Berlin.

Polixeni Papapetrou, Magma Man, 2012, image courtesy the artist’s estate and Michael Reid Sydney + Berlin.

Polixeni Papapetrou, Amaryllis, 2016, image courtesy the artist’s estate and Michael Reid Sydney + Berlin.

Polixeni Papapetrou, The Wanderer, 2012, image courtesy the artist’s estate and Michael Reid Sydney + Berlin

Melbourne photographer Polixeni Papapetrou died on Wednesday 11 April, following a long illness.

Widely recognised as one of Australia’s foremost contemporary artists, Papapetrou came to photography later in life and quickly rose to prominence. She initially studied law at the University of Melbourne and worked for 15 years as a commercial lawyer, and it was seeing the images of American photographer Diane Arbus in the mid 1980s that inspired Papapetrou to start making art.

Papapetrou’s earliest images included portraits of artists before she moved on to more elaborately staged works featuring drag queens, Elvis impersonators, wrestlers and body builders. Interested in the blurred constructs of identity, a sense of the theatrical and performative was consistent throughout her work. Over time, her children Olympia and Solomon began to frequent her images, often dressed in costumes and animal masks in front of fantastical backdrops.

Speaking about Papapetrou, Professor Natalie King at the Victorian College of the Arts, described her friend and colleague as an artist who was “immeasurably creative, indefatigable and unstintingly focused on her photographic practice. She skilfully melded her family life with her artistic output, casting her beloved children in her photographs as a way to cherish and conjoin both spheres, while her husband (art critic Robert Nelson) painted her backdrops. Whether producing carefully configured landscape scenarios, masked portraits or emotive mise-en-scenes, she flexed her lens on the human dimension of loss, longing, love and the unknown.”

Within her oeuvre, Papapetrou drew on aspects of art history, literature and fairy tales and this was particularly evident in Wonderland, 2004, a retelling of Lewis Carroll’s famed tale and featuring a young Olympia cast as Alice. This was followed in 2006 by Haunted Country, a series of images based on the Cooper-Duff children who went missing in Victorian bushland in 1864 and Papapetrou’s own childhood experience of being lost in the bush. Continuing to expand her knowledge of cultural depictions of childhood, Papapetrou completed a PhD at Monash University in 2007 which focused on the representation of childhood in photography.

“She has driven contemporary photography forward with a constantly developing style that has found an audience both nationally and internationally. The National Gallery of Australia has 32 of her works in their collection, such was her practice that it demanded in-depth and consistent acquisition.”

Online tributes to Papapetrou have continued to flow with Esther Anatolitis, executive director of NAVA writing on the NAVA blog that, “Polixeni was a sensitive observer of the stories we tell, the roles we play, the masks we wear and the truths we uncover, as we evolve into our individual and social identities,” while playwright and close friend Joanna Murray-Smith described Papapetrou to The Daily Review as, “ferociously female, both feminine and feminist.”

Despite her illness, Papapetrou remained a prolific artist, consistently exhibiting solo exhibitions and regularly included in significant group shows, both nationally and internationally. Over the past decade, she was the recipient of numerous awards, most recently for Delphi, 2016, a portrait of a young woman resplendent with flowers which won the acquisitive William and Winifred Bowness Photography Prize in 2017.

Papapetrou delivered her final exhibition to Michael Reid Gallery two weeks ago. Speaking about the impact of the show, MY HEART – still full of her, Meagher concluded, “Since 2002, Polixeni’s practice focused particularly on childhood, adolescence and identity. Her work loosely mirrored the ageing of her own children, and these themes developed in tandem over time. MY HEART – still full of her is in many ways, a completion of that grand narrative arc. Polixeni introduces herself as a subject for the first time; interrogating her role as artist and mother, collapsing her own identity with that of her daughter.”

Polixeni Papapetrou’s funeral was held on Tuesday 17 April at St Eustathios in South Melbourne and was followed by a wake at the Centre for Contemporary Photography.