As a school-leaver in the late 1940s, James Mollison went to the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) seeking an advertised internship to train as a curator. He had memorised the gallery’s collection. And while the internship never eventuated, he spent an enjoyable afternoon in the print room looking over Rembrandt etchings.

He learned his first real lesson about art that day. He would write years later, in an 1988 essay, that art “is more enjoyable if you look at it hard and long, than if you look at it idly and in passing.”

Australia’s art world is mourning Mollison, founding director of the National Gallery of Australia (NGA), who died aged 88 on 19 January 2020.

In recollecting his teenaged self, Mollison wrote that after leaving school he “knew nothing about art.” Yet there is undue modesty in this anecdote, says Mollison’s long-time colleague and friend, Grazia Gunn, who is writing a book on the early years of the NGA, which will be titled The Mollison Years.

“I have stories from him when he was even younger, when he was at school, and about how much he loved colour,” says Gunn, who between 1981 and 1989 served as curator of international current art while Mollison was director at the NGA. “He was a huge fan of colour, he discovered that when he was very, very young.”

Mollison was the driving force behind the NGA’s strong art acquisition policy, first as acting director from 1971 to 1977. The gallery opened in Canberra in 1982. Mollison was NGA director from 1977 to 1989, before becoming director of the NGV from 1989 to 1995.

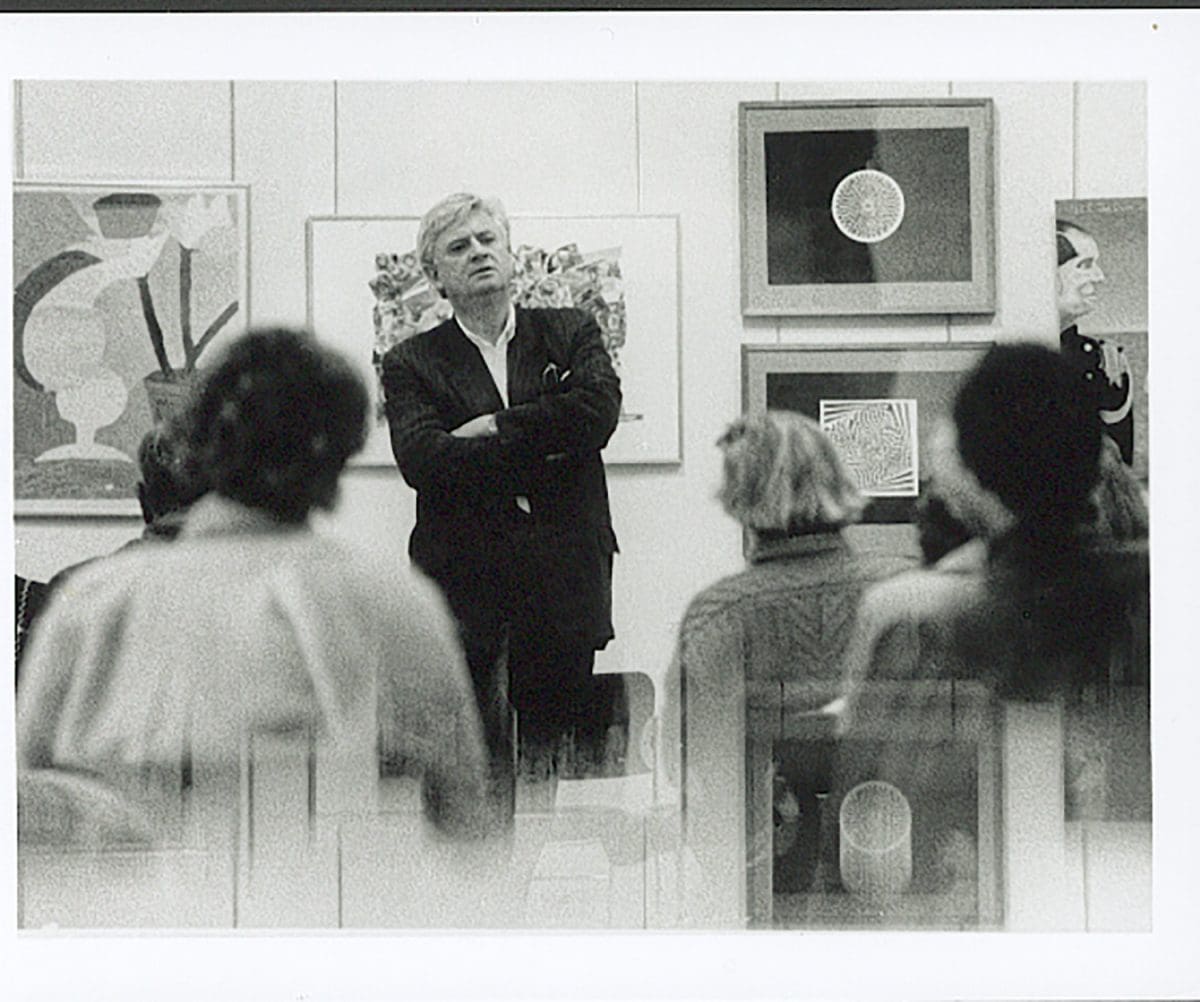

“James had an incredible ability when he did an exhibition – he’d put works next to each other that had an affinity that nobody else had realised before him,” says Gunn. “He really was well ahead of his time, in putting Australian art with global art, and wanting to be a part of the world.”

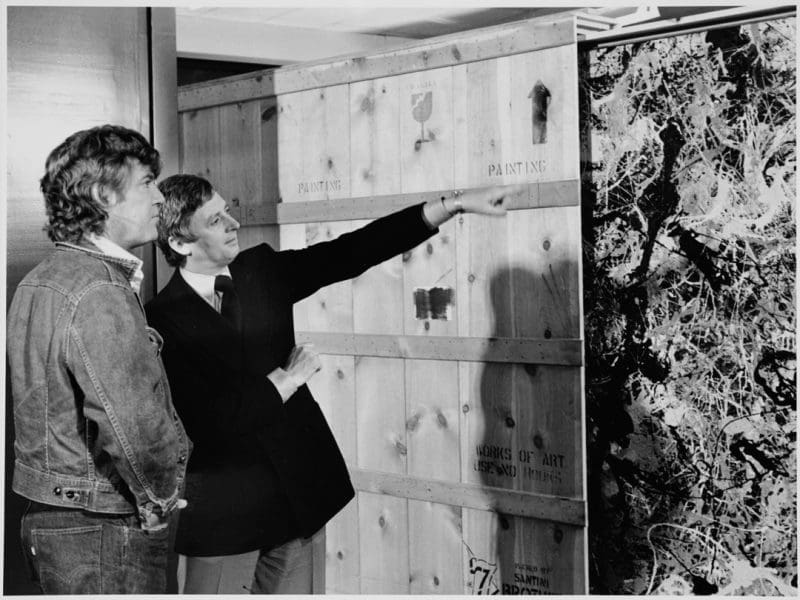

Mollison was also “incredibly quick to realise that the second wave of modernism was happening in America,” says Gunn, “even before the Americans themselves realised the importance of what was happening there. They were still looking at abstract art. Jackson Pollock was the major American artist of the second wave of modernism.”

Famously, the NGA’s 1974 purchase of Pollock’s Blue Poles for $1.3 million met with some public and media derision.

Did Mollison feel vindicated by the change in mood over time towards the purchase? The current director of the NGA, Nick Mitzevich, responds, “I know he felt haunted by [the reaction], that it was always brought up. I can understand that because what James did here went well beyond one painting.”

As Mitzevich explains, “There were many other works that were equally challenging and equally as important to add to the collection; Blue Poles is emblematic of a whole series of things that James did. James undertook the job with a sense of great responsibility. I don’t think he felt ‘vindicated’ [about buying Blue Poles] because he knew it was the right decision from the very beginning. He had a great sense of authority and confidence about such matters.”

Some three-quarters of the gallery’s American masters collection was purchased by Mollison before the gallery opened. “He had a job that was totally unique in this country: assemble a collection from scratch, and represent a collection that would take the pulse of the history of Australian art and also bring the best of the world to Australia, before the building opened in 1982,” says Mitzevich.

“James’s job description was extraordinary but he matched it with his ability to rise to the challenge. He was one of Australia’s greatest museum directors.”

Mollison also commissioned the Aboriginal Memorial of 1987 – 1988 that is positioned at the NGA entrance. Was he commissioning with foresight about the nation’s changing mood towards its past of Indigenous dispossession?

“I think he was commissioning with foresight, that’s a very beautiful way of summing it up,” says Mitzevich. “He was writing art history. We hadn’t seen that before. He was really ahead of the pack. Sometimes we just have to take a breath and consider what he was doing, because he was further ahead than anyone else.”

Tony Ellwood, director of NGV, says Mollison was an “incredibly visionary leader. He took creative risks ahead of his time in the display and interpretation of art.” Ellwood says Mollison “transformed” the NGV during his directorship there “introducing many new ideas, people and key acquisitions including major contemporary works. He was a great advocate for living Australian artists and a mentor to many art museum professionals. He has left an enormous legacy across the country and will be greatly missed”.