Bar the historic trade between Makassar fishermen and Yolŋu people, the relationship between Indigenous Australia and Asia is rarely mentioned. The Neighbour at the Gate, an exhibition at the National Art School (NAS) Gallery in Sydney, shifts our gaze to the ongoing and potential connections between First Nations and Asian-Australian communities, bringing together newly commissioned works from around the country.

Curated by Clothilde Bullen OAM (Wardandi Noongar and Badimaya Yamatji), with Zali Morgan (Whadjuk, Ballardong and Wilman Noongar) and Micheal Do, the exhibition draws on intertwining narratives of ritual, culture, migration and nostalgia.

While the legacies of colonialism linger, The Neighbour at the Gate centres the beauty of cross-cultural exchange, unearthing common ground and parallels between two cultures. In Pardu (2025), James Tylor (Kaurna, Maori) pairs daguerreotypes of native birds with audio of birdsong layered over Kaurna instruments. In the Kaurna language, birds are named after their distinctive calls, a practice common in Asia too.

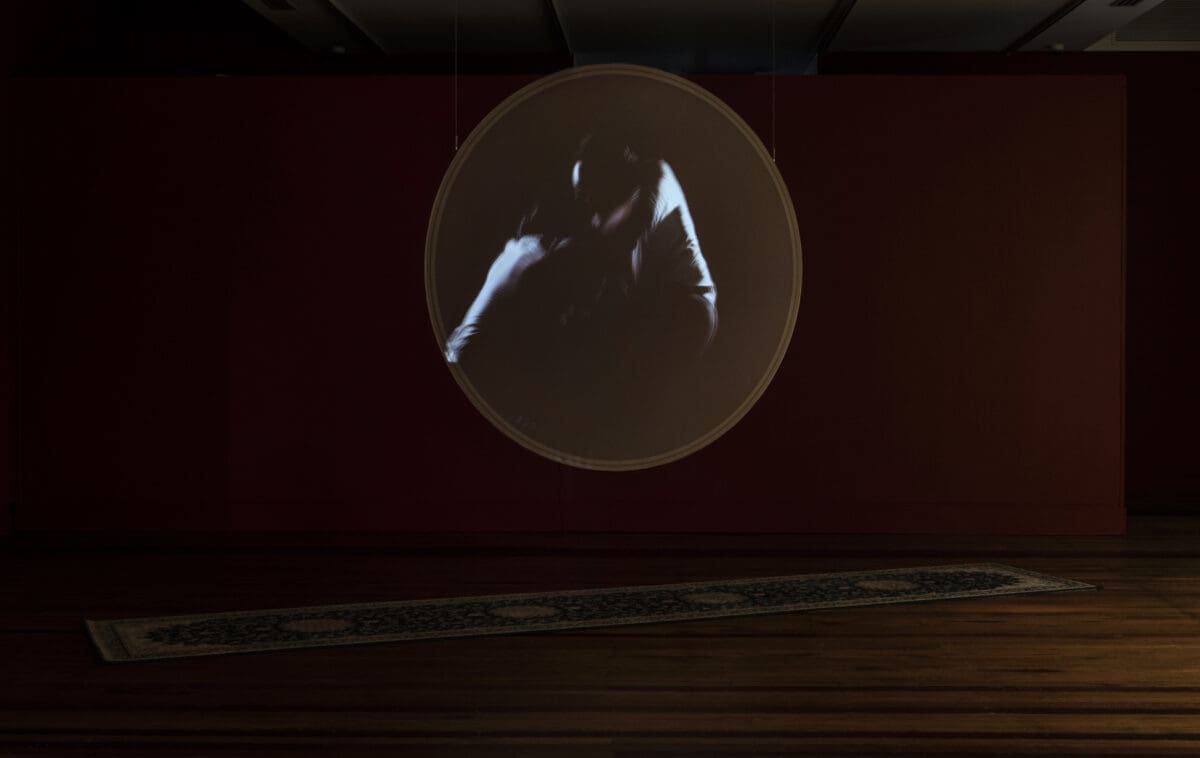

Jenna Mayilema Lee’s Portal to the Bangarr (billabong) (2025), is an immersive video and installation work representing her family story. Lee is proudly Gulumerridjin (Larrakia), Wardaman and Karrajarri, Japanese, Chinese and Filipino. Her Aboriginal-Asian family doesn’t fit neatly into the typical migrant narrative, but Lee sees the duality of her heritage encapsulated by the lotus—a plant native to both Asia and northern Australia.

In Lee’s billabong are paper lotus flowers, crafted from copies of her Asian relatives’ archival immigration documents. Onscreen, the artist slices and boils lotus root as her father Chris ‘Bandirra’ Lee whispers “gwoyarr-ma”, the Larrakia word for lotus. “My dad always described billabongs as our grocery store,” she tells me. “It provided sustenance. In them are lotuses, fresh water, wetland birds—staple food sources.”

In presenting lotuses as food, Lee creates a sharedpoint of reference. She wants to help Asian diaspora recognise their connection to First Nations people through her own family story. “So far, everyone Asian who has walked in has understood and shared with me what the lotus means to them. It’s a connector,” Lee says.

Why is it that ties between Indigenous and Asian-Australians have largely remained unseen? Lee raises the struggles of her dad’s generation. “They had to fight so hard to assert their Aboriginal presence that their other identities needed to take a back seat,” she says. “But now we have this moment where we can explore what being Aboriginal and is, in a way that doesn’t negate our Aboriginality.”

Bullen, who led the curatorium, theorises that these stories go unheard because Aboriginal and migrant communities historically married in the top end of Australia, or in urban areas without “access to dominant culture.” It was Bullen’s experience growing up Perth’s ‘KGB’ (the suburbs of Koondoola, Girrawheen and Balga) that gave her the idea for the exhibition. “For us, Asian-Australian mob are not only neighbours, but often kin,” she explains. “I’ve always had the idea of talking about this whole ecosystem that white Australia has no idea of.” In a time when Australia views its Asia-Pacific neighbours through a military lens, Bullen wants to unite, not divide. “How do we bring back a sense of community?”

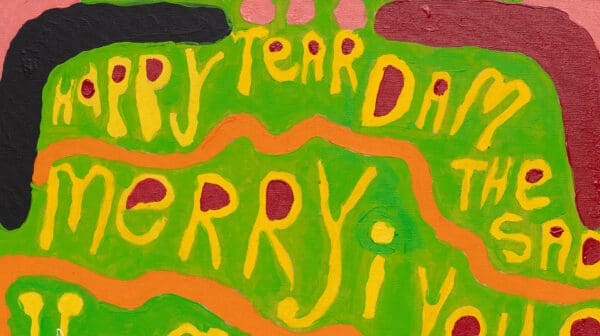

The strength and resilience of community spaces is celebrated in Dennis Golding’s Bingo (2025). The Kamilaroi artist created over 100 etchings on paper, each decorated with memories of the bingo nights his nan and aunty hosted throughout the 1990s and early 2000s. Held in an abandoned terrace house in Redfern’s block, the events were invisible to the outside world, but a sanctuary to the Aboriginal community gathered within. “We needed a sense of peace away from the noise, the police surveillance,” Golding says. “My aunties cleaned up the house, got the curries and cupcakes going. You’d feel the warmth of everyone around. It was filled with love and joy.”

While The Neighbour at the Gate is a coming together, it does not easily ignore the pain of displacement. Iranian-Australian artist Elham Eshraghian-Haakansson’s God of War (2025) deals with the rage and inherited trauma of the refugee experience. James Nguyen’s Homeopathies_where new trees grow (2025) is a textile work dyed using weeds and mud from the Parramatta and Duck River contaminated by Australian-made Agent Orange—the same war chemical sprayed on Nguyen’s family farm in Vietnam. Titled Imaginary Homelands (2025), Broome-based Malaysian-Chinese artist Jacky Cheng’s wax paper paifang gate is a portal to her ancestor’s country. It is also a transitional space, welcoming, or excluding, those who stand before it.

In early discussions between the artists and curatorial team, the group considered the knowledge purposely kept from immigrants. “The idea of information quarantined at the gate,” Bullen says. “The government not teaching Aboriginal culture, pretending we don’t exist.” In this way, The Neighbour at the Gate is an invitation, or “call in” as Bullen puts it. “We need to have this gathering space to reflect on where we come from, who we are and what we share between different cultures,” Golding reflects. “This is a beautiful way to have these conversations.”

The Neighbour at the Gate

NAS Gallery

(Sydney/Gadigal Country NSW)

Until 18 October

This article was originally published in the September/October print edition of Art Guide Australia.