A search for beauty is behind Skin tight, the first solo exhibition in Australia for the American artist Tschabalala Self, whose works seek to alter the power dynamic between viewer and subject.

While making new works for Skin tight, her exhibition at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA), American artist Tschabalala Self found herself pondering an unfashionable question: is it worth striving for beauty in art?

“When you’re in art school, there is a culture of undermining the intelligence of beauty—you think things that are beautiful are decorative or trite. And it’s not just in art school,” says Self. “Overall, our culture has become more cynical.”

Since the horrors of the 20th century, and in today’s world of continuous crisis, many artists have used their work to investigate humanity’s darkest sides. In a time of war and climate catastrophe, it can be hard to argue for the importance of making beautiful art, or even for the idea that people deserve it. But throughout much of Western history, creating beauty was seen not as a shallow undertaking for an artist, but a valuable one: from ancient Greece through to the Romantic era, beauty was used in art to communicate ideas of harmony, of humans’ capacity for self-improvement and of hopes for a brighter future.

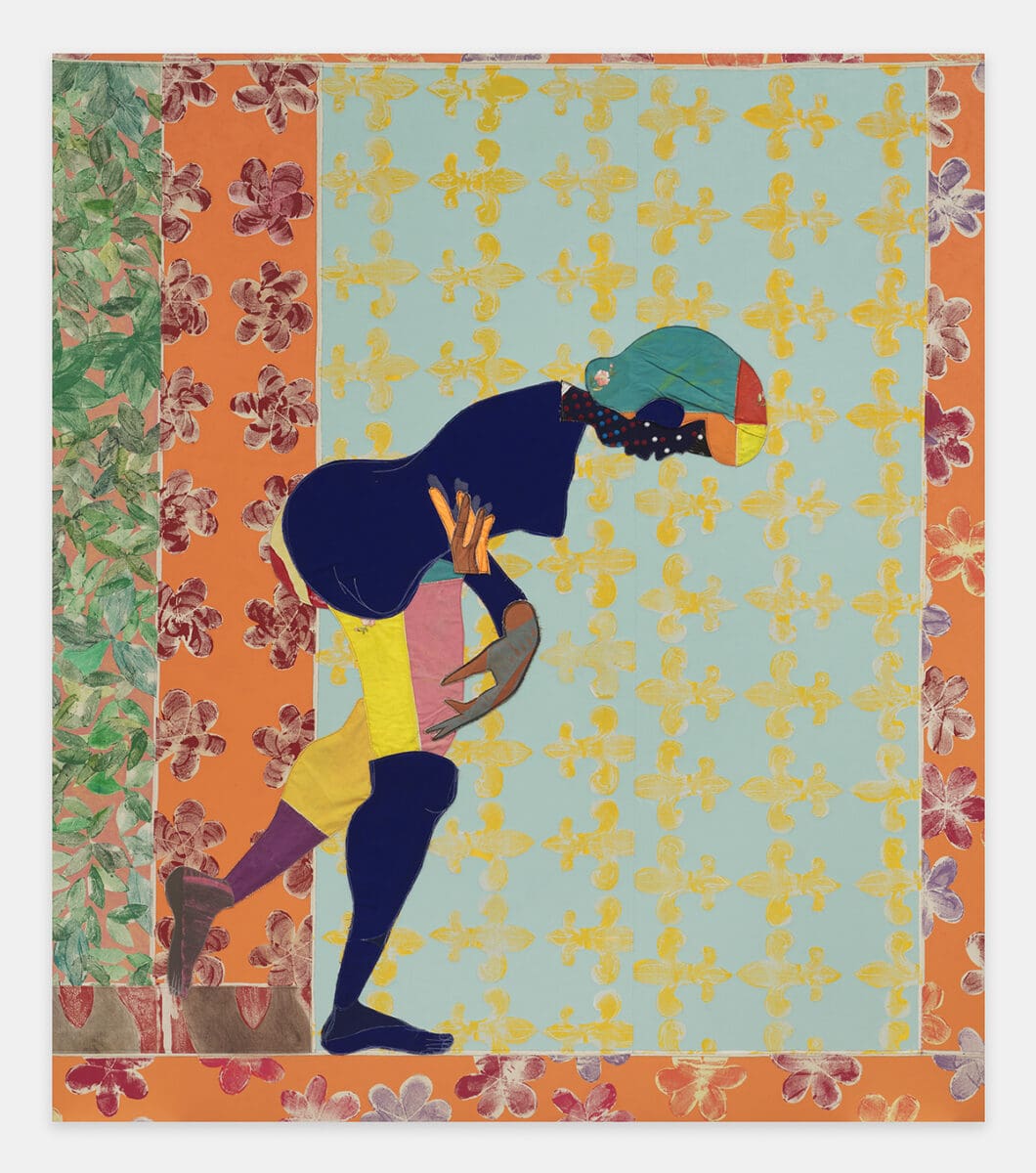

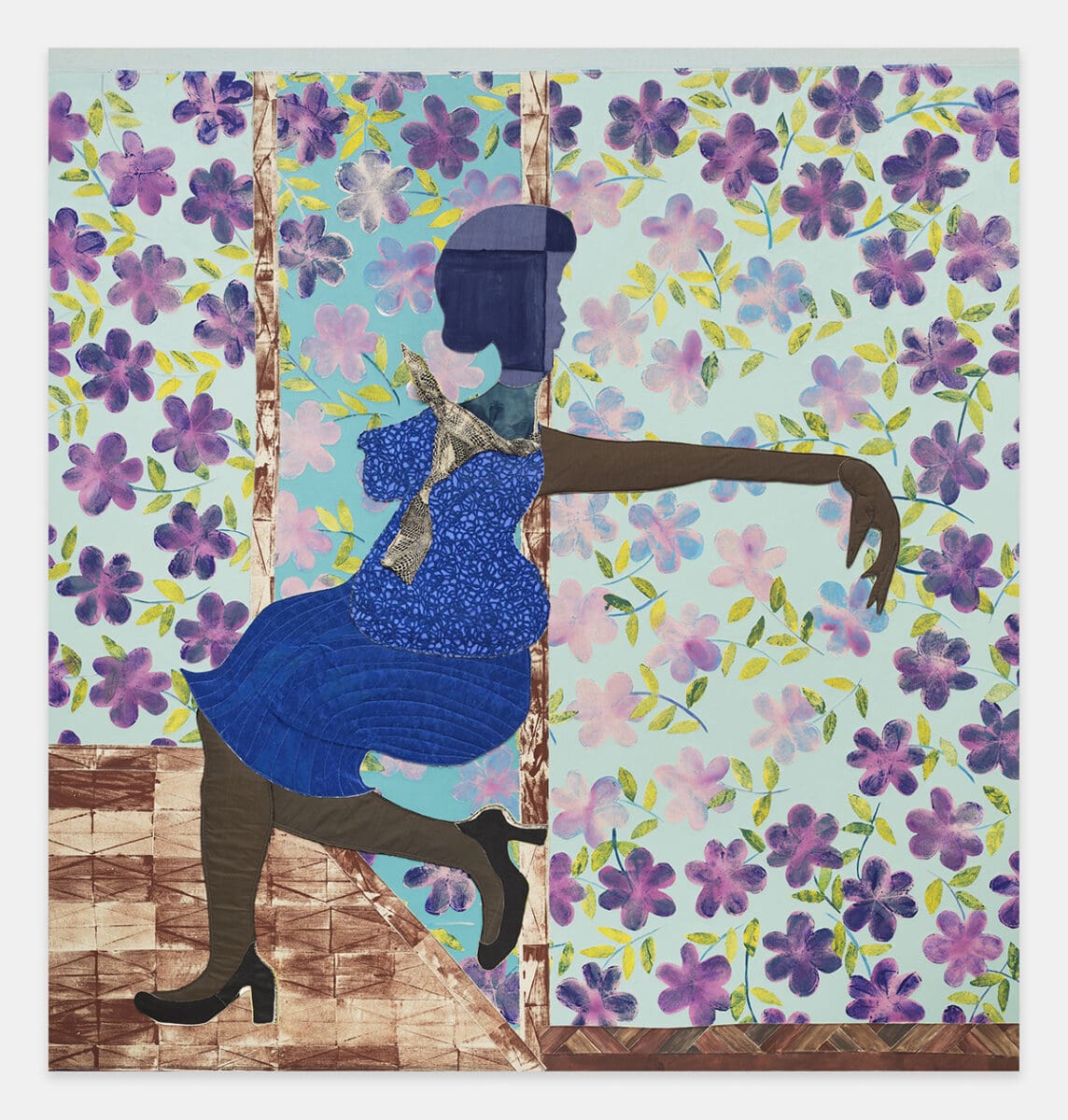

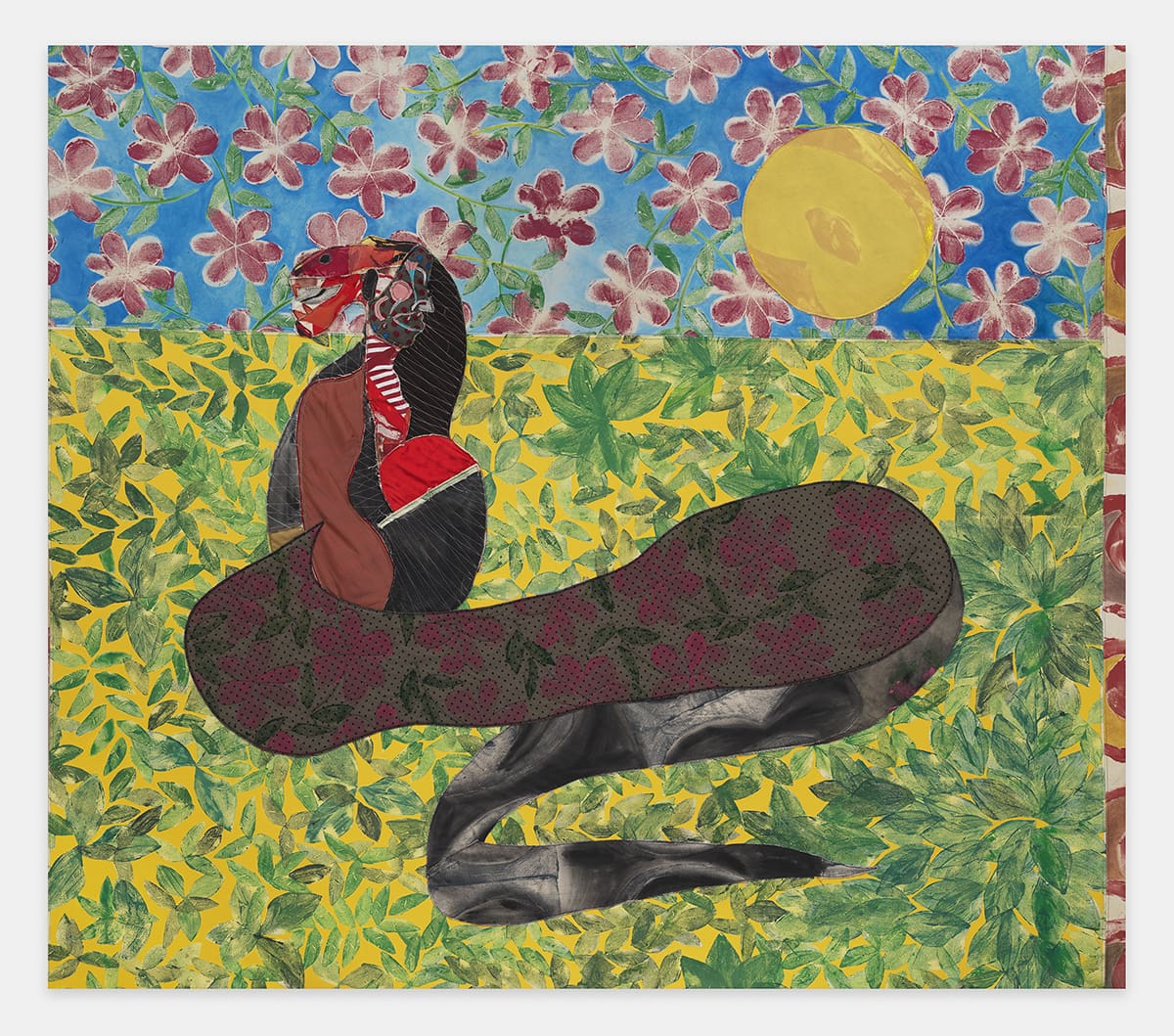

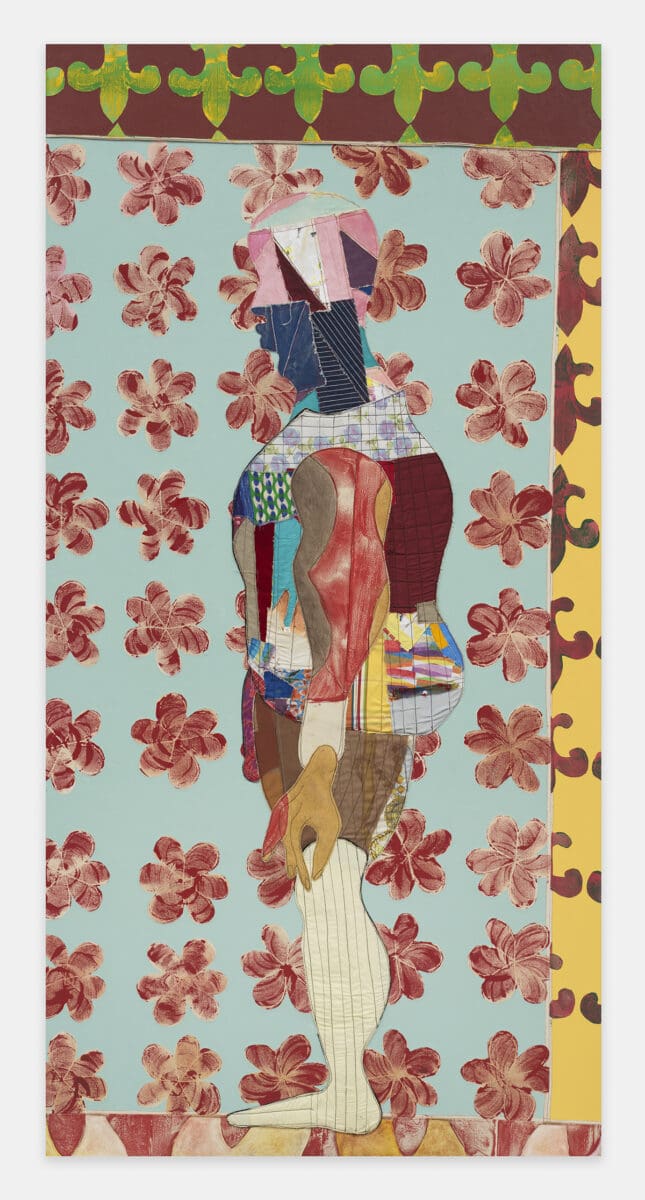

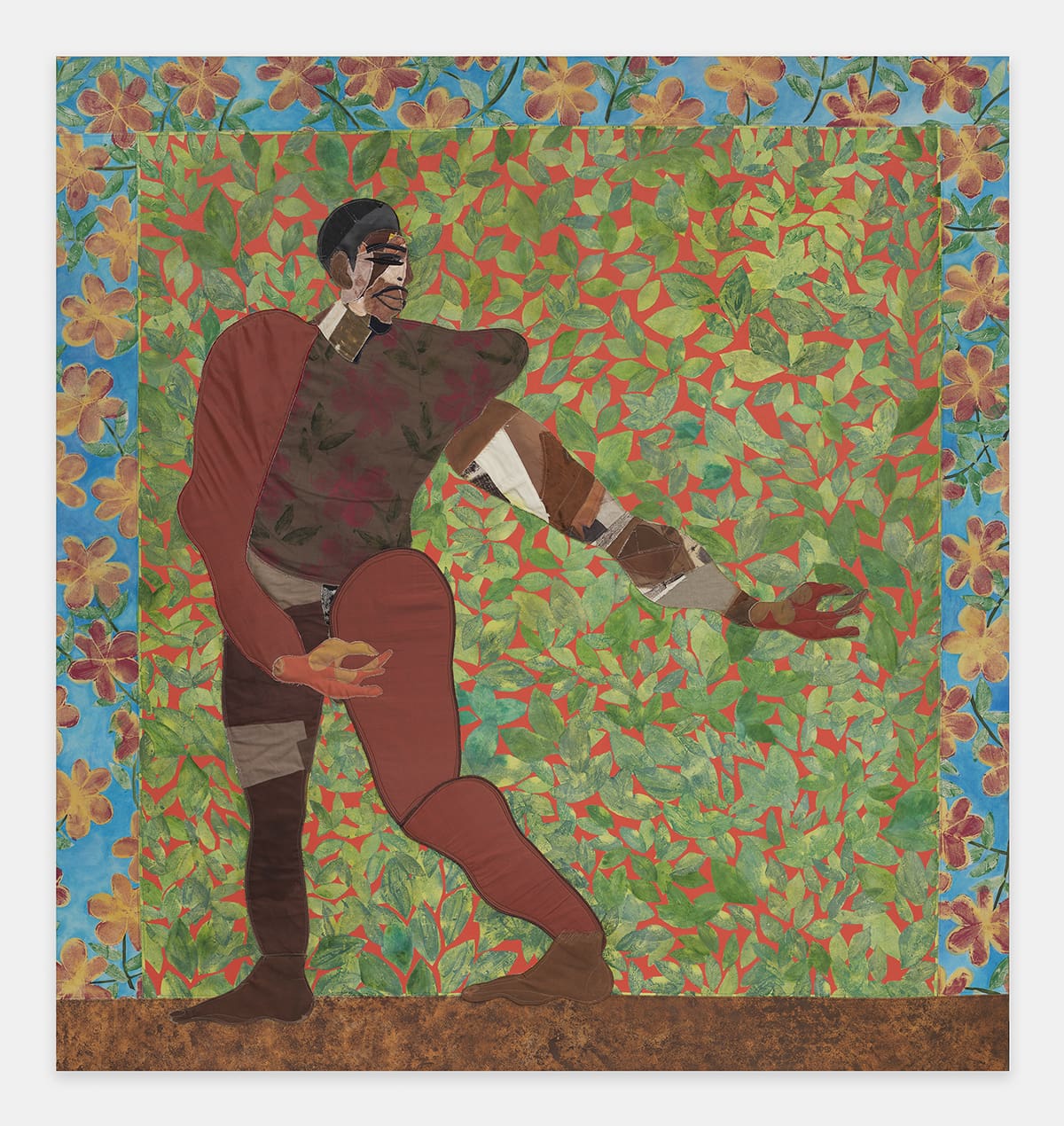

A search for beauty drove the production of Skin tight, which is Self’s first solo exhibition in Australia and the latest in a long list of major shows she has had around the world. Over the past decade, Self’s exuberant depictions of Black people have been exhibited to critical acclaim at institutions such as the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art and the Yuz Museum in Shanghai. She works in multiple media, including sculpture, video, drawing and printmaking, and has received especially high praise for her collages on canvas that are loosely described as paintings.

These feature fabrics of all kinds, some of them painted or dyed by Self, sewn together to make empowered Black characters.

Self’s use of materials is key to understanding her works. Her characters are usually composites of people she remembers from her childhood in Harlem or elsewhere, rather than specific individuals, so collaging them—making them physically multifaceted—underscores the idea that everyone is multidimensional and therefore impossible to reduce to stereotypes.

Working with fabrics, including discarded clothes, also roots Self’s art in everyday life, rather than in the rarefied white cubes in which it is often viewed. Self is so concerned with the context her work is seen in that she often alters the galleries in which it is exhibited. Most famously, when her Bodega Run series was touring, she turned each gallery into a bodega, a family-run corner store, by making wallpaper that mimicked supermarket shelves and sculptures out of stacked plastic crates.

“It’s an attempt to have the viewer become part of the universe of the figures, as opposed to having the viewer take the position of an observer of the figures,” says Self. That changes the power dynamic between the viewer and the subject, challenging the ways in which Black people, specifically Black women, have been objectified in art throughout history.

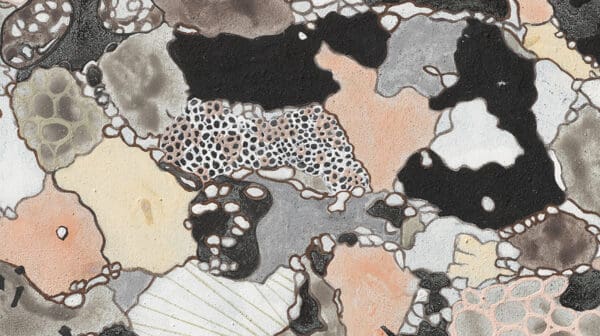

At ACCA, Self has built a new kind of environment for her art. The exhibition features new and recent large-scale paintings, works on wood panels and a video installation. These are installed across a gallery transformed into a domestic setting; a room framed as the Garden of Eden, which features a new painting of Adam and Eve; and characters placed in what Self describes as “liminal spaces” made up of grids like those in her collages. “Those figures are meant to be understood as existing in a certain state of mind, an emotional space,” she says.

That reveals her ambitions for the show. “It is not as pointed a project as something like Bodega Run,” says Self. “This show is more symbolic and poetic. The title, Skin tight, references it: it’s a means to talk about the limitations of the corporal experience, feeling like your body is something that can be tight around your true self, your inner self.”

Several factors inspired this new direction, including ACCA’s sprawling galleries. “The space itself is so expansive that it inspired me to be expansive in terms of my thinking,” she says.

Self’s approach was also shaped by how people from different cultures have engaged with her work over the past few years. Her exhibitions have sparked conversations about race, gender and identity, as well as some universal questions. “What does it mean to be embodied? Every single human being has that experience,” says Self. “When I see similarities between how audiences from all over the world engage with my work, it is very moving for me. It shows the commonality between human experience. Ultimately, it is the foundational mission of my work to investigate and explore that.”

Finally, Self was influenced by her immediate surroundings. After growing up in Manhattan and studying at Yale in Connecticut, she now lives and works in the Hudson Valley outside New York City. Being immersed in nature has made Self reflect on humanity’s place in the broader universe, which she says is easy to lose sight of in the concrete canyons of cities, where you can’t even see the stars at night. It is also what led her to thinking about beauty. “The beauty of a landscape, the beauty of nature, is so sublime,” she says. “I’ve come to reappreciate the supreme intelligence that exists within beautiful things—and it has become a newfound aspiration for me in my own artistic practice.”

Tschabalala Self: Skin tight

Australian Centre for Contemporary Art

(Melbourne/Naarm VIC)

12 September—23 November

This article was originally published in the September/October 2025 print edition of Art Guide Australia.