Material curiosities: Primavera 2025

In its 34th year, Primavera—the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia’s annual survey of Australian artists 35 and under—might be about to age out of itself, but with age it seems, comes wisdom and perspective.

Like many quotable quotes, we owe the saying “the truth will out” to William Shakespeare. It comes from his 1596 play The Merchant of Venice. And although this work is usually classified as a comedy, the dark connotations of the playwright’s phrase are made clear by the fact that to make his point he mentions the act of murder. As Shakespeare so perceptively noted, foul deeds almost always come bubbling to the surface.

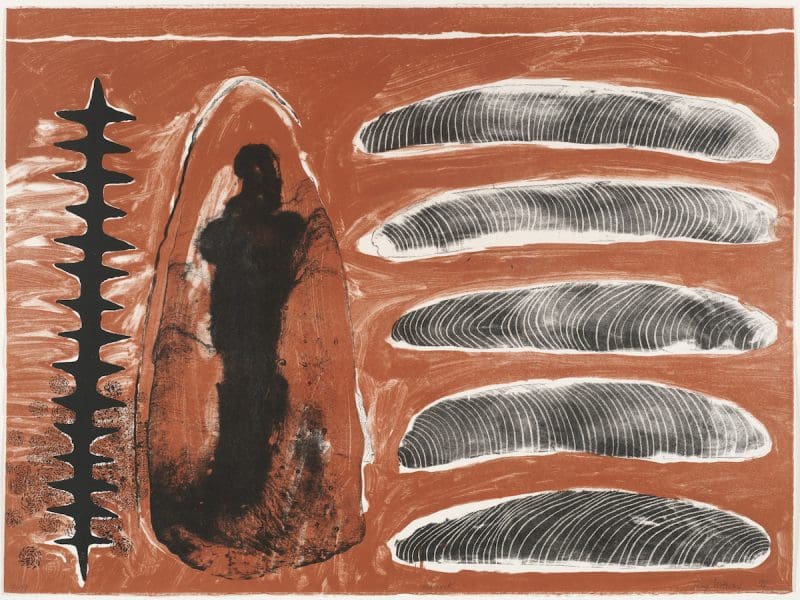

We can see this process taking place as we re-examine the historical treatment of our First Nations people. Slowly, painfully, we are being asked to publicly acknowledge that words like invasion, massacre and slavery do apply to the history of this country. The truth is coming out, for history is more than just the official version of events recorded (a euphemism in this case for white-washed, by white men) to suit the needs of those in charge. History is also memory, stories and culture, and these can never be fully suppressed. And it is Aboriginal artist Judy Watson’s ability to use the power of memory to illuminate the effects of history – particularly those deliberately hidden or ignored – and to reveal the resilience of familial stories and Indigenous culture that is being explored in the survey show The Edge of Memory.

“All of the works touch on memory in some form,” explains Cara Pinchbeck, senior curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, “what is remembered and how this is remembered – whether this be personal memories of past events in Judy’s family, the traces of the past that are present within Country, environmental issues (particularly water), historical violence that lingers within Australia today, or more recent horrific events that allude to an uneven balance of power. This tenuous balance is central to the show, hence the use of ‘the edge of memory’ in the title.”

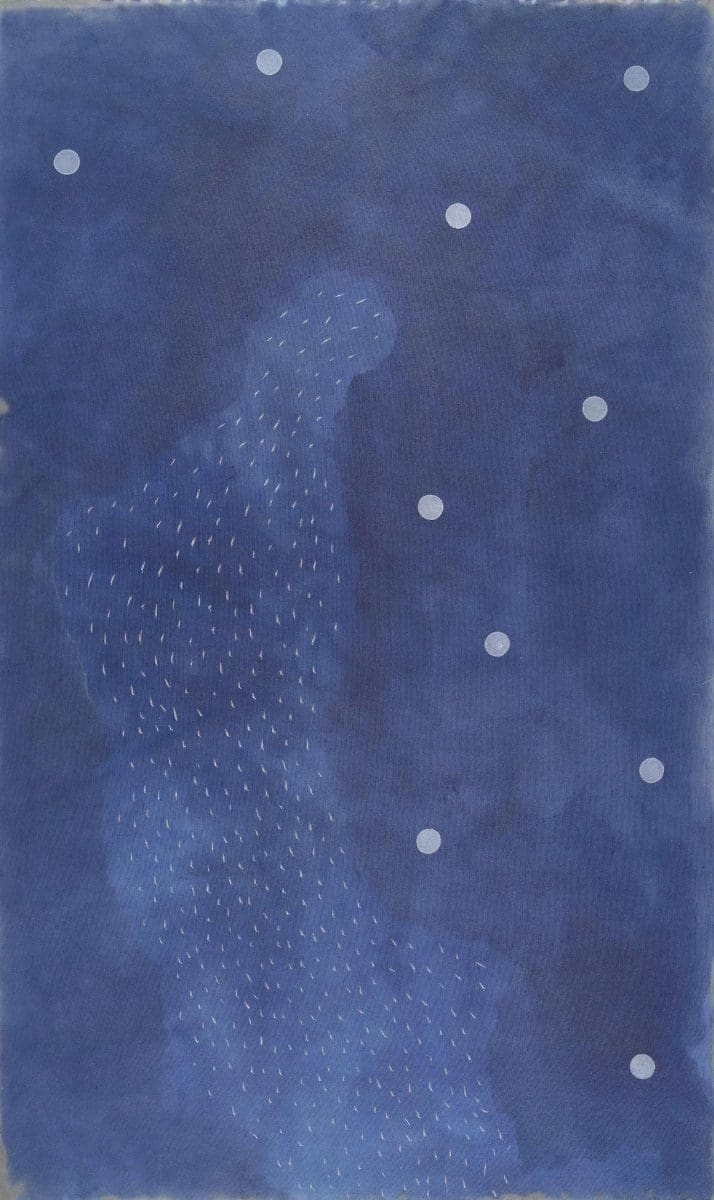

Pinchbeck has borrowed this phrase from Watson’s 2007 work, Passing from the edge of memory to the night sky, which can be seen in the show. A layered painting covered in watery washes of deep indigo, this work is about both presence and absence, tenacity and surrender. It perfectly highlights one of the strengths of Watson’s practice; the willingness to use the seductive power of beauty to start a conversation about difficult topics. “I sometimes want the work to be quite beautiful and compelling so that you are drawn into it, and it is sort of like you swallow it before you realise what is going on, or what the content is,” says Watson. As she puts it, deducing meaning in art can be “like osmosis, it leaks into you.”

As Pinchbeck explains, this is the core strength of Watson’s art, the advantage it has over other methods for communicating difficult subject matter. “Through powerful visual forms, Judy’s works offer a space for contemplation that is much more sensual and emotive than history writing, hard-hitting facts or documentary imagery to which we have become desensitised. Her works commemorate loss while exploring enduring hurt and pain,” she says.

Although Watson, who represented Australia in the 1997 Venice Biennale, is known for works that reference her Waanyi matrilineal linage, she has also made work that acknowledges her Scottish/English/Australian heritage on her father’s side of the family. “I’m not evading that,” she says. “Usually when I give talks I say ‘It’s like in The Blues Brothers movie when they were told there were two types of music: Country and Western.’ And I say well, ‘I am Country and Western.’ I come from Northwest Queensland, that is my Country, but I have been through the Western education system too, and I do have a Western European aspect to my family, as well as the Aboriginal, as do many of us.”

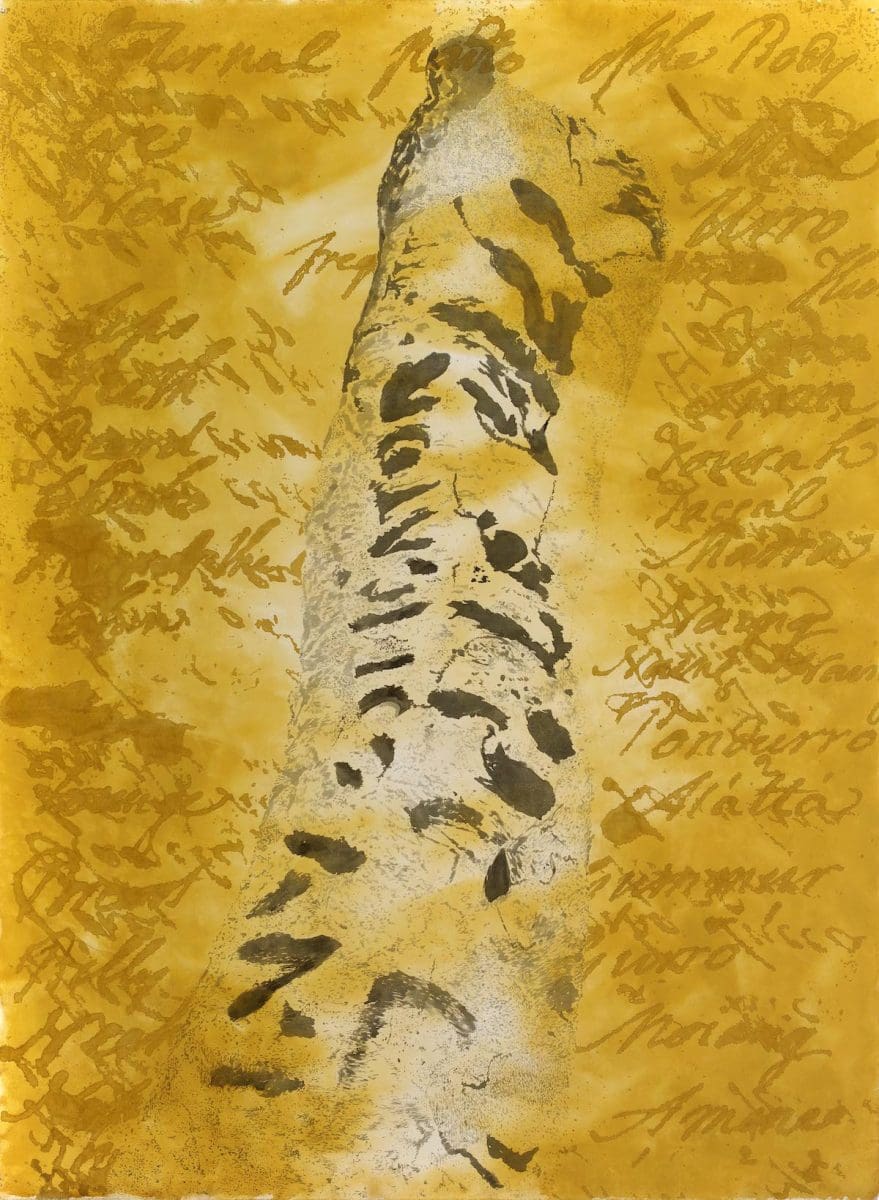

And Watson is also keen to point out that not all of her work is about tackling the toxic legacy of colonisation head on. “Sometimes the work is just the process itself,” she explains. “It’s a conversation I have with the work, whether it’s with the paint, or the rubbings on the surface, or a particular substructure; it’s all this conversation between you and the work and it will lead you to a completely different place.”

Having said that, Watson does feel a sense of obligation as an artist to shine a light into the dark recesses of the past. “I do think that we have a responsibility if we have been given stories, or we are finding things out, to actually take them forward into the future,” she says. “It is always a case of negotiating the past into the present.” The truth will out.

Judy Watson: The Edge of Memory

Art Gallery of New South Wales

10 November—17 March 2019

This article originally appeared in the November/December 2018 print issue of Art Guide Australia.