Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

The Biennale of Sydney will be reopening from 16 June, with some venues opening from 1 June 2020. More information here.

Kim Williams and Lucas Ihlein are socially engaged artists. As a practice, socially engaged art has been going on for a while, since the 1960s at least, but it has been growing in popularity and garnering more and more critical attention. If you aren’t familiar with the phrase, Tate Modern offers this handy definition: “Socially engaged practice describes art that is collaborative, often participatory and involves people as the medium or material of the work.” Which is not to say that artists working in this field don’t also make actual stuff. Some of them do.

When I meet with the artists to talk about their latest collaborative project, Plastic-free Biennale, Ihlein, laughing, hands me a white sheet of paper covered in typed bullet points and scrawled notes. “We joke about how as artists what we do is develop Google documents and produce A4 sheets of paper for meetings,” he explains. “It’s one of our mediums!”

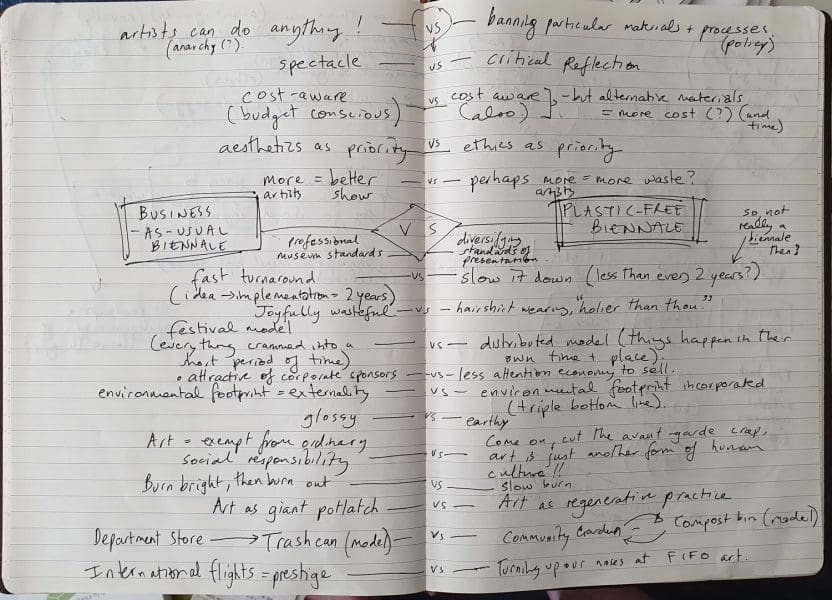

The meetings Williams and Ihlein have been going to recently are with Biennale of Sydney staff; the artists have been commissioned to help them facilitate their desire to go plastic-free. The Google doc I’ve been handed states upfront that “this is nigh-on impossible to achieve,” and asks, “So, how can we as artists work in this space where good intentions butt up against our inevitable failure?”

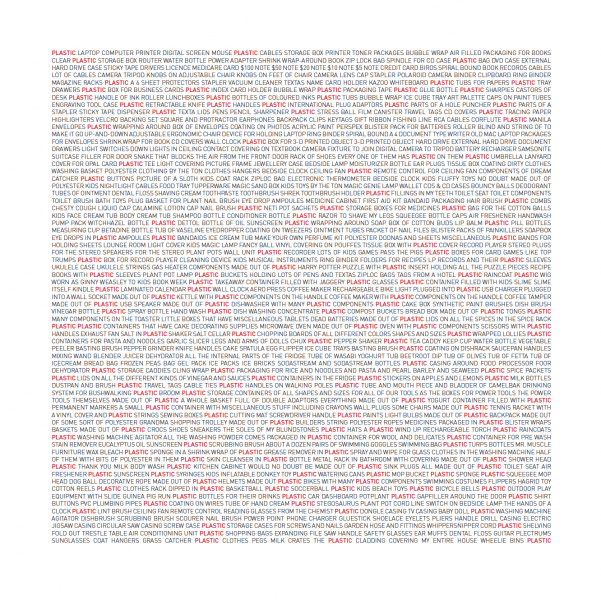

One way Williams and Ihlein deal with the inevitability of failure is to acknowledge it head on. And as artists they do this in ways that affect the heart as well as the mind. For example, explains Williams, they conducted household audits and itemised every single bit of plastic they could locate, then this information was laid out as a concrete poem: a monumental solid block of text that scrolls over not one but four A4 sheets of paper. The bulk of this text—its massive virtual weight made manifest in bold black type—is part of what gives this artwork its strength. “The concrete poem has had quite an impact on friends who have seen it,” she says. “It is horrifying.”

“That auditing process is powerful,” Ihlein adds, “because it is one thing to say, ‘yeah, it’s everywhere: plastic is ubiquitous’. But it is another thing to actually list it all out, because the list goes on and on and on. And after a while you are like, ‘holy hell.’ And that has an emotional effect.”

This punch in the guts is of course the power of art. But Williams and Ihlein don’t want us to be paralysed by the enormity of the mountains of plastic we are all surrounded by. As Williams puts it, “Plastics is a symbol of something larger, isn’t it?” The artists’ aim is to provoke conversations around broader topics of environmental sustainability and responsibility, rather than provide definitive solutions. “We’re just kind of swimming around in this material to see what might emerge,” Ihlein explains. “We don’t have the answers.”

And not having answers is actually one of the key strengths of their socially engaged practice. Williams and Ihlein are perhaps best known for Sugar vs the Reef—a long term project where they worked in collaboration with fellow artist Ian Milliss, as well as with sugarcane farmers Simon Mattsson and John Sweet, and various other members of the community in Mackay, Queensland. And they happily admit that when they started working on the project in 2014, they didn’t know a thing about sugarcane.

“I think part of our method is to not get fussed about not being an expert on the problem situation before we get into it,” Ihlein explains. “Actually, our ignorance is an asset! Because then you are in a position of having to listen, so the community that you are interacting with become the experts. And just listening in a very engaged way is very affirming for them.”

Up until this point, the primary community the artists have been listening to has been Biennale of Sydney staff. And by listening, acting as “productive irritants” as Ihlein puts it, and by using plastics as a symbolic starting point for wider discussions, they have already helped staff take a good hard look at their working practices. “I guess we have been trying to raise questions about what sort of responsibility does a biennale have,” Williams says.

And some changes have already been made. For example this year, on Cockatoo Island, the Biennale of Sydney is using recycled corrugated iron for temporary walls in lieu of brand new gyprock, and catering contracts for the opening events have strict no single-use plastics clauses. These initiatives may be small, but they are important. As Ihlein says, “They start to get into the DNA of the way that they operate; then they spiral out.”

And hopefully, visitors to Williams and Ihlein’s Plastic-free Biennale on Cockatoo Island will also get caught up in spiralling discussions and feel inspired to take actions, both large and small. The work, Williams says, “will be both complete and incomplete” when the Biennale opens to the public. Which means that while there will be evidence of their process on show, visitors will also be invited to participate in an evolving project. One way the public can get their hands dirty (or clean) is to join in scheduled dishwashing sessions at the café on the island, to help reduce landfill. Williams and Ihlein will also be running tours focussing on microplastics on Sydney harbour beaches.

As a socially engaged project, Plastic-free Biennale doesn’t consist of what Ihlein calls “a singular spectacular entity, which is the work.” Instead, it includes a wide variety of posters, several manifestos, videos (including a music video featuring the plastics concrete poem), an online platform, performances, talks, plastic nurdles and other artefacts, and, of course, A4 sheets of paper. But as both Williams and Ihlein acknowledge, Cockatoo Island itself is also part of the exhibition, a metaphor for our own beleaguered planet: a precious island in space, a vulnerable closed system.

Lucas Ihlein and Kim Williams

Plastic-free Biennale

Cockatoo Island

14 March—8 June

This article was originally published in the March/April 2020 print edition of Art Guide Australia.