Australia’s most famous portraiture prize, the Archibald, enters its 98th year with its ability to attract derision intact.

Some critics, such as blogger Eliza Underwood, continue to argue that the prize dupes the public into believing that the $100,000 honour represents the best of Australian art. Others, including John McDonald, sniff that the whole anachronistic affair should not be taken too seriously.

Given the record 919 entries this year (up from the previous record of 884 in 2014) artists are hardly shunning a prize that attracts saturation media coverage, launching and burnishing their careers. Its value lies in the attention a nation that idolises sport momentarily pays to art, a subject hardly normally threaded through its daily conversation. During the Archibald, art becomes a national group chat.

Outrage over winners, such as in 2017 when old guard painter John Olsen took a swipe at Mitch Cairns’s prize-winning portrait of his artist partner Agatha Gothe-Snape, invaluably fuels that conversation.

To complain about the merits of winners and whether their entries break new ground is almost beside the point; it is in the potential for audiences to be funnelled from the Archibald into surrounding exhibitions (thus improving art literacy overall) that the true long-term value of the perennial prize lies.

Archibald audiences that would not normally visit a gallery to see landscape painting might find themselves taking in the $50,000 Wynne prize, held concurrently at the AGNSW, likewise the $40,000 Sulman prize which is awarded for best subject or genre painting or mural project. They might also pay fresh attention to collections there or at the regional galleries hosting the Archibald tour in Healesville, Gosford, Muswellbrook, Moree, Bathurst and Coffs Harbour.

The Archibald and Wynne prizes are judged by the AGNSW trustees, so it is fair to ask what the board of trustees president David Gonski, deputy president Gretel Packer, and board members from fields such as aviation, medicine and private funds management know about art. But remember, there are two artists on that board: Ben Quilty, himself a former Archibald winner, and Quetta-born Khadim Ali. The Sulman, meanwhile, is judged by a single artist. This year it’s Sydney-based Fiona Lowry.

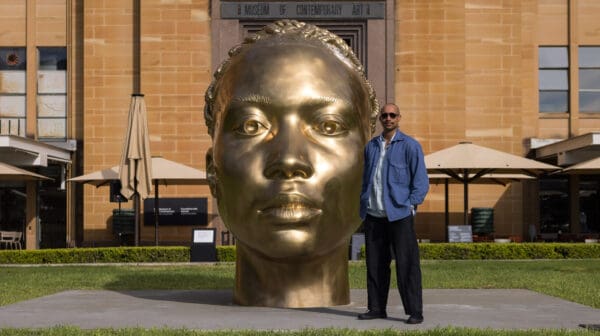

The Archibald is art for the public, as much about recognition of its subjects as it is about composition and execution, and the 2019 Archibald field succeeds in reflecting back to Australia the diversity of who we are today in a way that, say, white-skin obsessed commercial television and much of the mainstream print media often fails to achieve.

Among the 51 Archibald finalists, we see a painting of Professor Michael McDaniel, chair of Bangarra Dance Theatre – Australia’s only Indigenous major performing arts company, as defined by the Australia Council for the Arts – and another of the Sydney-based playwright and actor Nakkiah Lui, whose satirical works have effectively skewered white entitlement. Some of the numerous Indigenous finalist artist subjects have been painted by Indigenous artists: Aunty Esme Timbery sat for Blak Douglas; Vincent Namatjira painted Tony Albert; Thea Anamara Perkins depicted Christian Thompson.

We see examples of our migration success story: portraits of Kuala Lumpur-born Anant Singh, the Adelaide restaurateur of Punjabi heritage who helps the homeless; lawyer and diversity advocate Mariam Veiszadeh, whose family fled Afghanistan, posed like Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring; and the London-born, Ghanaian-Chinese actor, broadcaster, writer and DJ Faustina Agolley. There’s the writer and broadcaster Benjamin Law, and the artist Lindy Lee, both born in Queensland, both of whose work challenges our cultural preoccupations.

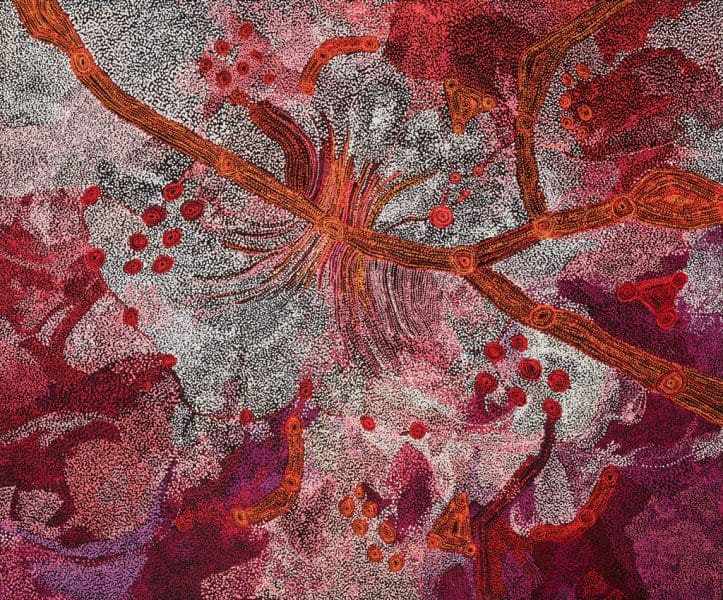

It is only natural that we respond to faces, but when we have had enough of those, there are the 29 finalists for the Wynne prize for landscape. McDonald’s criticism that the AGNSW turned the central gallery into an “enclave of Indigenous art” for this competition at the expense of non-Indigenous Wynne entries, thereby creating a “racially segregated exhibition,” needs to be seen in the context of the monocultural myths that pervaded the prize, first awarded in 1897.

As trustee and artist Ben Quilty pointed out recently when interviewed at the Sydney Writers Festival, Indigenous artists’ work has been under-represented even in the Wynne’s more recent years.

In that sense, the gallery’s emphasis on Indigenous entries today in the Wynne prize is a crucial corrective, much like the advent of the Sydney Modern redevelopment in 2021, which will necessarily place Australian Indigenous art front and centre, drawing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art out from the current shamefully neglectful exhibition space in the gallery’s basement.

This year, Tony Costa won the Archibald Prize for his portrait of Lindy Lee. The Sulman prize was won by McLean Edwards with The first girl that knocked on his door and Sylvia Ken was awarded the Wynne for Seven Sisters. Tessa MacKay won the Archibald Packing Room Prize with her portrait of actor David Wenham.

2019 Archibald, Wynne and Sulman prizes

TarraWarra Museum of Art

14 September – 5 November

Gosford Regional Gallery and Arts Centre

15 November– 12 January 2020

Muswellbrook Regional Arts Centre

24 January – 8 March 2020

Bank Art Museum Moree

20 March – 3 May 2020

Bathurst Regional Art Gallery

15 May – 28 June 2020

Coffs Harbour Regional Gallery

3 July – 16 August 2020