This year NAIDOC week starts with Tjungunutja: from having come together, an exhibition that charts how Papunya, a camp 240 kilometres north-west of Alice Springs, established by the Australian Government in 1959, gradually became a melting pot of ceremony and culture among Indigenous peoples exiled from their homelands.

In 1971 Geoffrey Bardon arrived at Papunya in a Kombi van stocked with paints, brushes, canvases, film and movie cameras. Steve Dow spoke to Pintupi artist Bobby West Tjupurrula, Luritja elder Sid Anderson, and Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory curator of Aboriginal art Luke Scholes. He found out that there is more to the history of the Western Desert art movement than this well known story. And together they discussed the significance of the 130-plus paintings and cultural objects on show in this landmark exhibition.

Steve Dow: Bobby, you’re the son of the late Freddy West Tjakamarra, a Pintupi artist who started painting in 1972. The Pintupi were the last to come into Papunya from the desert. Was it difficult, being among strangers on different country?

Bobby West Tjupurrula: Everyone was different, yeah. Government was always trying to move people. They used to send a truck from Papunya, load them up real good. They brought us from the bush into the settlement. We knew it was overcrowded, you know?

SD: How did you feel living with all these different language groups?

BWT: We had to share culture with a lot of people, with a lot of strangers. It didn’t matter. As long as they wanted to live in Papunya, with tucker, flour and sugar. Because at that time, they were getting rations, right? I was only a little boy, and my sister a baby.

SD: So all these different groups started sharing ceremony for the first time?

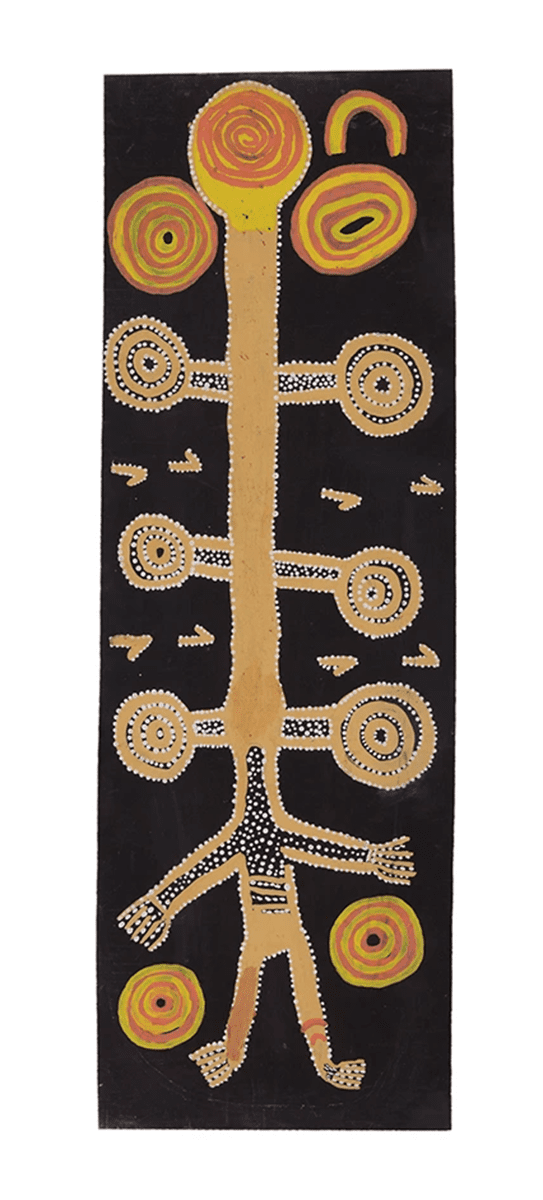

BWT: Yeah, we started coming together: Luritja, Pintupi, everyone. They were all the same. They challenged one another, and the Tjukurrpa [Dreaming] came together.

SD: Luke, I understand the first Papunya paintings were sold in Alice Springs in 1971, not by artist’s name but by painting size. When were the first Papunya paintings made?

Luke Scholes: My catalogue essay confronts the popular myth of Papunya. The story of Sydney art schoolteacher [the late] Geoffrey Bardon, is well known, that he came along and encouraged people to adopt these new materials.

But he came upon an already existing art movement. You had Western Arrernte artists from Hermannsburg who had relocated to Papunya; Albert Namatjira lived the last few months of his life in Papunya.

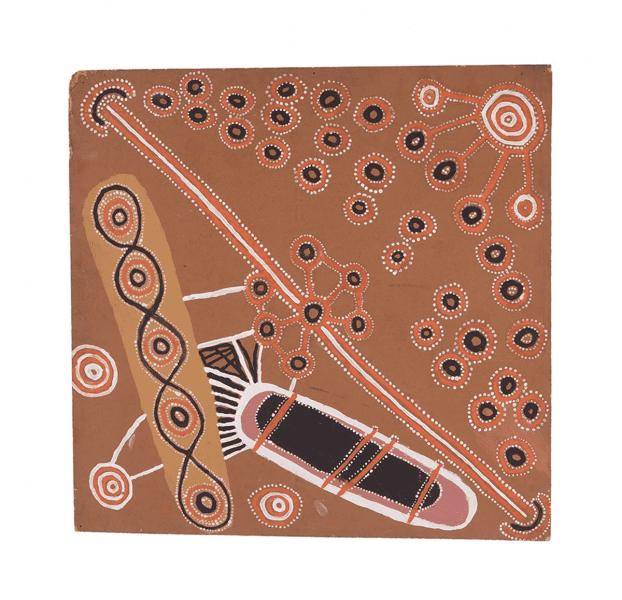

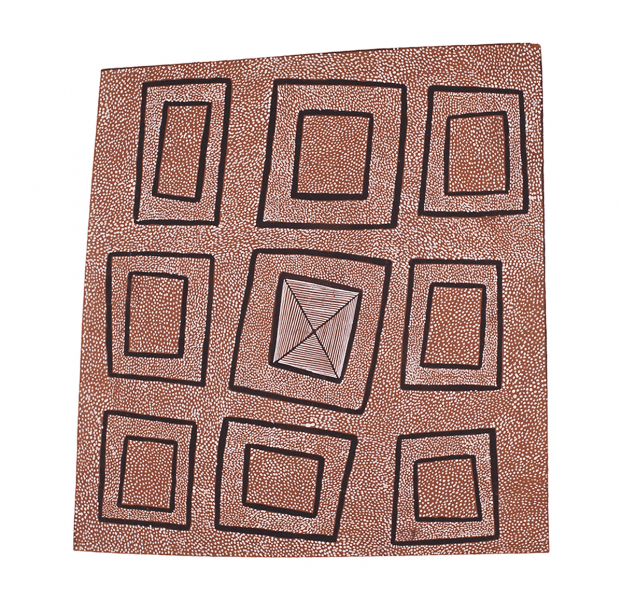

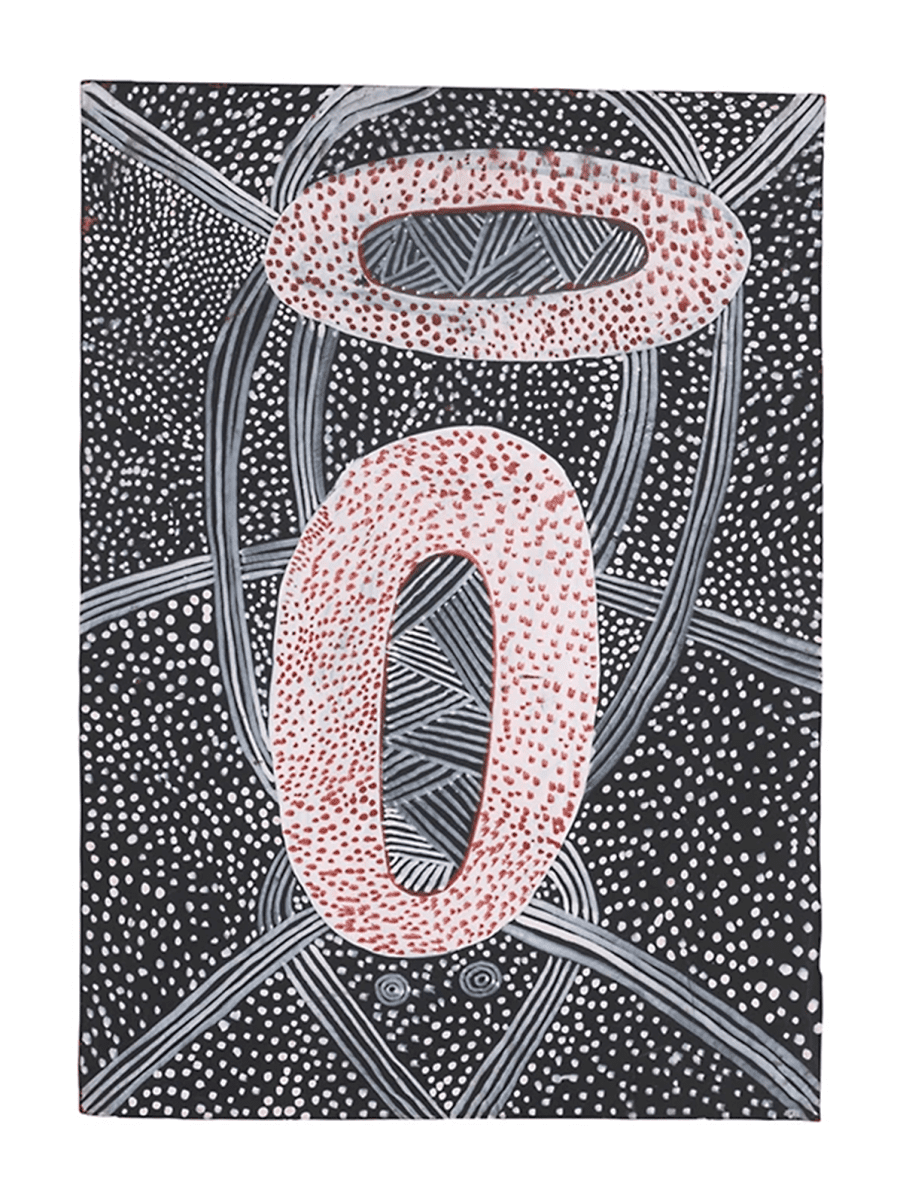

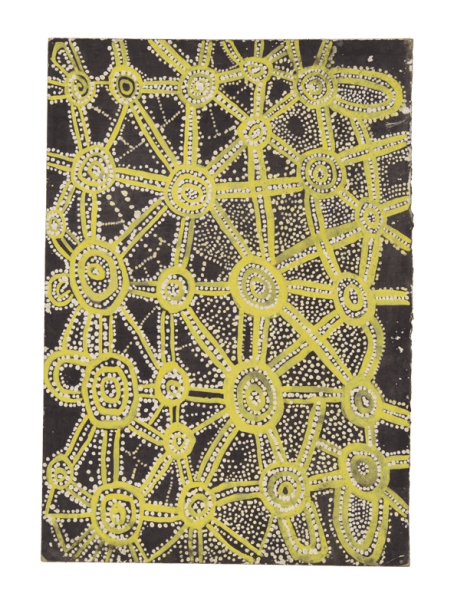

The painting style (to reduce it crudely, the circle and path) emerged out of Papunya probably earlier than 1971. There’s evidence of a group of artists occupying a disused settlement office from late 1969, creating boomerangs, shields and spears, and they would sell these artefacts to the Papunya Social Club, a roadhouse community store.

There was a good relationship between artefact makers and watercolour artists. The artists started painting designs previously used on shields and bodies onto pieces of scrap lumber.

SD: This exhibition covers the first couple of years of Papunya art, and I believe Long Jack Philipus Tjakamarra, one of the movement’s founding artists, born circa 1932, has been involved in its curation?

LS: Yes. Long Jack was a close friend of Geoffrey Bardon. Long Jack, Billy Stockman Tjapaltjarri and Kaapa Tjampitjinpa (the most entrepreneurial of the artists) used to gather in the back of the classroom at Papunya School and do paintings there, among others.

SD: Sid Anderson, as a Luritja elder now, you’ve said you weren’t really aware of the paintings being made, that you were busy back then as a young fella running around chasing horses. What was it like to help select these artworks?

Sid Anderson: It was a good experience. When I was young, I didn’t see the paintings. The old men were doing the paintings of their Dreamtime countries. There were Arrernte people, Anmatyerr people, Warlpiri people, Luritja people, Pintupi people, all together and they were sharing Dreamtime with their paintings.

The first time I saw them, the spirit just came into my body and made it lighter for me to understand the paintings.

SD: Did you have lots of debate about what to include in the show?

SA: I spoke with Warlpiri artist Michael Nelson Jagamarra and Long Jack. The old people took me and Bobby together to have a look at the paintings, to know which ones were not sacred and could be put on in the show.

Luke Scholes: The collection had to go through consultation managed by the Aboriginal Areas Protection Authority, because a number of paintings depict ceremonial scenes that aren’t appropriate for [Indigenous] women and children to see, 63 were deemed not appropriate for exhibition. So they won’t be included.

SD: Inappropriate for non-Indigenous people to see, too?

LS: Non-Indigenous people, we are generally called “ngurrpa,” a Luritja word that means ignorant, in the sense that you have no knowledge of it. We’re so ignorant of the dangers the designs represent that they are not dangerous to us.

SD: Why were only men from Papunya exhibiting art initially?

LS: It’s a very patriarchal society, and artefact making was a male activity. That’s not to say women didn’t manufacture ceremonial objects as well, but it really does underline the connection between the transference of designs, once painted onto “kutitji” like soft beanwood shields, onto pieces of timber often then shaped like men’s ceremonial objects.

SD: Is it true that the first Papunya show in Alice Springs in 1971 caused distress because sacred information was shown?

LS: Elements of that are certainly true. That gallery was asked to alter the exhibition to ensure no offence was caused. The local paper in its coverage probably over-emphasised the reaction: the story about rocks and spears being thrown [in response] might have been an exaggeration by the journalist at the time.

SD: So, did dots then come to dominate the pictures not just for their Dreaming symbolism but also because that style gives away less sacred material?

LS: That’s a little bit of a furphy. We have 16 of the first 27 paintings transported into Alice Springs [in 1971], and the majority are heavily dotted. The artists were dotting the paintings from the start. Quite often, dots were also used to punctuate painted ochre designs on bodies.

That’s not to say that artists such as Clifford Possum and Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri and others later didn’t use dots to mask some things about their paintings.

SD: Bobby, how important was Papunya to Aboriginal art generally? Did the ceremonial sharing at Papunya allow Indigenous art to spread?

Bobby West Tjupurrula: Yes. That was very important. That was the way they wanted to keep their culture, and teach their young ones: their sons, their nephews, their cousins, you know? That way, everybody can recognise they went through the Tingari [cycle of Dreaming songlines]. We came together and shared the culture.

The art is really important to my children. It’s the only way to keep the culture and the law together.

Tjungunutja: from having come together

Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory

1 July 2017 – 18 February 2018