Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

It’s an interesting proposition to put Tina Stefanou, an artist engaged with diasporic and working-class experiences, into the hallowed halls of the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA)—a space of grand vision that I imagine is accompanied by many bureaucratic entanglements, given its physical and cultural scale. When asked how one approaches such an invitation, she admits she must reckon with “what it means to be the belle of the ball”—a challenge for an artist deeply grounded in collaboration.

Stefanou works to dissect class structures, in opposition to and in conversation with bourgeois realities. As the artist notes, “working within the working-class commons, living in working-class ways, my default isn’t the educated bourgeois. I’ve moved into these spaces through the arts. My work is community-driven. If you are an artist existing within community, you need to honour it.” For Stefanou, community is the work and the work takes place outside of the gallery. This will be exemplified in what the artist refers to as the “living-bibliography” accompanying the exhibition You Can’t See Speed at ACCA—an extended list of everyone involved, without hierarchical bias.

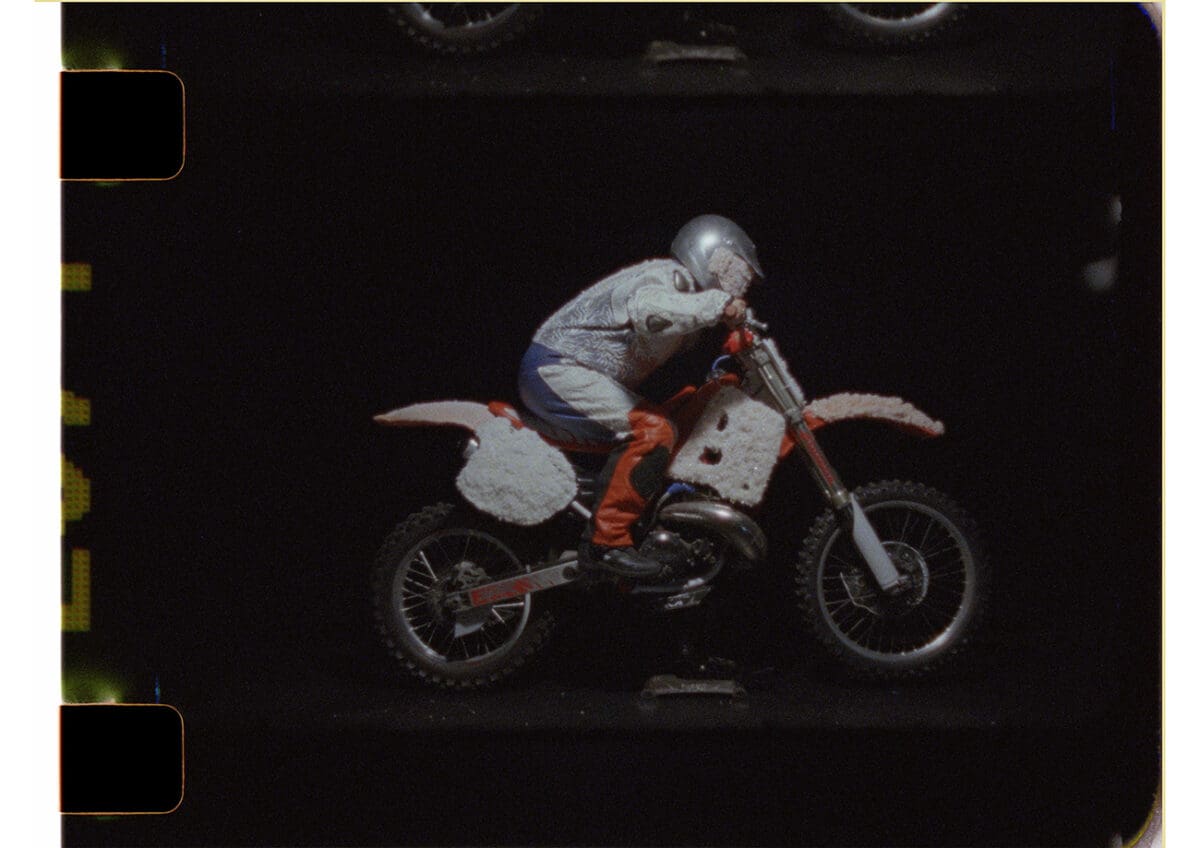

The main commission centres blind motorbike rider Matthew Cassar. Stefanou was curious to understand how Cassar navigated riding, in relation to her prior work with horses and neurodiverse riders. Through many meetings, the two found shared understandings and differences. Cassar comes from a Maltese working-class upbringing, synonymous with the ideologies and behaviours of ‘masc’ culture—that which centres what may be deemed as masculine. Stefanou comes from similar cultural spaces, yet has moved into urban-educated realms with different ideologies and concerns. When traversing classes, Stefanou reflects, “there’s things you try to escape when attempting to ascend into different economic or cultural spheres, but sometimes this is to your detriment.” Cassar’s generosity to openly meet arts realms with authenticity is what makes this work possible. This is an allegory for Stefanou’s dedication to meaningful engagement when working through socially driven practice. Value resides in peer-to-peer support and an openness to find peers in unfamiliar places.

This central work—a video of Cassar riding while instructed via earpiece by his coach—is but a magnificent remnant of the ‘real work’. The real work is Cassar and Stefanou’s relationship; it’s the exchanges between Cassar and his coach; it’s Cassar’s meeting with queer arts workers. The work speaks across “ideologies and divides where all parties are equally confronted.” Stefanou recalls, “Matthew had to understand there are things he’s normalised that need to be addressed—certain rhetoric in his sphere that may be OK, but when taken into a new sphere may be offensive. Through clichés of dirt-bike imagery, I’m working with his experience—that of a 48-year-old cis, blind, working-class man—and am problematising that through my working-class, female, ethnic gaze.”

Through Cassar’s experiences of blindness, this work provides an example of how non-seeing people can reimagine the world. Cassar recalled to Stefanou how he built a fish tank, so he could imagine the fish inside. This exemplifies Stefanou’s task: to create a cinema by other means. What does it mean for someone like Cassar to have an almost erotic relationship to his motorbike, on account of his mode-of- seeing? These exchanges work to flip attachments we have made to certain aesthetics, to certain identities. A partial response to this can be found through the exhibition’s audio captioning. Cassar speaks his film into a more surreal vocal-language, describing the feeling of it. Stefanou’s family narrates the films they are in. Films of pony-girls are met with their own captions. Stefanou’s mother-in-law, Julie, responds to Miming for Mines: You Can’t Hear Faith (2022)— a document of herself, a retired deaf nurse, miming songs of faith at the Loy Yang Power Station in the Latrobe Valley. Having curated this work into an exhibition at MILK Gallery in 2022, I watched it countless times and became enraptured with Julie’s movements—what seem like acts of deep listening despite the inability to hear, or as Stefanou calls it, “an Anglo working-class butoh.” Regarding Julie’s new offering, Stefanou notes, “As a deaf person, her voice is affected, already non-normative. This is the site of artistic modality. I haven’t invented it. It’s Julie.”

Horse Power (2019), a film by and with horses, will be shown concurrently to You Can’t See Speed in Thinking together: Exchanges with the natural world at Bundanon. Stefanou visited rescued horses, caring for and singing to them.

Responding to her voice, the elderly horses became part of her life for almost a decade. The horses stand as allegory for Stefanou’s ‘workhorse’ grandmother and thus are interlinked with stories of migrant labour. Stefanou notes that exhibitions regarding ecological sustainability often lack the inclusion of class discourse. In a time when certain aesthetics give undeserved permission for artworks to be seen within the ecological field, it’s Stefanou’s sustained relationship with the horses, far outside the bounds of the filmic work, that enables it to sit confidently in the field of true ecological practice.

The success of Stefanou’s work relies on the energy required for socially engaged, or in the artist’s words, “socially endangered” practice. She sees these exchanges as “doing what should be the work of the state—providing services for connection, beyond the everyday. …The question is: are we going top-down, or allowing ourselves to build from the ground up?”

You Can’t See Speed

Tina Stefanou

Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (Melbourne/Naarm VIC)

On now—9 June

Thinking together: Exchanges with the natural world

Bundanon

(Illaroo/Dharawal and Dhurga country NSW)

On now—8 June

This article was originally published in the May/June 2025 print edition of Art Guide Australia.