Poetics of Relation

Tender Comrade, currently on show at Sydney’s White Rabbit Gallery, creates a new vocabulary of queer kinship by reimagining the relationship between artworks, bodies and space.

Andy Butler, Lisa Hilli and James Nguyen each engage with institutional collections and the power dynamics that shape public culture. Their works are informed by personal histories of migration from Southeast Asia (Butler and Nguyen) and the Pacific (Hilli), and they have a mutual crossover of experience—being one generation away from the village, they now navigate spaces founded on exclusion and prestige, like universities and museums.

Collective Unease is an exhibition of new commissions by the three artists, showing at the University of Melbourne’s Old Quad—a gallery space located in an original university building, constructed in 1853. The artists responded to the University collection—which contains objects and artefacts from the university’s history, art and culture, sport and medicine— drawing out the complexity of the institutional history. Here, the artists talk together about why and how they work with collections, what they’ve created for Collective Unease, and what it means to keep your knife sharp when carving out paths in spaces never meant for you.

Lisa Hilli: I started working with collections accidentally. I didn’t even know collections existed until 2010. I was so naïve, and that just speaks volumes about who collections are for. This auntie from Bougainville told me, “Oh, you should go to Sydney! There are these things in the museum and there’s this woman there called Taloi Havini.” A Pasifika artist, Taloi worked at the Australian Museum years ago.

[I went to the Australian Museum and] I looked at their three levels of storage, and it blew my mind. I’m one generation away from the village in PNG [Papua New Guinea], helping out my mum with social security forms, interpreting things for her. And here’s this institution that’s been collecting artefacts from home since the 18th century. And I was just like, “Why, why, why?”

James Nguyen: There’s a creepiness to collecting. As our families left their home during moments of conflict or upheaval, there’s two parallel paths. One is escaping to the West, out of the village, looking for a better life—we leave with nothing and resettle. But then, magically, through these Western collections, the people who are displaced end up living a few suburbs over from the museums holding objects relating to the places they were displaced from. There are these objects that are part of you and your history, but they’re sitting inside archival boxes.

It’s so weird how they separate the humans from the objects; they separate the messiness of migrants and refugees from these objects. Institutions have this power to control the narratives over these objects.

Andy Butler: I guess that’s why I’m drawn to collections. There’s such a friction between their desire for equality and justice and change, and the inability of the collecting structures to do so. This is a good time to talk about the work in Collective Unease. Do you want to start, Lisa, talking about Meg Taylor and your project Birds of a Feather?

LH: I’ve made five banners focused on the first woman from Papua New Guinea to go through the University of Melbourne: Dame Meg Taylor. The Old Quad is such a historically loaded building. I was previously a Museum’s Victoria employee, so knew that the University and the Melbourne Museum were historically intertwined. But then I found out that the Old Quad was where the collection all started, where they displayed artefacts. Dame Meg Taylor from PNG studied in that building too, but was never written into history. No reference to her at all having graduated.

AB: While James and I have heard about Meg Taylor, can you give a sense of how wild it is that she was excluded from University of Melbourne history?

LH: Meg was a trailblazer for PNG women. She graduated from studying law in 1973, still under the White Australia policy, while PNG was still an Australian colony. Then she went off to Harvard. She was the first woman to be admitted to the bar in Papua New Guinea, and the first Papua New Guinean woman to be admitted to the bar in Australia. She was the first ever female secretary general of the Pacific Islands Forum, which is one of the most important inter-governmental political bodies in Oceania.

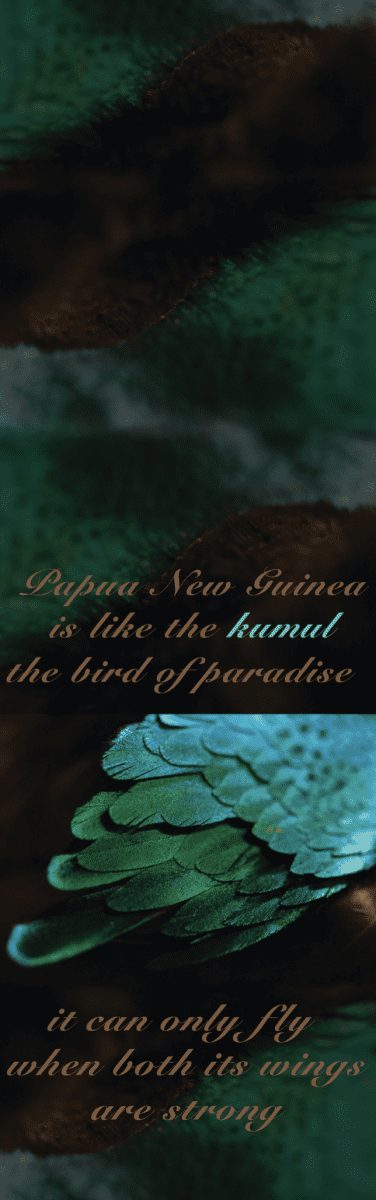

For Birds of a Feather, I wanted to see birds of paradise feathers everywhere and present them in a way that Papua New Guinean people understand them—the connection we have to birds of paradise, culturally, spiritually, as a form of body adornment and identity. That’s my understanding of birds of paradise, not these collection taxonomies and scientific names that separate animals from humans.

JN: The way you talk about those feathers, Lisa, reminds me of something like tartan. As an outsider you don’t realise that woven into it are stories and family and history. It’s so much more than just the aesthetics of it. It’s not like a David Attenborough documentary!

LH: That’s right. It’s exactly that. I wanted to go beyond that surface level, against the reductive portrayal of people and animals from PNG. Which is why I didn’t want to include any images of Meg herself, but just her words. One of the key works for me is Mek. It represents Meg because local people refer to her as “Mek”, which means the bird of paradise with long black feathers. So that bird is her! And that’s the bird that is represented in that fabric panel.

JN: l love how your work really gives voice to the academic achievement, and attests to the power of Meg through her words. But also thinking about how linguistically her people call her Mek, that’s knowledge that isn’t understood by the academy because they never valued it. It’s cultural knowledge that some people will never have real access to. The work is speaking in a covert way to people in the space who’d culturally understand that reference.

LH: Thanks, James. You’ve articulated that really well, in terms of what some covert aims are of that work.

AB: Do you want to talk about your work, James, An Australian National Song?

JN: I was interested in the period of Australian federation, with this vision to create a white paradise and eradicate everything else. There’s some super grandiose music to celebrate that period. And the University had a music collection from that era.

I found this new song for Australia, celebrating the vision of a white utopia. Then, I worked with other Asian-Australian musicians who are a lot better than me! We all played violin in this work, using a very Western instrument to detune the music. As we were playing we improvised, like some musicians pulled their violins apart, changed the bridge, rubbed violins together—things you’re not meant to do within the confines of an orchestra. It was like we could use this music as an excuse to play, but with an edge of retribution to it. It’s kind of like trolling.

AB: I love the playfulness. It really underpins so much of your practice, James. Even though the things you’re looking at are pretty dark, you bring so much humour and joy to your work, while hanging out with friends.

JN: Well, our parents and ancestors were exposed to so many unspeakable horrors, violence and oppression. So they’re sometimes considered a bit ‘crazy’ or whatever. But they survived, and they retained this sense of humour.

But now we have the privilege of entering these spaces, because we can speak in a certain way, because we can weasel in through art. I find if I focus on that horror or trauma, you end up being trapped. Despite not belonging, being ostracised, and being crushed, some of our people that came before us thrived.

They stood in their power. Like Meg Taylor, you know? And same with us. I think we can find fun and joy and hope in that.

I think that’s what your work speaks to, Andy. It’s this thing of elation; every time I see it, it lifts my spirit. It’s so hilarious and playful and human. It’s like whatever is thrown at us, we can survive and thrive.

AB: Thanks, James. That’s so nice! With my work The Agony and the Ecstasy, I was thinking about the complexities of hope, joy and optimism. You can feel like such a fish out of water in these spaces [universities], you know? I studied in that very building, Old Quad, doing my Honours in Philosophy. And it’s this disconnect where you feel so proud that you’ve achieved the working-class migrant dream of going to a prestigious institution, but then you get there and the veil drops and it’s this bizarro world.

I did competitive ballroom dancing as a kid, and there’s some crossovers with competitive cheerleading. There’s makeup and pageantry, and while it’s kind of misunderstood as a team sport, there are these micro-communities of care and support that are formed in gyms.

For my video work, I spent time going to Melbourne University Cheer and Dance training sessions. What really jumped out at these sessions was the sheer athleticism: the grit, the sweat, the intense teamwork, the months and months of training and body conditioning that goes into this two-and-a-half-minute routine that’s a distillation of uplifting energy.

All the athletes are current students of the University, and there’s this kind of ‘Gen Z energy’ with a desire for social transformation, for something that’s different from the institutions and world we’ve inherited. There’s a fluency in talking about equality, the climate crisis and things like that.

It’s a weird position to be in. We’re embedded in these spaces that have such dark histories that we’re trying to change. I’m still figuring out how to navigate that tension, I think a lot of people are. It’s like from that diasporic position where you don’t feel like you belong anywhere.

JN: That sense of belonging, Andy, I feel as I’ve gotten older, I’ve stopped giving a shit. I think what you’re describing is about more than just decolonising or whatever—it’s a deeply human experience of trying to find your place in the world.

You perform a particular way, a particular version of yourself in these institutions to survive and thrive, to get credits or distinctions or scholarships or whatever. But once you learn to speak in a particular way, or think in a particular way, you become severed from your family, and your “culture”, whatever that is.

So, I think it becomes much more about—how do you find a sense of belonging in any particular moment in time, or find joy and happiness in your own voice at any particular moment, and carving out and creating spaces for other people.

LH: I completely relate to what you’re saying, James. I don’t really ask that ‘belonging’ question anymore. It’s about carving out spaces for others who have similar experiences. I resonate with Meg Taylor so much for what she carved out for a lot of women like me to follow.

I have this mantra about how you’ve always gotta keep your bush knife sharp. In PNG you live in a jungle, so you’re cutting pathways through this grass. It feels like now in the wake of people like Meg Taylor I’m able to carve my own pathway if I keep my knife sharp, and carve out a space where I find some sense of belonging. There’re moments where you can find a space for yourself and for others following you.

Collective Unease

Andy Butler, Lisa Hilli and James Nguyen

University of Melbourne, Old Quad

Until 2 June

This article was originally published in the January/February 2023 print edition of Art Guide Australia.