Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

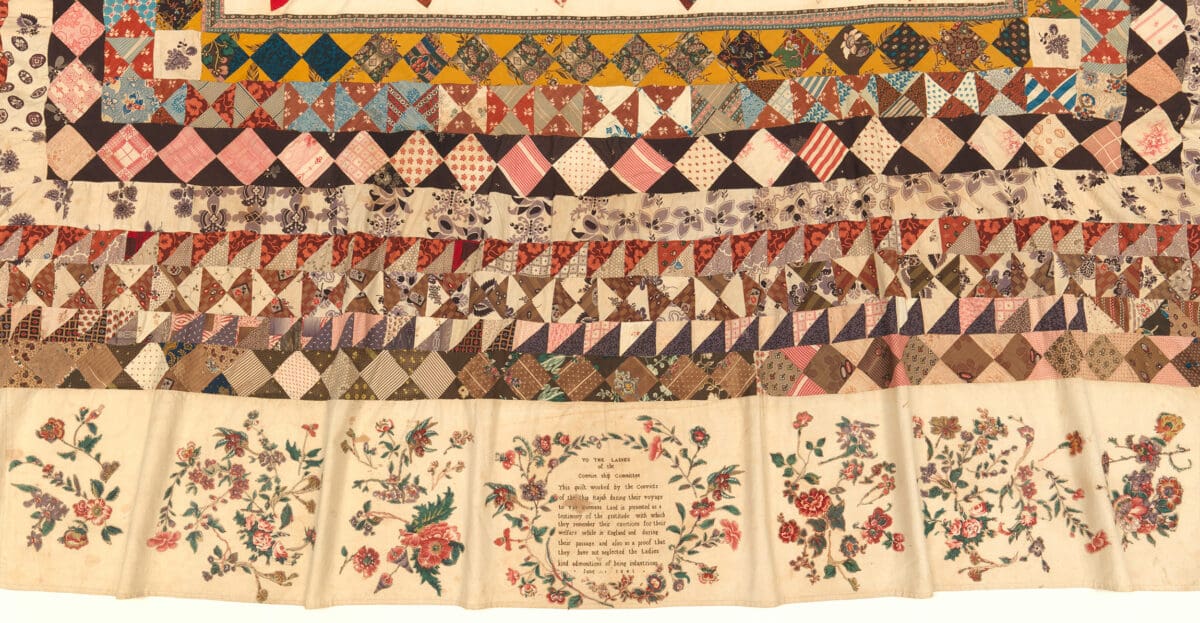

The Rajah quilt is one of the National Gallery of Australia’s most requested items but it’s rarely on display. “Textiles are incredibly easy to fade,” says the gallery’s Australian art curator Simeran Maxwell. “The structure of The Rajah quilt also means, unfortunately, it’s safest in its box.” The large quilt was made in 1841 by British convict women during their three-month journey to Tasmania on board the convict ship the Rajah. Visitors continue to make bookings to see it, but Maxwell says even displaying it in the study room is a challenge. The tables there are just too small to have it out all at once. “But there’s no point having things we don’t show,” she says.

The famous quilt is finally getting another day out in A Century of Quilts. The exhibition presents 22 quilts from the NGA collection, made from 1840 to 1940, and uses these textiles to trace shifting cultural identities. The Rajah quilt is the centrepiece, and will be supported in a purpose-built angled display to allow the details to be seen. “It’s amazing what they were able to achieve,” says Maxwell. “A rocking vessel, with no adequate sewerage, space, light or air? You’ve got to think about the women who made this.”

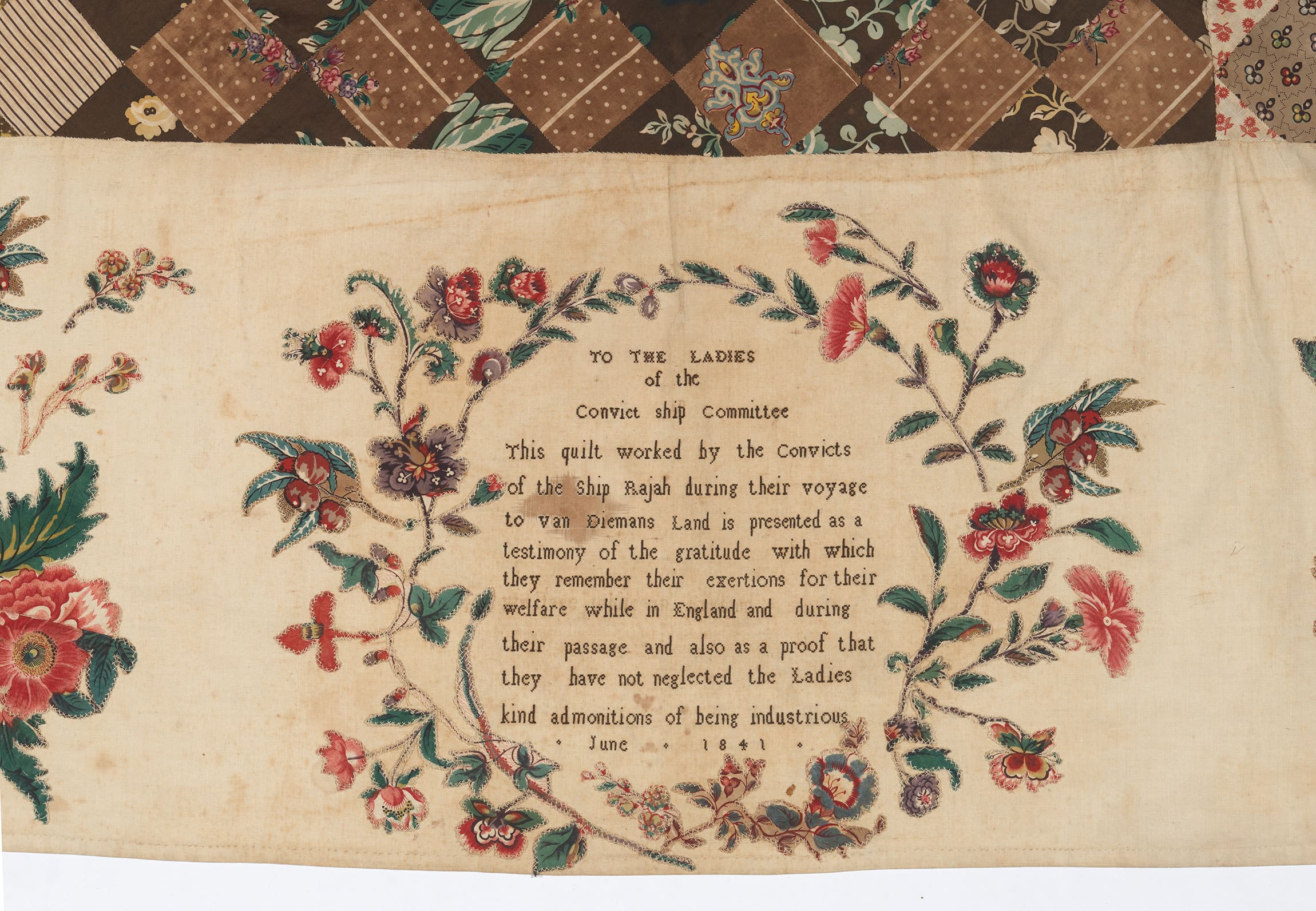

Some had experience in tailoring or needlework but others didn’t. There’s a variation of skill across the quilt, and the odd pinprick of blood too. At the bottom, the women embroidered an inscription thanking a British welfare group for their exertions supplying materials, and naming the quilt proof they have not forgotten their “kind admonitions” to be industrious. As a project, the large quilt was partly about developing the women’s skills and future prospects, but it was also a moral lesson about idle hands and devil’s workshops. “What you don’t see with a picture on a screen is the detail of all these different textile patterns and combinations that these women chose and juxtaposed against one another,” Maxwell says. “What really draws me into this work is the beauty.”

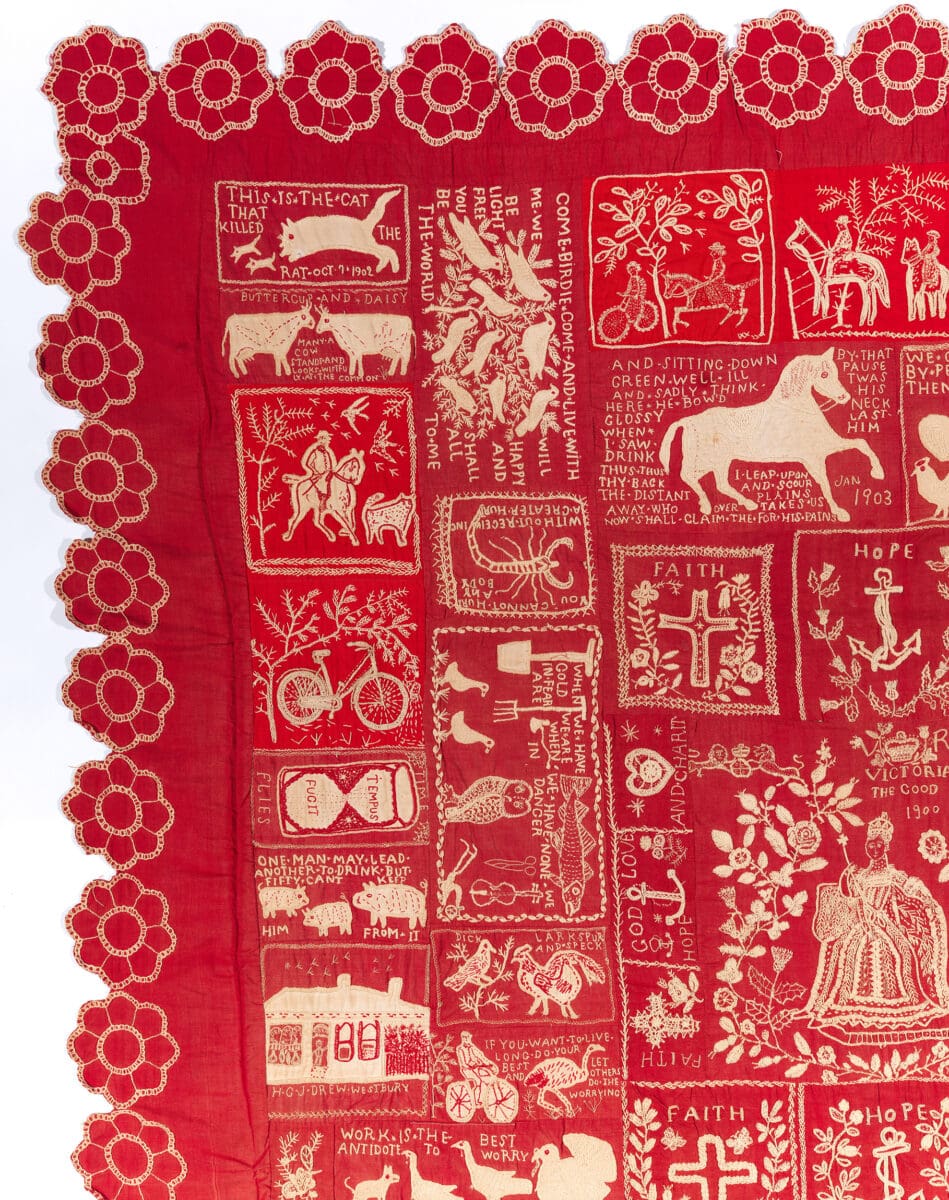

For Maxwell, textiles like this provide a “tangible link” to the past. The earliest pieces in A Century of Quilts speak to the firm hold of British culture and ‘Rule Britannia’ thinking. Even in The Westbury quilt, made by the Misses Hampson around the time of Federation, there is a central image of Queen Victoria. But with the move into the 20th century, there is “less Mother Country, more of what it’s actually like to live in rural Australia,” Maxwell says.

The pieces in this exhibition were typically made by women and small family groups living in relative isolation. “This was something they did to fill their time, entertain themselves, make their home a beautiful place, or give to friends,” says Maxwell. Some were clearly driven by poverty and necessity, “but they did it in such a beautiful way. They didn’t have to, but they chose to make incredible works of art.”

One is made entirely from ribbons won at rural livestock shows—a record of years of work and pride. Mary Jane Hannaford’s quilts and wall hangings, made in the early 20th century, show a remarkable realism and interest in the passing of time. Maxwell finds the later arrival of modernist aesthetics particularly curious. “These women often would not have been exposed to abstract painting or abstract art. This was something that came from within.”

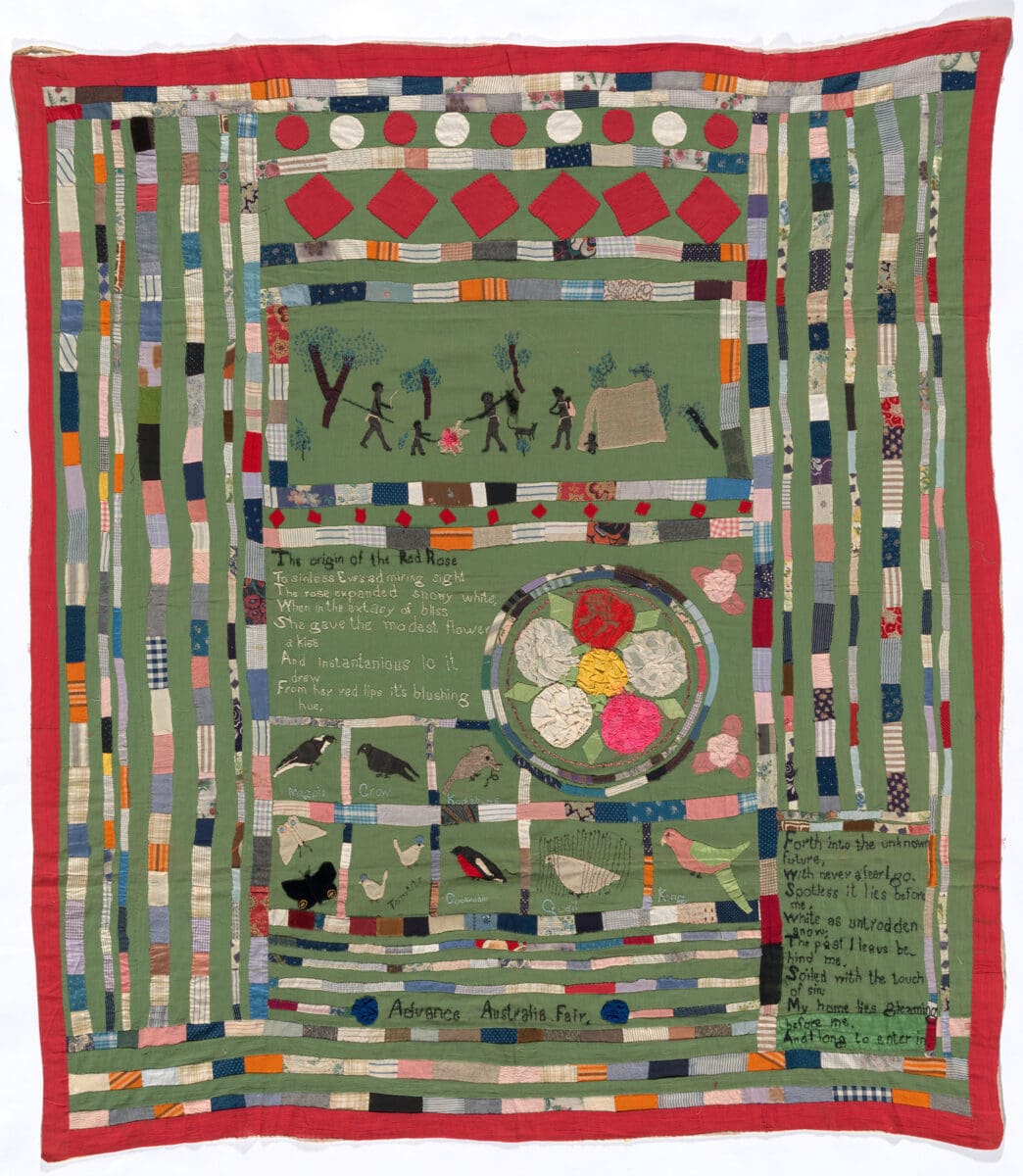

A Century of Quilts is mostly a story about key early curators who believed “folk art” had a place in a national collection, yet there are gaps in the stories that can be told with these pieces. While Mary Jane Hannaford’s Advance Australia Fair quilt and wall hanging, c1910-1925, includes a rare depiction of a First Nations family group, Maxwell knew it couldn’t be the only representation. As she says, “these white women…were not the first people in Australia making quilts. That history goes back further.”

She acknowledges the difficulty of conveying First Nations histories in a collection exhibition like this. “Unfortunately, the gallery doesn’t own a historic possum skin cloak,” she says. “There are only six in the world that we know of, and only two of them are in Australia.” Possum skin cloaks were carried through life. They were progressively extended, marked with records of family and country, and often worn at burial. The two cloaks that Maxwell refers to are held by the Melbourne Museum and their influence has been substantial in reviving possum skin cloak making in Victoria. A Century of Quilts picks up on the work done by artists Treahna Hamm and Lee Darroch, who have been instrumental in reviving knowledge around how these cloaks were made. The exhibition includes designs for the garments, as well as a child-sized cloak made by Hamm in 2005, which is displayed on a mannequin so that it can show how they were worn. It is a quiet but important curatorial decision. As Maxwell says, “You need to understand the context of how textiles exist, and were meant to exist in the world.”

A Century of Quilts

National Gallery of Australia

(Kamberri/Canberra)

16 March—25 August