Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

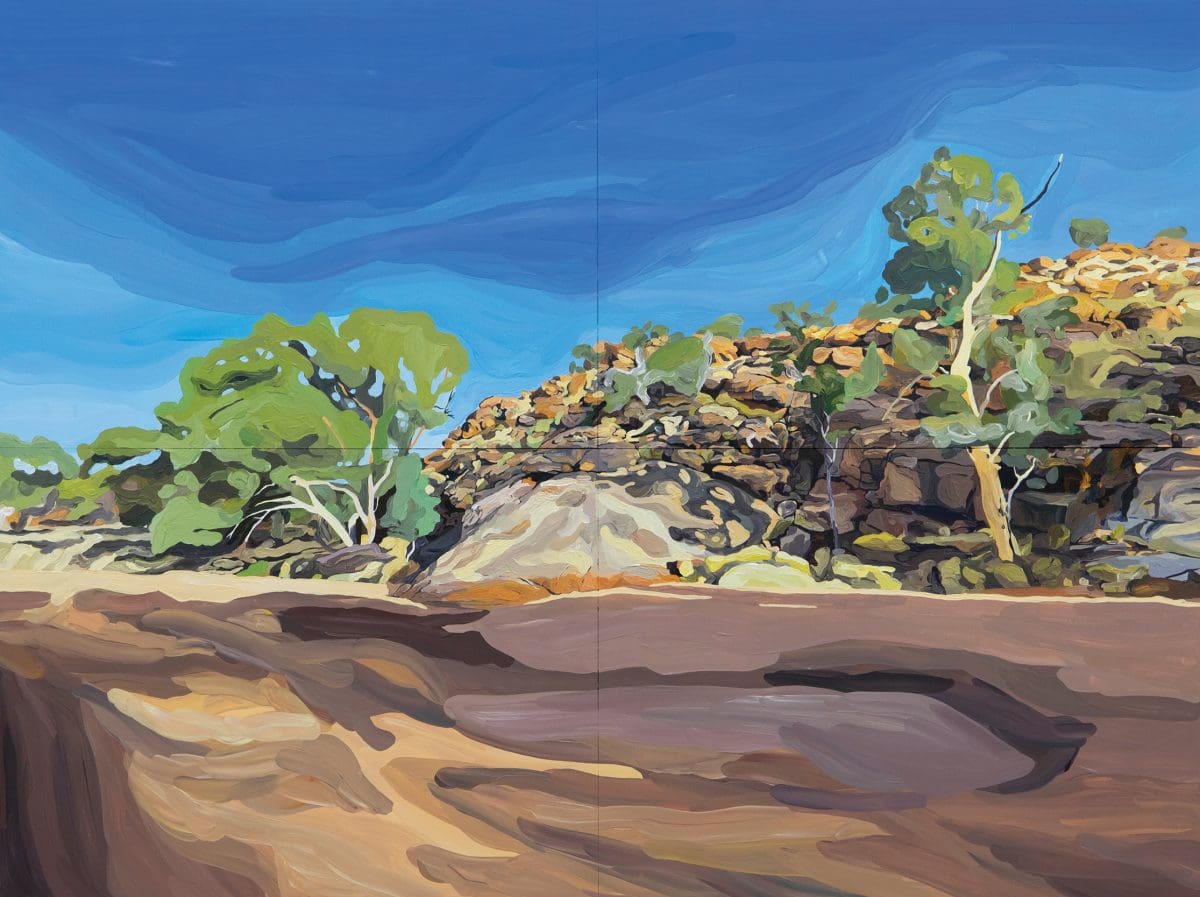

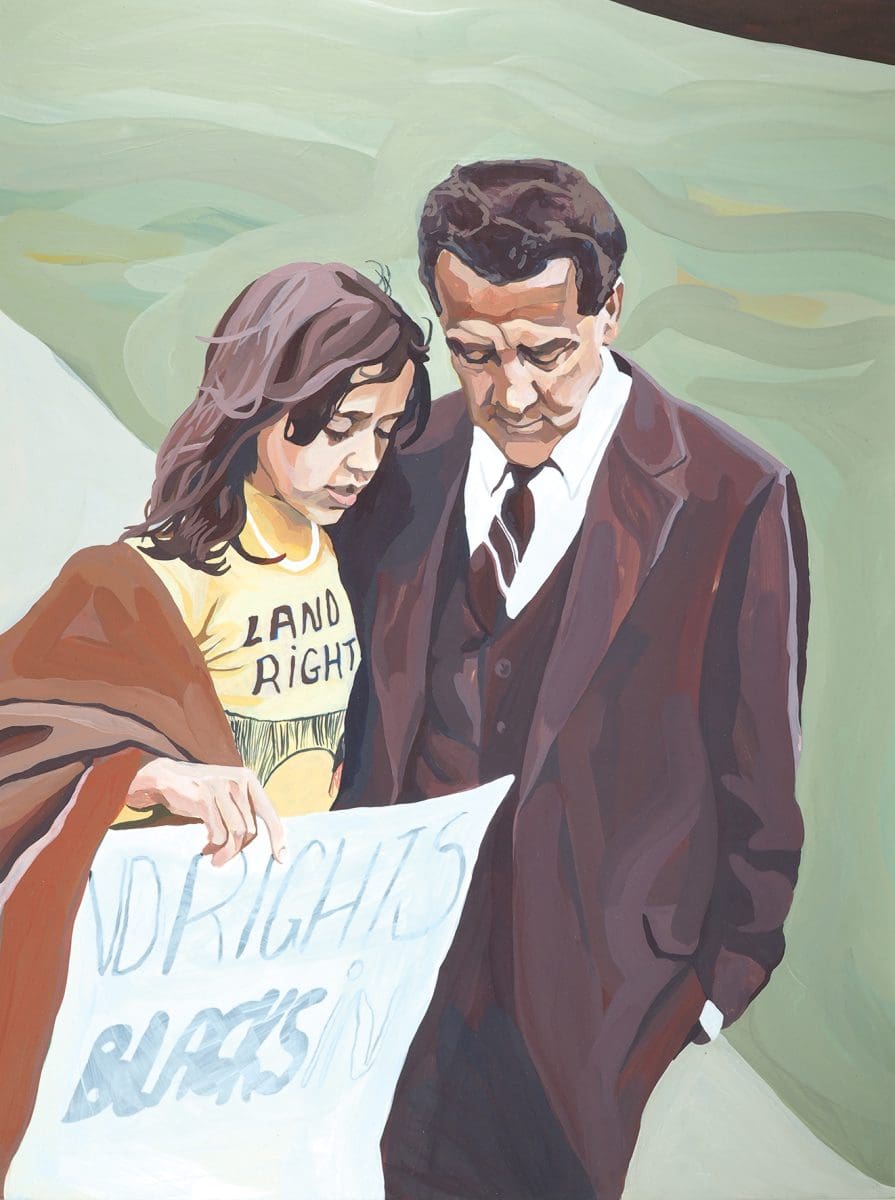

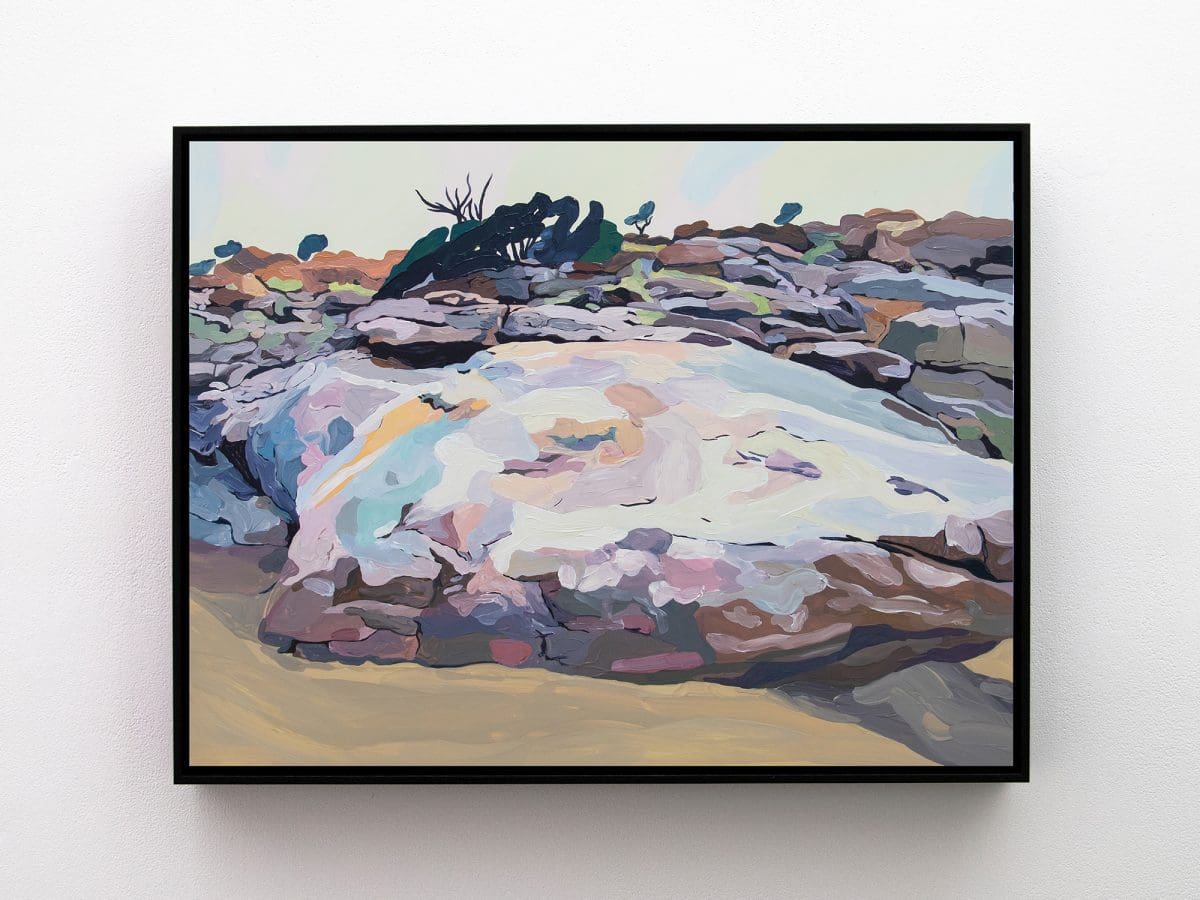

Thea Anamara Perkins is an Arrernte and Kalkadoon artist who creates evocative portraits and landscape paintings exploring being a First Nations person in contemporary Australia. Often drawing from family photographs, Perkins’s work is celebrated for its cinematic yet poignant depictions of family, acts of First Nations resistance, and its strong connection with Perkins’s local Redfern community.

We speak with Perkins in her Carriageworks studio, a site where her grandfather, Uncle Charles (Chicka) Madden, spent over 50 years working on the railroads. Perkins’s mural Stockwoman will grace the walls of Carriageworks for Sydney Festival.

Autumn Royal: You’ve spoken about how portraiture can be a welcoming way of introducing people to uncomfortable themes and truths, as well as representing First Nations people. Can you say more about this?

Thea Anamara Perkins: For me, portraiture is something that started with my family archives and being drawn to certain images and feeling a compulsion to paint them. It was this process that formed my understanding about the complexity of painting these images.

While growing up in Sydney and still having that connection to Central Australia and the painting movement there—which has an incredibly vibrant and powerful history of painting—I would also go to galleries on the east coast and see portraits on walls, and formed an understanding of who gets painted and why they get painted. All these codified elements tell us about the time, place, the artist and the sitters. The paradigms of these times are contained in those portraits. By taking this vernacular, I am using it to express what I want to express.

I was also seeing so much misrepresentation and misinformation about First Nations people in the media and so painting was my way of responding to this and taking charge of representation. I always like to speak from what I know. So, my own family photos and history became a vehicle for expressing what I knew about First Nations people—and the strength and love of our families and communities has meant we’ve survived. I feel a real compulsion to paint these stories. I like the idea that this also ends up speaking to something personal that can also speak to something universal. I love when people say things like, “Oh, I have a photo just like that and of me with my siblings” or “My parents and I went to that place.” Or they can just relate even from the mood or atmosphere in my work.

AR: I think portraiture can have an unassuming way of demonstrating powerful histories and personal ideas—what do you think of this?

TAP: Yes, it’s also a form of leading with love and I think that things can be communicated with a gentle process. And communicating through love is also an ultra-powerful way of communicating an idea or message. I think people are receptive to that.

AR: Your work highlights the significance of First Nations matriarchy and relationships between women. How has exploring your family through your work developed over your practice?

TAP: Something that is very much a part of my work is the fallibility of memory. It’s fascinating because our memories have literally shaped us. They’re so tied to who we are, but they’re also fundamentally unknow-able. You can’t go back to that time, only recounts of that time, especially if you’re a small child. Also, there telling of these stories is totally subjective. Beautiful things happen when details of a story are embellished, or bits are lost—and that’s the same with memory.

By the same token, there’s a through line that draws us back to certain memories and a compulsion to understand. Especially with my portraits, I think it’s been picked up that there’s a cinematic quality to them because they’re from photos on film. If you take this notion of film, then these photos would be stills of the action, and it’s the movement that’s happening around these moments that fascinate me. Photos are in and of themselves very interesting. When I work, I’ll start with a photo and then I take very specific drawings of a scene. Then it’s a free-for-all and things become altered, shifted, saturated, desaturated; all these technical considerations flow into it.

AR: You’re showing a mural work, Stockwoman, as a part of Sydney Festival. Can you talk about this?

TAP: It’s a massive undertaking because I’m scaling up my practice which has been on a smaller and intimate scale. This new work will bring a host of new implications and I’m excited for the challenge.

This mural work is looking at my family history, but this time it’s my great-grandmother Hetty Perkins that I’m considering. Specifically, her life at the Telegraph Station [in Alice Springs], which is where my pop [civil rights activist Charles Perkins] was born. Nana Hetty worked at a place called Arltunga, which is over 114 kilometres from Mparntwe/Alice Springs, and it was where colonisers first built when they came to Central Australia. The work will focus on landscapes, but then it’ll have figures of Nana Hetty earlier in her life when she was about 14 years old, and also of her later on as a stockwoman.

The idea came about after looking at works from artists like Sidney Nolan and Russell Drysdale and thinking about so-called Australia as a concept, and how their works formed the popular imagination—and how it compared to my views as a First Nations person. When I look at the landscape of these places, these views are just a few degrees of separation apart. This got me thinking about figures like Ned Kelly and those who we mythologise. To me, as a First Nations person, it’s people like my great-grandmother, who had to deal with unfathomable and colossal changes in their lifetime, who should be known.

When we think about The Frontier arriving, we often think of it being in Sydney, but it spread over the continent and these women had to contend with the state, the church, all these forces—and they survived with strength and resilience. These women are literally national treasures and there are so many figures that we should all feel proud of and connected with—they should be the heroes of our collective imagination.

Stockwoman

Thea Anamara Perkins

Carriageworks

Until 12 February

This article was originally published in the January/February 2023 print edition of Art Guide Australia.