The wolf is a cipher. It’s a talisman for girlhood fears. The stranger who lurks in the woods. The terror of being devoured by forces that are untameable. But for American artist Kiki Smith, the wolf both creates and destroys.

In Born, a 2002 lithograph, Smith reimagines Little Red Riding Hood. First published in 1697 by French writer Charles Perrault, it follows a girl who leads a wolf to her grandmother—and the wolf eats them both. Born subverts this narrative: the older woman wrenches the girl from the wolf’s bleeding belly. Their arms reach for each other, different versions of the same person. If Little Red Riding Hood asks girls to fear predators, to admit weakness, then Born casts the animal, grandmother and girl as part of a web of interdependence. The grandmother isn’t frail. She isn’t someone else’s appetite. She emerges from the wolf’s body, fully formed.

Born is part of Fairy Tales, a new exhibition at the Gallery of Modern Art, curated by Amanda Slack-Smith, that brings together over 100 works spanning sculpture, installation, painting, photography, animation, augmented reality and costumes.

The fairy tale, of course, has long trafficked in moral instruction. To be told a fairy tale is—especially as a girl—to be taught to internalise a gendered script. I don’t remember the plot of Snow White or Hansel and Gretel or Rapunzel. But I do recall, viscerally, the fictional universe in which a stepmother’s only arc was to jealously covet her stepdaughter’s youth; a realm where witches used gingerbread to trap starving children and the best a woman locked in a tower could hope for was a prince’s rescue.

Born overturns this. The questions it asks— what might it mean for a girl to be born to a wolf? What if savagery and civility were contained in the same body?—aren’t interested in the petty prizes of patriarchy. It imagines a version of femininity that doesn’t depend on masculine power, that envisions itself on its own terms.

Yet, women who reject masculine power have historically been aligned with the monstrous.

“But the feminine is not per se a monstrous sign,” Barbara Creed famously writes in The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis. “Rather, it is constructed as such within a patriarchal discourse which reveals a great deal about male desires and fears but tells us nothing about feminine desire…”

When it comes to women, monstrous could be a synonym for a kind of selfhood based on desires that are mysterious, that can’t be defined or tamed or rewarded.

The fairy tale often imagines feminine monstrosity in the figure of the witch, a source of terror. In Witch House (Séance of the Umbilical Coven), a 2020 installation staged for Fairy Tales by the sculptor Trulee Hall, a black dwelling appears to be carved out of the crooked trunk of a tree. The witch lives alone in the woods without a male protector.

She possesses supernatural powers. She eclipses the need for romance or marriage or sex, rendering her a threat to the social order. Inside Witch House, monitors play stop-motion animations. On screen, performers carry out spells and birthing rituals, drawing viewers into a space in which the gendered rules of the outside world are suspended—if just for a moment.

While fairy tales almost always attribute a woman’s value to her youth and beauty, in the exhibition Ukrainian-born Israeli artist Anna Perach introduces us to the baba yaga, the crone who lives in a hut built on chicken legs. Her wearable sculpture, Baba Yaga, 2019, pays tribute to this fixture of Slavic folklore, who is both terrifying and kind. She gives and takes lives. Across cultures, she is characterised as physically repulsive. The baba yaga’s power revolves less around her palatability and more around her ability to reflect extremes of the human condition.

By exploring the tellings and retellings of the myths we grew up with, and the ways in which artists reinterpret these, Fairy Tales shows how stories morph to reflect the culture. The witch and the crone, monstrous as they are, today offer versions of womanhood that are expansive rather than prescriptive: these characters have agency. They don’t quash their knowledge, aren’t forced to be “good” or “nice”, aren’t bullied into the notion that their power stems from being young and desirable.

“In the best-known fairy tales, the woods are a foil to the home, a place where little girls shouldn’t be, a space in which you swap goodness to become monstrous.”

They are antidotes to a moment in which gendered scripts are encouraging women to shrink once again, to describe the substance of their lives via TikTok phrases like “girl dinners” and “girl failures”.

Or the “tradwife” label (evoking a kind of prelapsarian femininity made famous by fairy tales), which advocates for women to give up work, tending the home for their prince—this has emerged as the questionably empowering answer to the impossible puzzle of ‘having it all’.

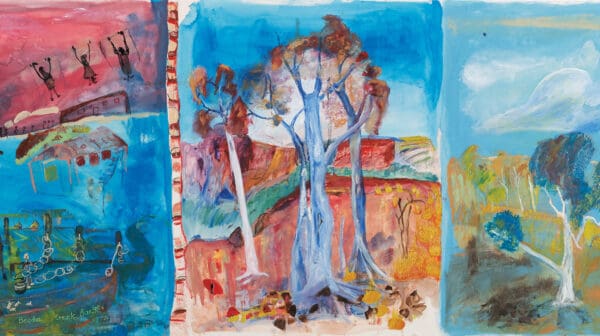

In the best-known fairy tales, the woods are a foil to the home, a place where little girls shouldn’t be, a space in which you swap goodness to become monstrous. Fairy Tales features an image from Tracey Moffatt’s 2000 series Invocations, where a girl wanders alone, surrounded by sentient trees. Your imagination fills in the blanks: around the corner there could be a wolf or danger—she’s facing the potential consequences of her freedom, for veering off the path society has set for her.

But she’s not the typical princess. She’s a young Indigenous girl lost in the European woods and the trees look surprised. If the woods represent a space where values can shift, the lost girl creates new language for an old story.

Just as Moffatt remakes the fairy tale as a site of transformation, metamorphosis defines Smith’s Born, where the wolf is less predator and more mother, a kindred spirit. The woman, the girl and the animal are intertwined, inhabiting the same realm, imagining new possibilities for each other—and for the power of the fairy tale itself.

Fairy Tales

Gallery of Modern Art (Brisbane QLD)

2 December—28 April 2024

This article was originally published in the November/December 2023 print edition of Art Guide Australia.