Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

The National Gallery of Victoria – The Ian Potter Centre (NGV Australia) has reopened and there is still time to catch the massive retrospective show DESTINY, which features more than 100 artworks by Destiny Deacon.

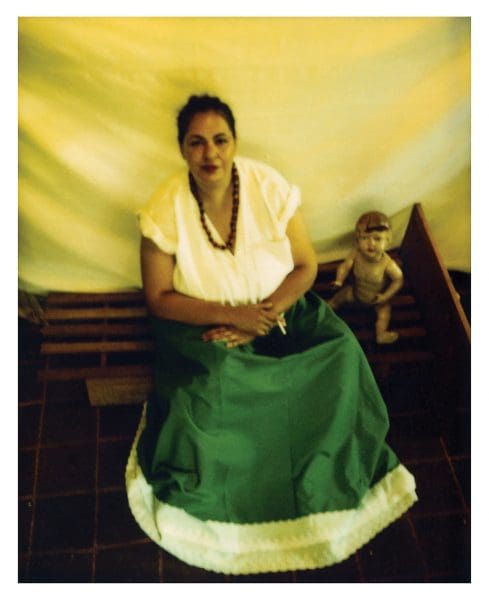

Destiny Deacon was once recorded as saying of her art that there is “a laugh and tear in each picture”. DESTINY, the survey of her work, under the curatorial eye of the National Gallery of Victoria’s Myles Russell-Cook, intensifies that idea: passing from one Deacon video or photographic installation to another, we might easily waver between wistfulness, amusement and a sense of sweet affection.

As Russell-Cook says, one of the things he loves most about Deacon’s work is that you can stand in front of it for ages, in the white cube that is a gallery, before you remember how wonderful it is that art can be funny. And before we’ve stopped laughing, we recognise this is the sort of humour where an observer might not be sure they are actually “allowed” to laugh. Take, for example, Smile, 2017—a deceptively simple work that shows the iconic smiley face, but one constructed with two black dolly heads for the eyes and a boomerang for a mouth.

“In blurring the line between the sad and the humorous, she shows audiences how the truth is often absurd,” says Russell-Cook.

Deacon has been on the scene for about 30 years, and she has become a much-admired figure, especially around the Melbourne visual arts world, partly because of this delicate ability to infuse a great sense of mirth into deeply troubling, serious subject matter. Where other artists might be hesitant to forage, even those with Indigenous heritage, Deacon goes boldly, and with great warmth.

Born in Maryborough, Queensland, Deacon came to Melbourne when she was aged about two.

While she has not grown up on her families’ Country, she has certainly embedded herself in Melbourne, which is inscribed strongly throughout her work through images such as a creepy Luna Park face, a scene from the top of Eureka Tower, dallying with the Moomba king and queen, and other recognisably local scenes.

A slight departure from this is one of the last works in the show’s trajectory, titled Postcards from mummy. Two years after Deacon’s mother died in 2006, the artist made a journey that replicated one her mother had made as a very young woman from Cooktown to Brisbane. As she travelled, Deacon mailed postcards to herself back home in Melbourne. “While it might be easy to read this work simply as a tribute to her mother, it is more about reflecting on and coming to terms with the start of her mother’s adult life,” says Russell-Cook. “But it also speaks to a universal experience of Indigenous people around dislocation, and being a stranger in ancestral Country – but feeling the need to reconnect. That is fascinating in the context of how we identify Destiny so much as a ‘Melbourne artist’.”

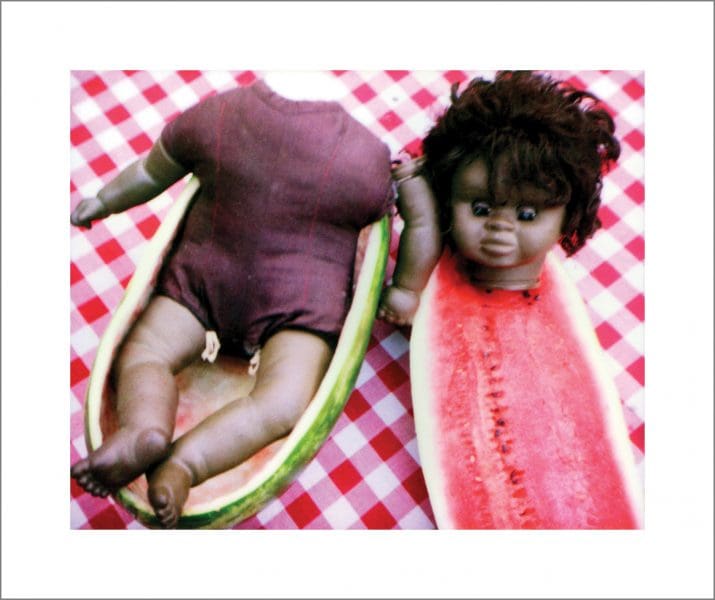

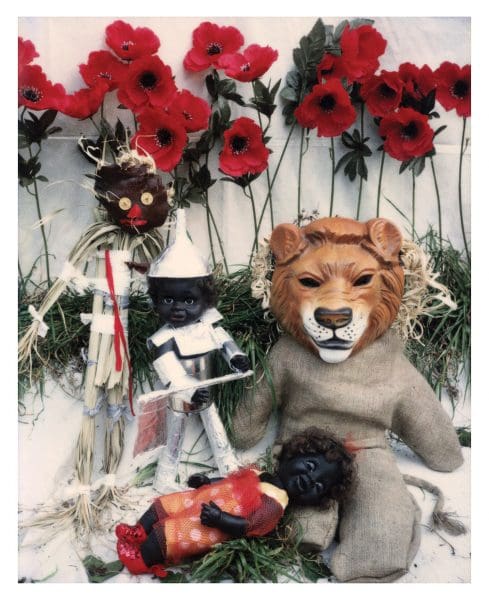

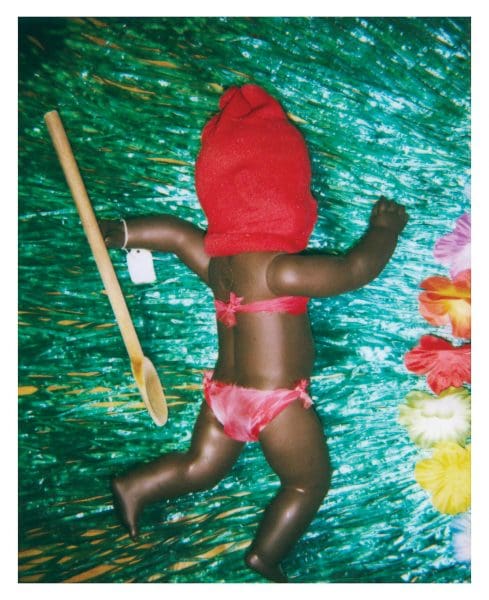

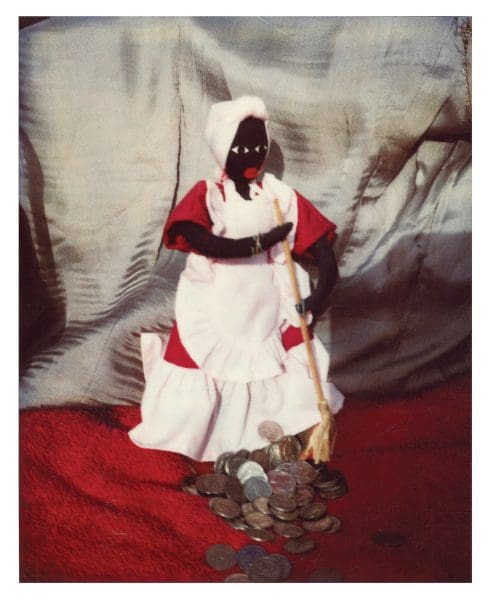

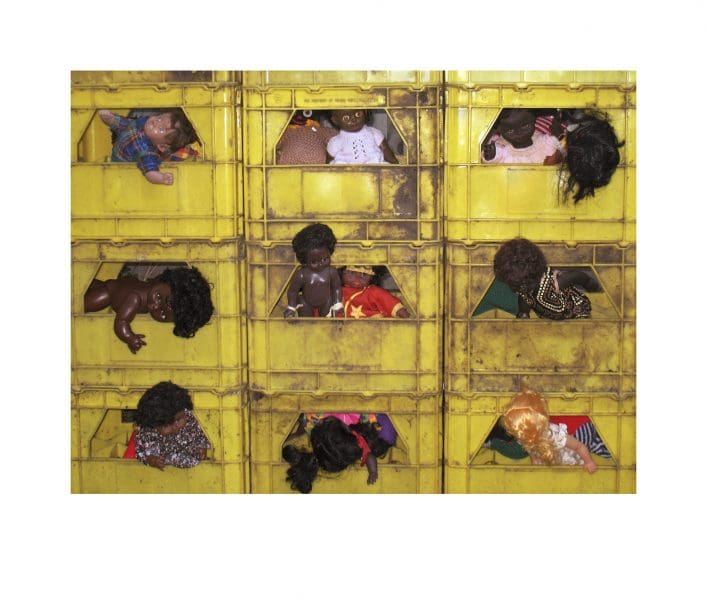

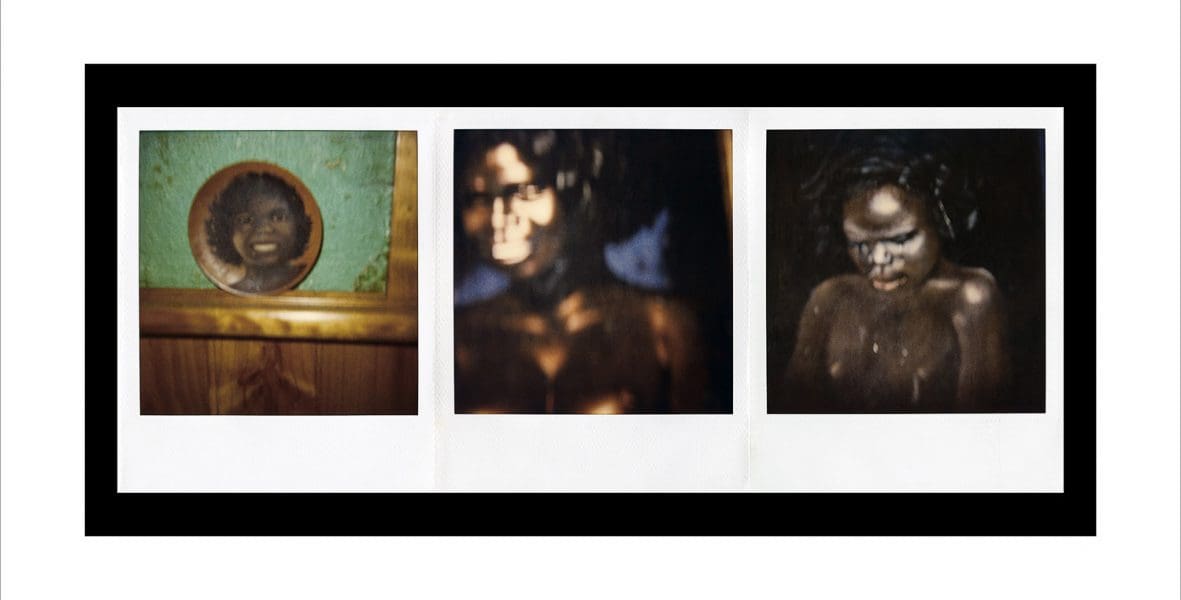

While Deacon eschews ‘artspeak’ and prefers to let her work speak for itself, she is at the same time remarkably nimble with the variety of ways her works manifest. One example is an installation work by Deacon (and her long-time collaborator Virginia Fraser) called Colour Blinded. Appearing just after the halfway mark through the exhibition, this multi-work arrangement is inside a curtained-off room and features six black-and-white photographs taken on orthochromatic film—a type of film that produces unexpected effects by excluding the colour red. The photos feature one of Deacon’s mainstay images: black dollies collected in charity shops or through friends. They are portrayed in various social situations but are accompanied by two Perspex cubes (titled Snow storm) in which golliwogs are imprisoned in a dense filling of Styrofoam balls.

As Russell-Cook observes, these cubes invert the idea of the “white cube” gallery—especially as the room’s lighting is done with low-pressure yellow-tinted sodium freeway lamps. “This is a dig at the whole idea of Indigenous art being presented in the white cube/art gallery,” he says. “But it feels like the white cube has been contaminated because of the lighting.” In this way, the audience’s skin takes on a similar saturated hue as the walls and the photographs. “We are literally ‘colour blinded’.”

This room also features two video works in which viewers are directly addressed and made to feel like intruders interrupting a private performance. Russell-Cook interprets these as entangling us as active participants in the work—and, by default, in the whole story of Indigenous suffering that flows beneath the surface of the entire exhibition.

All this contrasts strongly with another installation in the show—a life-size lounge room, complete with couches and a large swathe of Deacon’s personal collection of Aboriginal kitsch paraphernalia, much of it produced in the first three quarters of last century. This, along with many other works in the exhibition, transports us to the “uncanny valley”, which Russell-Cook explains relates to the degree of an object’s resemblance to a human being and the emotional response to such an object. But these objects are not presented with derision or rejection: Deacon, he says, simply wishes to “rescue” them.

“She is not passing judgement on the objects,” he says. “She just doesn’t want to see them in some white home, and that’s why she began collecting them. As you look at them, you start to see the characters you have met throughout the show appearing and elevated to this new role within the gallery.”

DESTINY

National Gallery of Victoria – Australia

23 November – 14 February 2021

This article was originally published in the March/April 2020 print edition of Art Guide Australia.