The ‘Two Cathies’ found each other over a decade ago. In 2009, artists Catherine Bell and Cathy Staughton painted each other’s portraits. When Bell met Staughton, she knew it was the beginning of an ongoing collaboration and friendship. Both artists have a practice spanning over 30 years and while their work may seem disparate on the surface, there is connection in the introspective ways these women capture the world around them, from technology to emotion to grief.

Bell met Staughton through Arts Project Australia (APA), a studio and gallery for artists with an intellectual disability, where Staughton has practised for over 30 years. Primarily a figurative painter, Staughton creates vivid scenes capturing everyday people, icons, angels, robots, and cats. She’s painted David Bowie and Yayoi Kusuma, two iPhones kissing, the rides of Luna Park and matrilineal scenes, like a woman breastfeeding. Last year, Staughton was a finalist in the Rick Amor Self Portrait Prize with her painting, Queen Cathy Staughton.

Meanwhile Bell’s practice encompasses performance, video, installation, vessels and participatory artworks, with a particular focus on grief, death and ritual. In the 1980s, Bell worked at an aged care facility and volunteered at the Queensland AIDS Council. She saw the death of elderly women alongside the death of young men almost daily. Ever since, compassion, and a sense of understanding sadness and devastation, has filtered into Bell’s art.

For her 2017 exhibition We Die As We Live, Bell facilitated workshops with palliative care staff through a yearlong socially-engaged project, where creative responses were gathered to look at experiences of death, as well as meaning, in life. The public viewed these responses, and as one person said, “I have often thought of death as a lonely, isolated experience but this exhibition shifted my thinking on this: it helped me see the interconnectedness even in the final stages of life.”

The spectre of death is clear in Bell and Staughton’s 2020 collaboration, The Artist and the Mermaid. The silent film was dedicated to Staughton’s mother, who died the year before. It features Staughton finding Bell as a mermaid—or in the words of Staughton, a “lovely lady fish”. Staughton frees Bell’s mermaid tail from fishing net, nurses her back to health, paints her portrait, and releases her back to nature. It’s an inversion of ‘sensual mermaid’ narrative. It’s a feminist, care-centred retelling that addresses the representation of women and people with a disability, making unseen relationships visual through parable.

As Bell says, “Our collaborations reveal our mutual vulnerability… It was liberating capturing our unscripted interactions on film and the surprises that emerge from improvisational performance, Cathy’s theatricality, and a slapstick sense of humour documented on camera and canvas.”

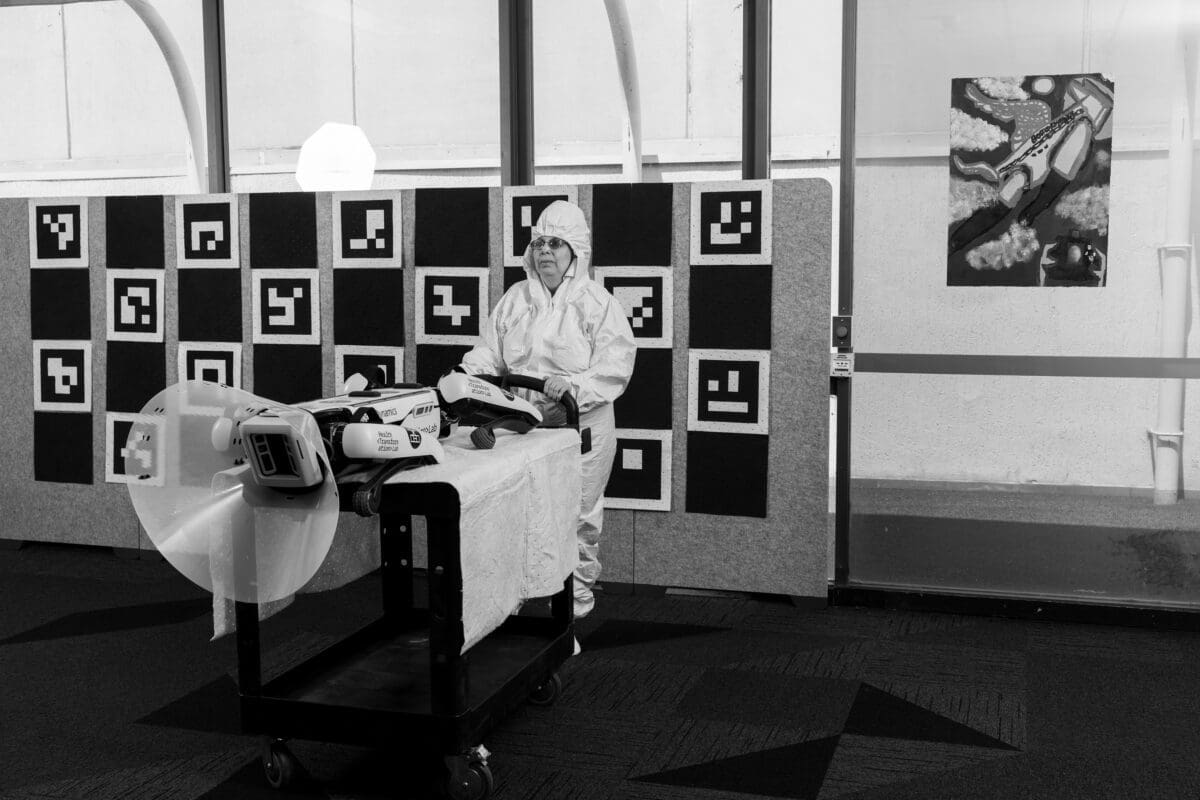

Now, Bell and Staughton’s collaborative relationship is turning technological with Dog Robot Space Star at Gertrude Glasshouse. Recently, researchers at RMIT Health Transformation Lab invited Bell to partner on a project—and when discovering it involved their robot ‘Spot’, Bell immediately thought to collaborate with Staughton, an avid lover and collector of all things robotic.

Spot is an agile robot that navigates terrain with unprecedented mobility, allowing users to automate routine inspection tasks and capture data, accurately and frequently. Its original application is in warfare, policing and construction. The potential uses, such as detecting intruders or signalling if an aged care resident has fallen, lends Spot to innumerable possibilities—and yet it’s the Two Cathies who are looking at the aesthetic and ethical implications.

During a six-month residency at RMIT working with Spot, Staughton painted her interactions with the “Dog Robot” and Bell created the video work, Dog Robot Space Star. The storyline is unique. Inspired by Archie, Bell’s dog who is terminally ill with bladder cancer, the film sees a static felt dog suddenly transform into Spot—yet Spot is unwell and is cared for by Staughton.

The film also includes Staughton’s paintings of Spot, which are cast amongst an office backdrop that is reminiscent of when the domestic and professional spaces merged during Covid lockdowns.

“The film has a futuristic, sci-fi vibe because it is where the robot manifests, at a dystopian moment in time when civilisation hovers on the threat of pandemic extinction,” explains Bell. “It made me think of movies set on spaceships, and how claustrophobic they are despite the amenities and creature comforts, including robot companions.”

By looking at robots as companions, Staughton and Bell create an important relationship between humans and technology. As Bell says, “In the film, the robot’s death is foreshadowed by incontinence and sporadic power outages that Cathy dutifully attends. Cathy is quick to covet the latest model iPhone or computer, but when it comes to robots her devotion and care of her collection is endearing.”

What infuses the film, and Bell and Staughton’s collaboration, is care and ethics. It is not usual for a neurotypical and neurodivergent artist to collaborate so fruitfully, for so long. As Bell has written, the pair’s “collaborative model provides a valuable conceptual framework to think about neurodiverse interactions and how care ethics can reorientate practices, values and procedural standards in professional studios that support artists with disabilities”. It is about creating art in ways that are inclusive, ethical, and genuinely relational.

Dog Robot Space Star

Catherine Bell in collaboration with Cathy Staughton

Gertrude Glasshouse

20 April—20 May