Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

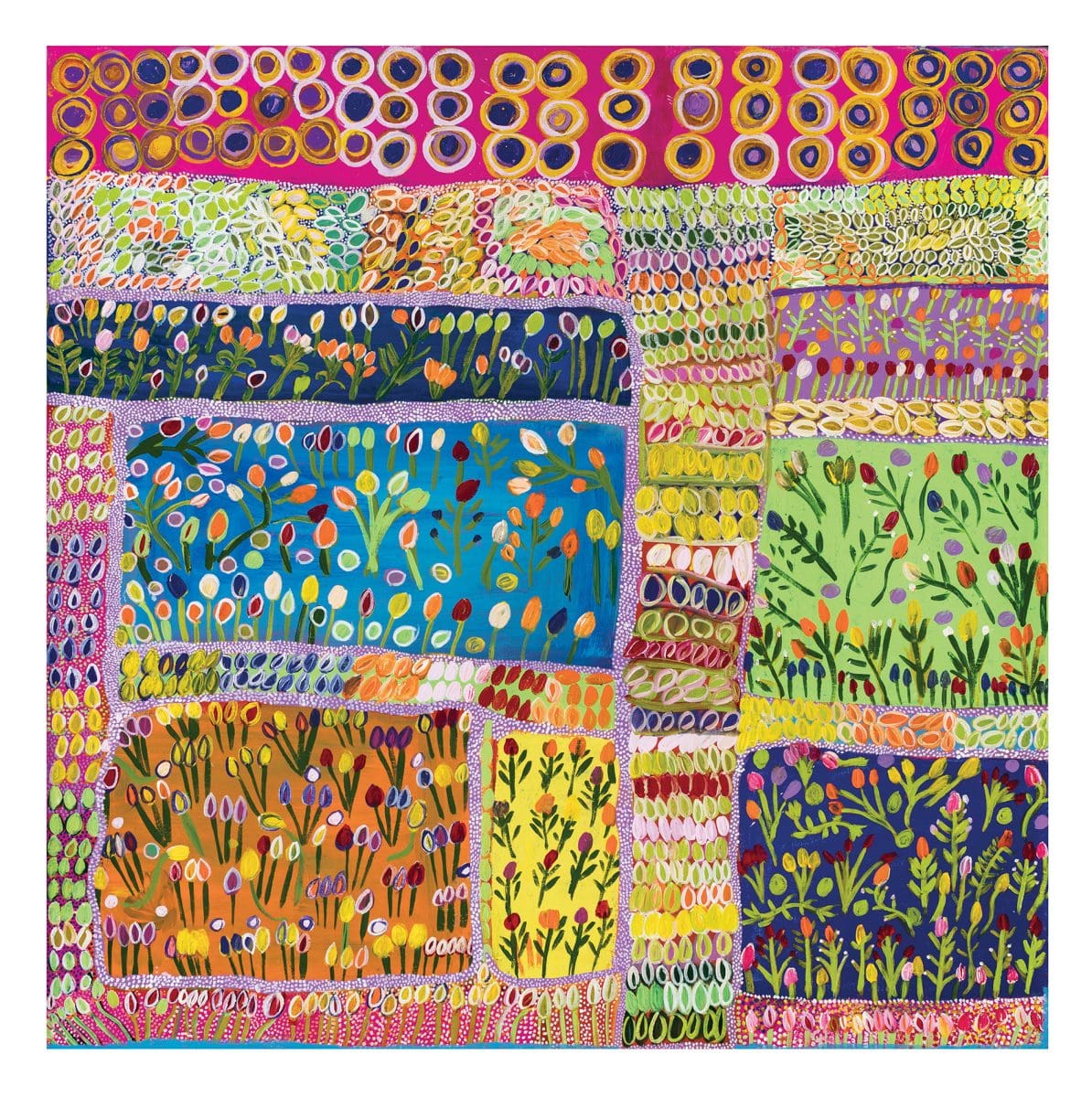

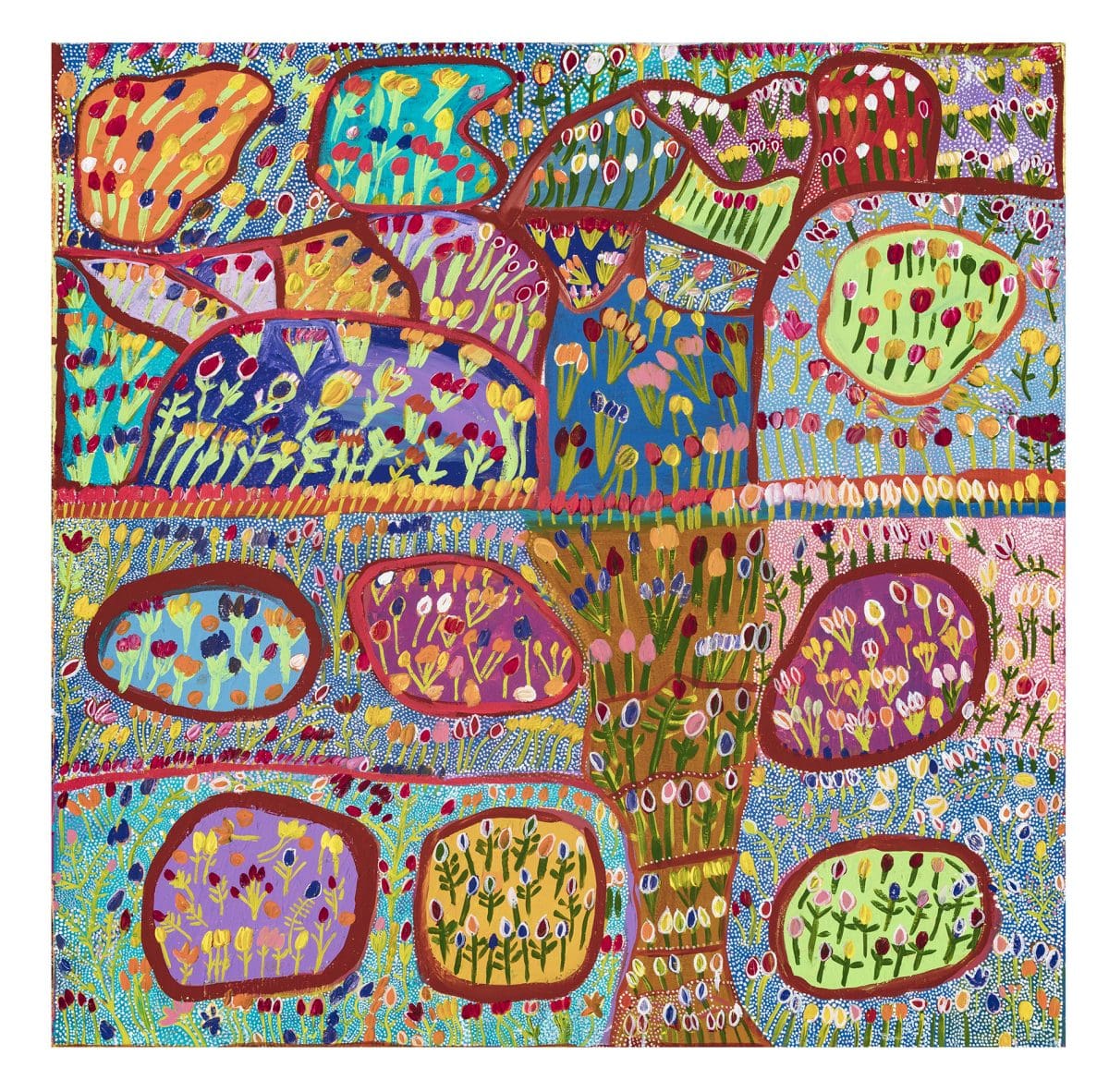

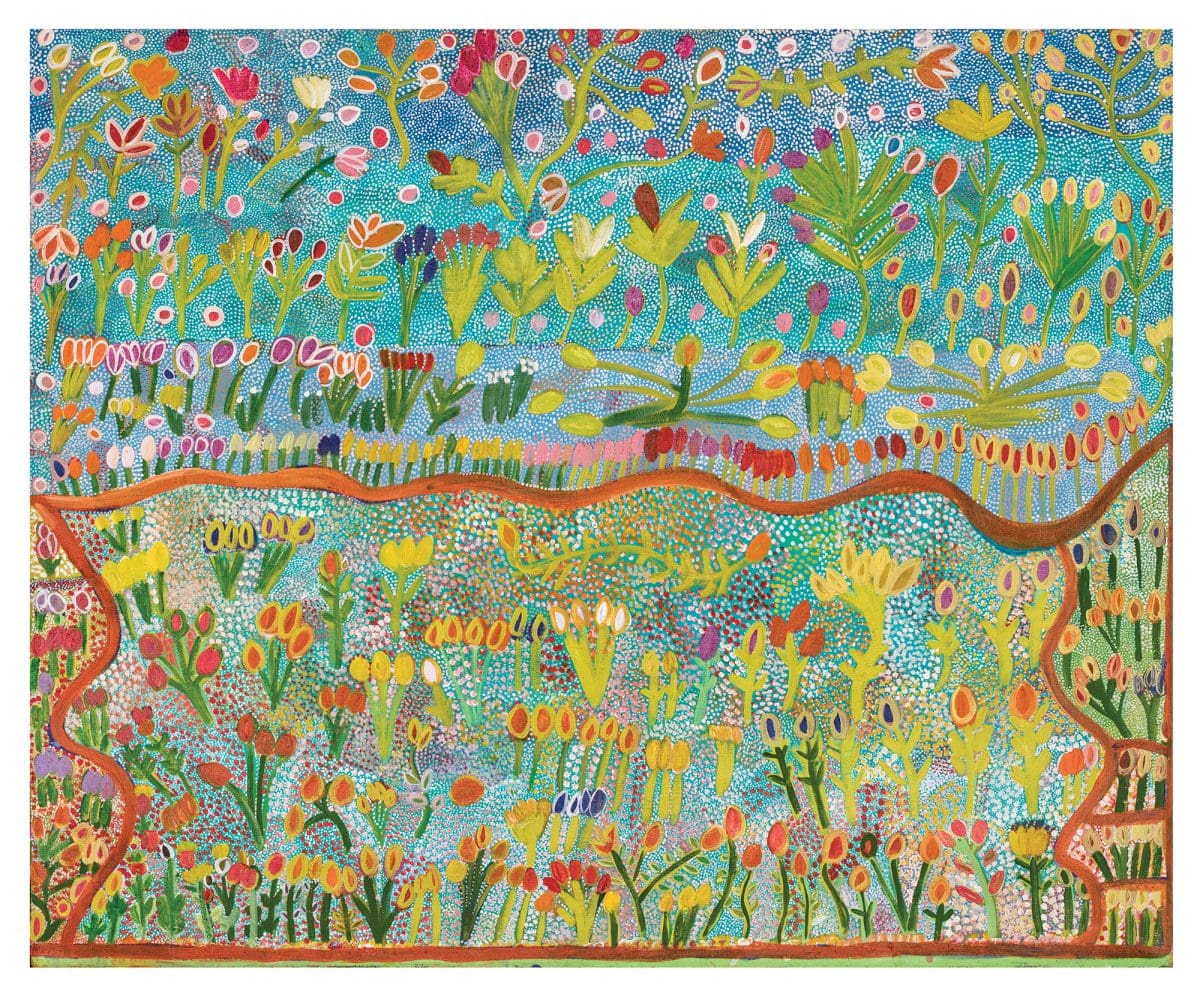

The searing colour palette in Gwenneth Blitner’s landscape paintings capture her Country in technicolour joy. Born and living in Ngukurr, a remote Aboriginal community on the banks of Roper River in southern Arnhem Land—formerly known as Roper River Mission—the 62-year-old paints from a place of happiness because, as she says, it “feels right”.

Such an impulse is wildly evident in the images she creates, where the delicate grouping of flowers— a reoccurring motif in her work—bursts with blissful energy. Blitner thinks about Country while painting, replicating her Marra, Nunggubuyu environment with a dazzling beauty that reveals multiple layers of landscape; red deserts, rocky escarpments, gorges, rivers and waterfalls. Yet Blitner also breaks through the standardised conception of Arnhem Land, bringing wildflowers and billabongs to the forefront. In paintings that overflow with colour, Blitner offers new ways of thinking about remote desert areas. Her memories of Country are full of bush flowers reminding her, as she tells me, “how important land is”.

Despite Blitner’s distinguishing energy and unique form, little has been written about her art. Stylistically her paintings reflect a growing body of Aboriginal art that defies categorisation like ‘remote’ or ‘traditional’ against ‘new’ and ‘contemporary’. One recent example of this is Yolŋu artist Dhambit Munuŋgurr’s Bees at Gäṉgän, which won the 2021 Telstra Bark Painting Award. The judges described the predominantly blue bark painting as a blurring of distinctions between traditional and contemporary Aboriginal art—and the same could be said for Blitner.

Blitner’s art complicates the idea that all Aboriginal art from remote areas is ‘traditional’ or even ‘authentic’—an idea rampant in the colonial history of curation. These restrictive frameworks often separate contemporary urban Black art from traditional regions, which in turn limits our ability to understand the connections between all practicing First Nations artists across the continent.

In this way, Blitner’s art is contemporary in its aesthetic form, messages and experimentation, while also grounded in the remote geography she inhabits. Her work has evolved over time, beginning with abstract and less figurative painting. “I didn’t study art but learnt from Aunties just by watching,” she says, which is demonstrated in her boundless free forms which feel instinctual. Both her father and grandfather were also influential in teaching her many foundational techniques, but she quickly developed her own style. “My paintings got better and better over time.”

Such a development is evident in the confident collection she has produced, ranging from understated reduction lino prints of animals such as Jambarrina (bush turkey) to the lavishly intricate canvases such as Marra Country and Ngukurr Cemetery. These later pieces, featured in Tarnathi 2021, are where diverse floral ecologies and billabongs burst in vivid colours and patterned details.

When writing about Aboriginal art for the recent National Gallery of Victoria Australia exhibition TIWI, which showed a collection of work from Tiwi artists, curator Tristen Harwood illuminates that “the wonderful artworks in TIWI are unable to be contained; they come into perpetual being, exceeding the very impetus of framing—a resounding, runaway glimmer that can be discerned, but not defined.” Blitner’s work is also impossible to contain. Its evocative imagery, particularly evident in her bush flower landscapes, elicits wide ranging emotions and impulses that speak to her love of Country, as well as wider feelings of excitement and passion. These same paintings also refuse colonial framing by arts institutions because they speak to pleasure, happiness and a rejection of the overused imagery of Country. They are not what white institutions or audiences may expect, as traditional landscape motifs are absent in much of her work.

On this level Blitner’s art shares commonalities with contemporary urban Black artists. Both successfully evade and critique historical assumptions about past and present art, or ‘new versus old’ within Aboriginal culture. Her art also goes beyond a merely anthropological gaze of Aboriginal art. This is most obvious in the way Blitner describes her practice, community and lifestyle—an overlapping where multiple interests intersect. As she explains, “I love to go fishing and hunting and paint the landscape that I love.” While Blitner’s cultural lineage may not have been severed in ways some urban Black communities experience, her painting is about herself and her own desires: “If I couldn’t paint, I would get bored. It makes me happy.”

The exceeding happiness derived from painting, and Blitner’s drive to keep pushing her practice, broadens the view of remote or traditional Aboriginal art. When I asked Blitner what it felt like to have her work exhibited and celebrated in major cities and festivals throughout the nation, she answered that “it is important to tell stories about her Country.” This legacy is powerful but so is her contemporaneous style—where colours and floral patterns explode in unexpected ways. These paintings of joy, of “feeling right”, highlights to audiences that colonialism has not broken Aboriginal peoples’ ability to define sovereignty on our own terms.

Tarnanthi 2021

Art Gallery of South Australia

15 October—30 January 2022

This article was originally published in the November/December 2021 print edition of Art Guide Australia.