Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

I was in my first year of high school, in the midst of a dry Western art history class, when I first heard that ‘men dominated the art world’. I distinctly remember scoffing. Until then, my experience of art had centred on primary school classrooms and my mum’s marvellous craft box. Perhaps it was the ruffled art-room smocks, or the constant, inexplicable surplus of pompoms, or that my art teachers and most eager peers were girls and women; but to a twelve-year-old, artmaking seemed markedly female.

I soon learned that the practice of art does not have an equal relationship with opportunity, recognition or employment; that the art world—that ecosystem of artists, collectors, galleries, journalists and audiences—had also been scoffing, for centuries, at girls and women who aspired to make things that could speak as part of a shared culture.

Gender disparity in the arts sector is complex: past imbalances have dictated an inaccurately male-centric art history narrative, which exerts a powerful influence over the practices and policies that determine which artists receive opportunity and representation. There’s a lot of work to do, and the people rolling their sleeves up in the Australian art landscape are focused on both systemic change and the desire to nurture resilient, supportive communities.

In May 2019, The National Gallery of Australia (NGA) announced ‘Know My Name’: a multidisciplinary push towards gender equality. Its hashtag #knowmyname asks the public and art industry to build awareness of contemporary and historical female artists. This message is scaffolded by a flurry of new programs: six months of all-female exhibitors in 2020, a major commission from Patricia Piccinini, a focus on Angelica Mesiti and new guidelines for organisational gender equality in collaboration with The Countess Report, a project examining equality in the Australian contemporary art sector.

The NGA’s tenacity was sparked by a statistic: only 25 percent of NGA artworks are made by women. As the collection (some 166,000 items) signifies Australian identity and history at a national level, this finding was “glaringly problematic,” says Sally Smart, artist and NGA Board Member. “Practically speaking, the campaign encompasses exhibitions, commissions, acquisitions and partnerships with some of Australia’s leading female-identifying artists. But critically, it’s intergenerational and it’s ongoing. This is not one season of women-themed programs: it’s embedded across the whole institution,” says Smart. As a federal gallery, changes at the NGA indicate how hungry Australia is to take women leaders and practitioners seriously.

The NGA’s broad approach is necessitated by the subtlety of the task at hand: “It takes a lot to remember an artist’s name,” Smart explains. “It’s not as simple as connecting with an artwork in the gallery. If that work is not talked about, taught, written about, reproduced or studied, then it’s not reinforced. The name slips away.”

Meanwhile, the same few blockbuster-level male artists are well remembered. “Audiences see what the institution has provided them to see, mostly without question,” says Smart. The human animal craves the familiar: identifying and reiterating popular images and stories. It’s a mundane tendency, but in recognising it, the importance of spotlighting female voices on major platforms becomes clear.

The narrative of Australian art history is built from the fabric of the national collection pool: the sum total of artworks held in public institutions, private collections and NGO holdings. “A curator is not able to tell a story, whether conceptual, political or personal, if the artwork to tell it is not acquired,” confirms Smart. For an artwork to enter the popular imagination — via an exhibition, publication, lecture, article, essay, report, postcard or television special — it must be present and accessible in the collection pool: “It’s about women artists being in the culture.”

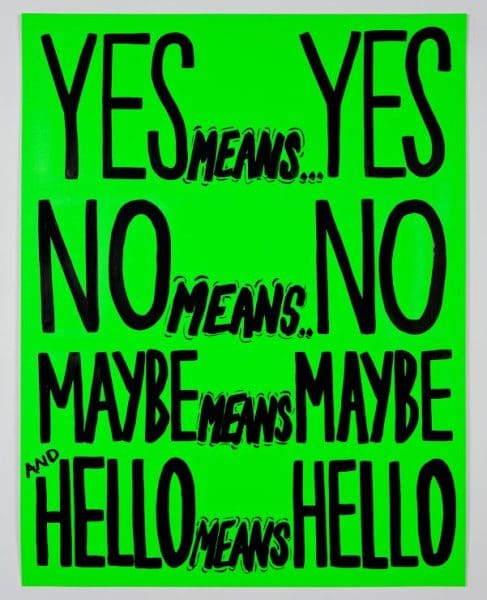

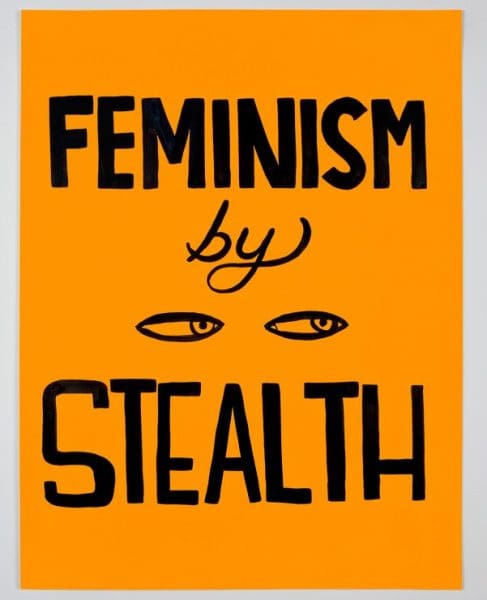

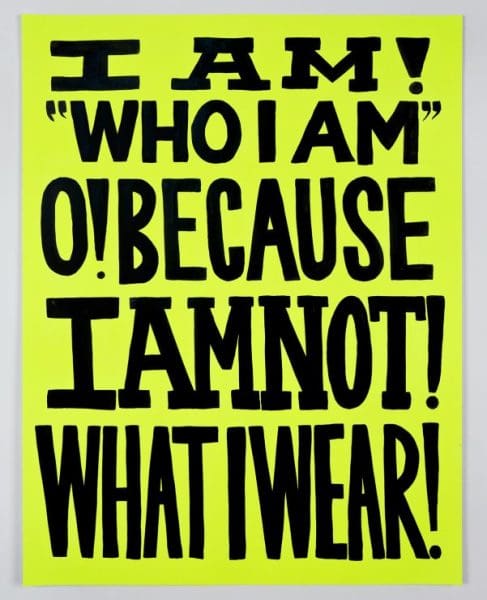

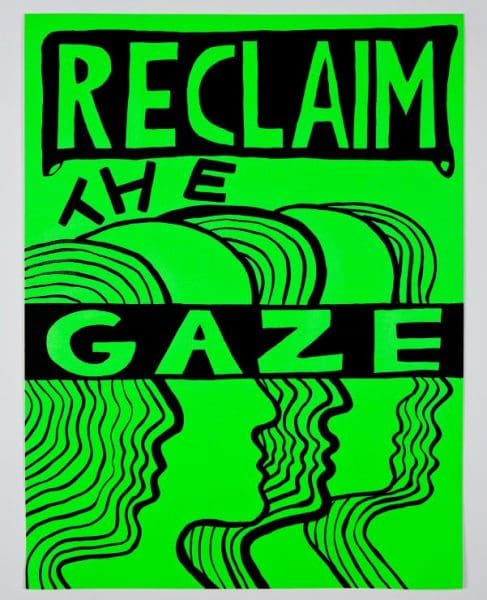

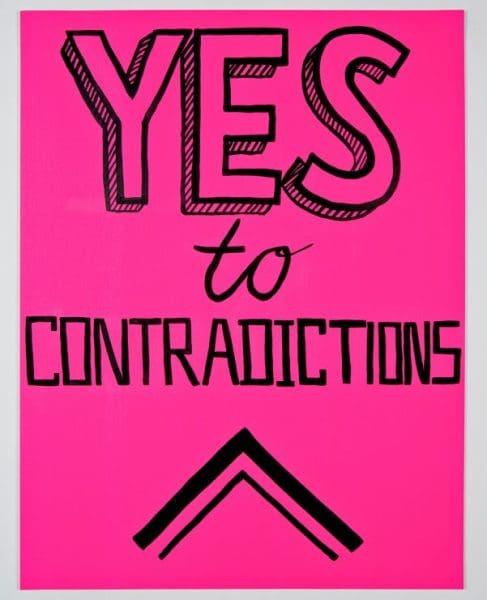

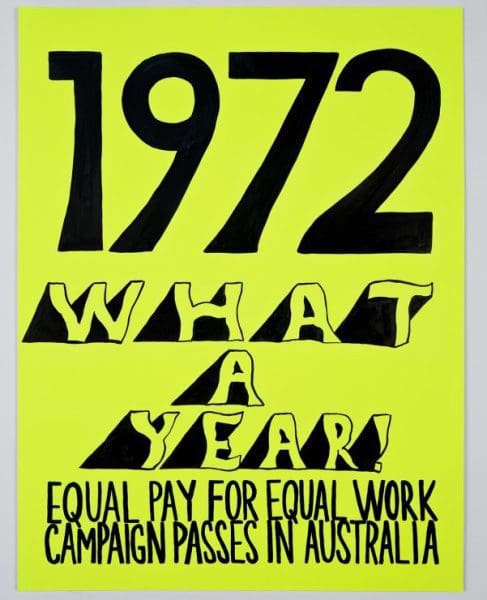

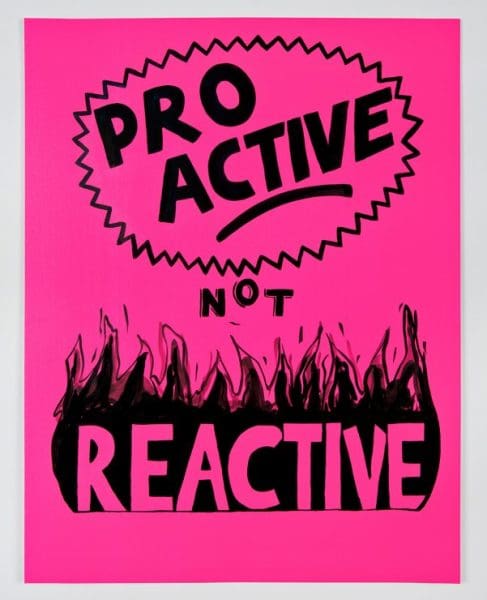

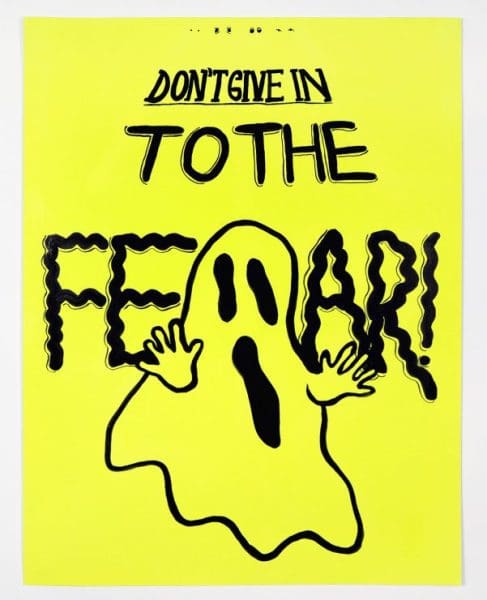

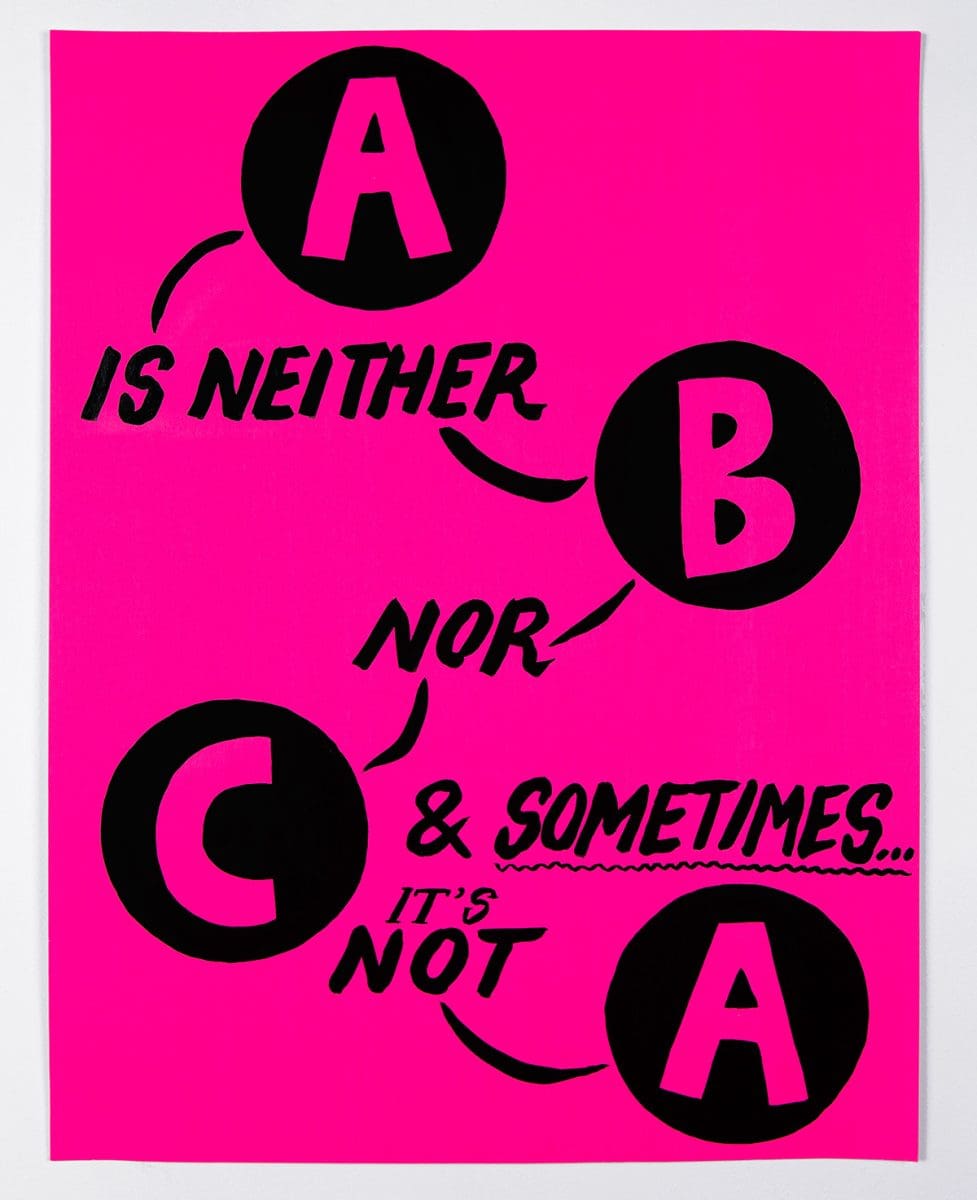

“The back-end research to historicise women artists who’ve been left out of the canon is really important,” emphasises Gemma Weston, former curator of the Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art. Comprising over 700 works, the Cruthers is Australia’s largest standalone collection of art made by women. In 2015, it acquired Things Learnt About Feminisim #1 – #95, a series of lively fluorescent posters by Kelly Doley, which were subsequently loaned for the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art’s 2017 survey on feminism Unfinished Business where, says Weston, “they became a really prominent part of the conversation”.

In 2018, Weston used the Cruthers as a podium to mount No Second Thoughts, a revisiting of the ARTEMIS Women’s Art Forum, a 300-strong collective of WA artists. Former members attended the opening and many have initiated new projects together. “It was a formative project for me,” she reflects. “The ARTEMIS archive tells a rich, detailed story about contemporary art and feminist activity in Perth in the 1980s. All that information had been under my nose, masked by an inconsistent local art narrative. It was a matter of refocusing.”

Amending historical collections is a slow, knotty task. Initiatives like Into the Light unearth women artists who have been discounted from art history, through primary research: trawling auctions, deceased estates, archives, enrolment data and local publications. Funded by the Sheila Foundation and spearheaded by historian Dr Juliette Peers, Into the Light has already recovered evidence of over 431 women artists working before 1960 – in New South Wales alone – only 10 percent of whom already appeared in the public record.

“As a culture, we need to form a more realistic picture of who is making art. When we repeat the same few names over and over, the complexity of the whole picture diminishes,” says Weston. All this begs the question: how is artistic significance recognised, and are those criteria stacked in favour of male artists?

In the past, forces barring women from significance were sociallyingrained: “Going back to Linda Nochlin’s [1971 essay] ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists’, the criteria for significance are based on gendered concepts of value and structures that preclude women from practicing professionally,” explains Weston. Inadequate access to childcare, pressure to commit to domestic labour, stigma around public breastfeeding and the exclusion of women from life drawing classes: “These structures impacted on women’s ability to work professionally, thereby reinforcing the notion that their work wasn’t ‘professional’,”

Today, other setbacks are in play: female artists who disappear from the public eye for five years to raise children can lose their perceived standing; those who adapt their practice for a home studio are sometimes disparaged for their pursuit of ‘less serious’, non-industrial or smaller-scale media; changing your surname can muddy your professional profile; feeding and putting down a baby exerts time pressure.

“The tremendously imbalanced system became clear to me when I was working as a consultant,” says Lisa Fehily, founder of recently launched Finkelstein Gallery. “When well-known male artists exhibited, collectors would favour the largest and most expensive pieces. That those artworks proliferate in big collections gives the false impression that men are more likely than women to make large, expensive artwork. It’s a stereotype that hinders both genders.”

Finkelstein Gallery represents two international and nine Australian artists. One is Lisa Roet, whose contribution to international discussion on humanity and inter-species relationships is substantial. “Lisa studied linguistics, worked with gorillas and collaborated internationally. She’s currently in Paris developing an extraordinary forthcoming project with Jane Goodall and UNESCO. Our job is to show the breadth of her practice and find a place for her work in significant collections.” The Finkelstein stable is all female. For Fehily, it’s about leading by example to create an artworld in which female voices are not a special interest category. “We represent strong women,” she beams.

But marketing ‘all-female’ can be tricky. “When things get badged as ‘women’s art’, there’s an assumption with audiences that they’re relevant specifically to ‘women’s interests’,” explains Weston.

“Over six years of Cruthers’ public programs I was fascinated to see an audience that was consistently almost entirely female, as though male patrons thought the subject didn’t apply to them.” This phenomenon is complicated by the resurgence of craft. “That the whole art community is exploring ceramics, jewellery and weaving again is wonderful,” says Fehily, “but in the past we’ve described men working in this way as career artists and women as hobbyists or crafters. We must be careful to give each artist the gravitas their work deserves.”

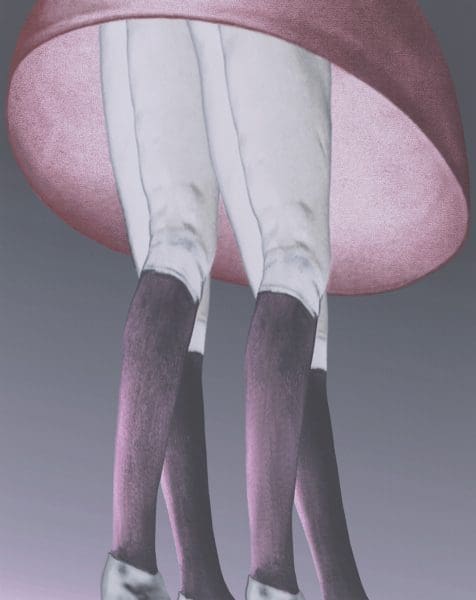

Harkening to women’s artistic self-expression is one way forward. The touring exhibition In Her Words presents 27 women who wield the camera to assert their vision through photography. Inspired by Jill Soloway’s discussion of the female gaze, curator Olivia Poloni was interested in “the idea that women narrate with empathy and aren’t always trying to pleasing the eye.”

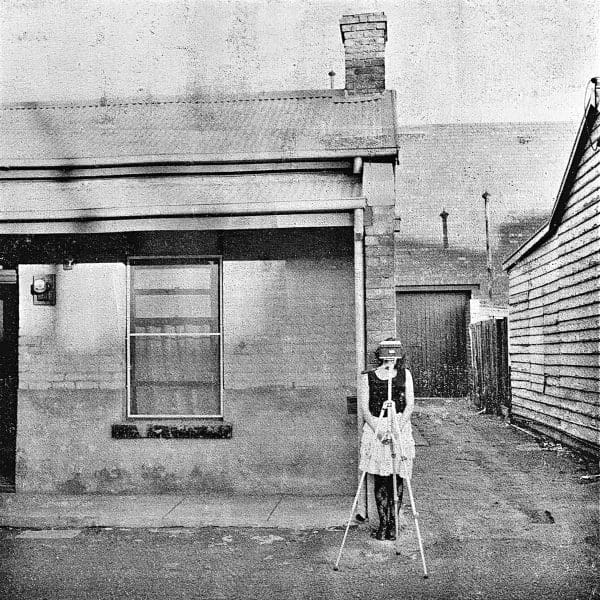

In Her Words was kindled by Poloni’s experiences of female camaraderie: “I have been fortunate to receive true mentorship from senior female artists like Polixeni Papapetrou. It’s difficult to walk into a big gallery and see a majority of male voices when you know how much can be learned from our leading women artists.” Papapetrou’s I Am Camera, 2018, provides a powerful account of creative sovereignty: “It was her last work, the only work she put herself in. She stands behind the camera, in full control and with full dedication to her work.”

One disappointment for Poloni was finding that her ability to give wall space to a diversity of female-identifying artists depended heavily on the collection pool. “Queer and non-binary artists are severely underrepresented. That was really difficult. ‘Female’ is a huge category and I’m determined to find room for everybody in my future projects.”

Intersectional representation is also a core objective for Miranda Hine, curator of the exhibition New Woman, currently showing at the Museum of Brisbane: “Women and gender-diverse artists are creating some of the most innovative artwork in Brisbane right now, so working with them was obvious, rather than quota-driven.” New Woman recounts a 100-year history of female artists, including the energetic and generous Vida Lahey and Daphne Mayo: “They singlehandedly changed the face of art and art education in Queensland, but are no longer remembered by the public they served.”

Tracing the history of female Indigenous artists prior to the richness of Tracey Moffatt and the 1980s also proved difficult: “Artworks were being created, but they were not valued enough by the Western institutional ‘eye’ to be collected,” laments Hine. Aboriginal communities in which art was practised communally or where techniques passed between generations also received less recognition from an art world that bought into the trope of the “artist as individual. These gaps talk about Brisbane’s social history as much as its art history,” says Hine.

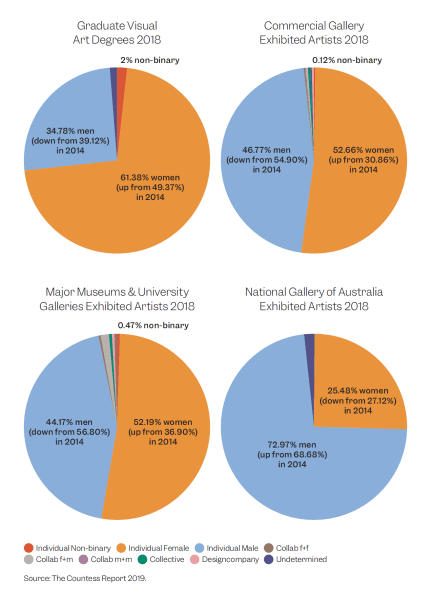

The privilege, principals and cultural baggage of those who decide what enters the collection pool is a keystone of the gender conversation. Women do not comprise half of upper-level staff in many Australian arts organisations. Recently, the Countess Report published its 2019 census on gender equality in the arts. Progress at commercial and independent galleries was celebrated across the industry, but one number stuck out like a star picket from a birthday cake: only 12 percent of state gallery directors and CEOs are women.

Of course, the collection pool is not solely constructed by large institutions. Private collectors play an understated but potent role in determining what artworks enter the culture. “The serious collector base in Australia is small, but interestingly they don’t discriminate in purchasing the work of male or female artists,” Fehily explains. “It falls on commercial galleries to nurture the emerging collectors whose holdings will be loaned or donated in the future. To do that we must widen our audience”.

Private philanthropy entails another prosaic setback: customarily, donations to public collections occur posthumously, or after years of private ownership. Important female artists being collected now might not arrive into public collections for decades. Moreover, today’s collectors were likely educated in a period when few women artists were included in mainstream histories. Self-awareness, strategic institutional acquisitions and balanced art education must bridge the interim.

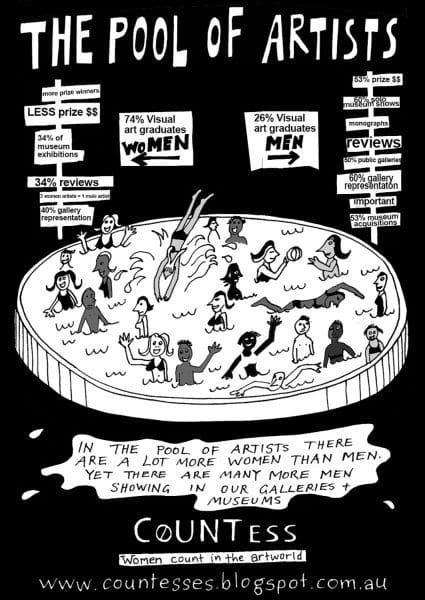

Each person interviewed for this article possessed an eager awareness of the others’ endeavours. When asked to name one key provocation for their work, all five mentioned The Countess Report. Founded in 2008 by artist Elvis Richardson and now bolstered by artist/activists Miranda Samuels and Amy Prcevich, the tiny organisation publishes sector reports, guidelines and research on gender representation. In the beginning, its output—hard data on female disadvantage —stunned us all, and trained the Australian arts sector to be attentive and responsive about its shortcomings.

The power of The Countess Report, which measured over 200 arts organisations, lies in “the hard evidence of statistical reporting,” explains Amy Prcevich. “It’s not anecdotal, which helps organisations feel accountable and means we can track progress over time.” The 2019 Report has triggered bold initiatives, including the NGA’s commitment to reach gender parity by 2020. “This is a three-person art activism project,” Prcevich stresses, “yet the evidence we provided led a federal institution to respond, loud and unambiguous. We’ve witnessed a true industry-wide response to the feelings of the community.”

The counting itself is arduous: scouring gallery labels and wordy artist statements for gender pronouns or leads on education, language and nationality. Some data points were captured too irregularly at gallery level to be published. Other insights, surrounding artists who work in a non-commercial, non-online, secluded, local or ephemeral way, remain largely invisible. The development of metrics to distinguish that data lies ahead. For now, The Countess Report is genuinely policy-aiding and stands as proof that ‘chipping away’ can make real change. Across the sector, Elvis Richardson’s efforts are viewed as a meaningful gift, continuous with a shared project that so many work on. “The Countess was our first and most impressive move into a new and more equal Australian culture,” Fehily affirms.

While parity approaches incrementally, there is already much to celebrate. Here, a list must suffice: Here We Are at the Art Gallery of NSW; Slowburn at S. H. Ervin Gallery in Sydney; the 2018 NAIDOC Week theme ‘because of her, we can’; the F Generation; feminism, art, progressions forum at George Paton Gallery in Melbourne; Reimagining the Canon at University of Newcastle Gallery, Looking abroad: all-female programming at TATE Britain in 2018 and Richard Saltoun Gallery (London) in 2019; The National Museum of Women’s #5womenartists campaign (Washington); the Guggenheim’s Hilma af Klimt retrospective (New York), its best-attended ever.

Efforts to forward equality in Australia are gathering speed, enabled partly by changing attitudes to ‘the cause’. “Five or ten years ago, a show like In Her Words would have been criticised for singling women out” remembers Poloni. In the past, getting a leg-up made some female artists uncomfortable: they felt they should beat the patriarchy on its terms, rather than playing a different, more just, game. Women artists are less likely than ever to have their work categorised according to ‘feminine’ or ‘women’s’ concerns, which makes female-focused programming more attractive and impactful. “Women are more comfortable to claim a place for themselves,” says Prcevich. “They want their work to take up space, to be installed in the culture.” Eschewing the patriarchal trope of dog-eat-dog competition, women are “raising themselves up as a whole community.”

This article was originally published in the January/February 2020 print edition of Art Guide Australia.