Sophie Penkethman-Young’s Scroll Play

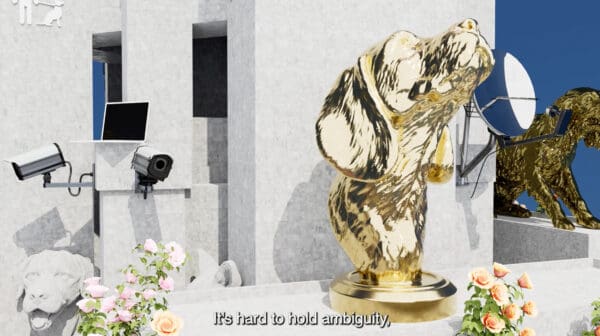

Sophie Penkethman-Young dives into the cursed, chaotic and charming depths of the online world to create inquisitive artworks exploring technology, the internet and capitalism with humour.

Alana Hunt, from the series All the violence within this, 2019, photograph, 35 mm film. Supported by The Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Alana Hunt, from the series, Expansionist Dreams (2019-ongoing), photograph, 35 mm film. Supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Elizabeth Pedler, no one is an island, 2019-2020.

Elizabeth Pedler, no one is an island, 2019-2020.

Alana Hunt, from the series All the violence within this, 2019, photograph, 35 mm film. Supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Please note due to COVID-19 restrictions, galleries across Australia are currently closed. Continuing our commitment to covering the arts Australia-wide, Art Guide Australia will continue to share articles and stories on artists and exhibitions during this time, encouraging viewers to experience art online.

Velocity equals distance over time. So runs the traditional logic of the artist’s residency: the further you travel and the longer the trip, the more productive you will be. In this widespread, familiar approach, success is measured in the volume of work made, rather than its relationship with or value to a place, community or issue. Further, the mechanism by which it is achieved is isolation; far-flung and Internet-less, the artist works up a monkish lather of silent industry, fuelled by cups of tea and countryside views.

This model works superbly for many, but its prevalence, I argue, results from a lack of imagination rather than successful examples. As artists cycle through established accommodations, very often back-to-back, there is little opportunity for them or their hosts to review the value, terms or possibilities of the arrangement. The artist gets a lot done, but remains a distant, romantic figure, rarely working in response to or for the benefit of their host community.

The question of how a residency might invigorate an artist’s whole career or meaningfully serve others is one that Marco Marcon, co-founder of International Art Space (IAS) in Perth, has been asking for two decades: “When I worked at Curtin, I’d often meet one of the university’s artists in residence at some function. I’d ask if they’d just arrived and it would turn out they’d been there for months; I just hadn’t seen them. We wanted to do exactly the opposite.”

IAS’s longform triennial program Spaced is in its fourth iteration. Responding to the program theme of Rural Utopias, a wave of artists has already begun dispersing to twelve regional WA towns, following a residency model that places social engagement at the forefront. “The word ‘residency’ is almost a misnomer,” says Marcon. “It’s more like an open studio. Work proceeds via dialogical exchange between artist and community. The artists are subject to very few requirements, but one is that they don’t close themselves off in a studio.”

The Spaced model unfolds in two stages. In the first, artists undertake 12 weeks of investigation. They are accommodated by a host or partner organisation and learn about the people, environment and economy around them. No artwork is made. A second residence is undertaken only after a lengthy break at home which “allows artists to extend their community dialogue and let their idea develop,” explains Marcon.

IAS has developed Spaced over 20 years. One early iteration took place in a “fishbowl” gallery on the main street of Kellerberrin, three hours east of Perth. “The visiting artists kept saying the same thing,” Marcon remembers; “I’ve been working here three months, and only now I’m leaving do I have a clear idea of what could be achieved!” The separation of research time from practice time quickly bore fruit. More tweaks followed; an EOI to gauge host and artist expectations, a stage-one review after which IAS gives “more money to fewer artists”, and increased flexibility around project timing.

Each Spaced program ends with a polished exhibition (Spaced 3: North by Southeast was shown in 2018 at the Art Gallery of Western Australia) and a publication. Program Director Soula Veyradier refers to the residency, exhibition and book as “three nodes”, none weightier than any other. Each is “a snapshot of what context-responsive and socially-engaged artistic approaches can look like”.

The theme of Spaced 4: Rural Utopias is a fertile brief, and Veyradier anticipates meditations on “food, production, labour, environment and how deep artistic practice can benefit the regions.” Each artist’s destination is individually brokered. Some have limited wi-fi access, others require a three-day drive. “The journey alters your sense of the world,” says Veyradier. “The artist arrives as a stranger, with no allegiances or familiarity with their new setting. They might see things which the community, in its routine, cannot, and precipitate new conversations.”

In Pingelly, 160km southwest of Perth, Mike Bianco is working alongside the University of Western Australia’s Future Farm initiative. “The conversations he’s starting around what agriculture looks like there have brought in perspectives on neighbourhood engagement, landcare and social history,” says Veyradier. On Miriwoong Country in the east Kimberley, Alana Hunt documents and unsettles what the artist describes as “the historic and contemporary violence of her own colonial culture,” focussing on the seemingly mundane activities of leisure and development. Elizabeth Pedler has been writing a blog diarising her stay at a sheep farm in Wellstead. One can read about how it feels to drench a skittish animal, the intensity of agrarian physical labour and the direction her host family is taking around sustainable agricultural practice.

The pairing of artists with hosts is not unlike matchmaking. “Each artist and community volunteered for the unknown,” says Veyradier.

“There’s no pre-determined outcome. It’s a question of timing, interest and commitment.” The candour of the IAS team is refreshing. They don’t expect every project to work out; nor do they pussyfoot, like many of us feel required to, with terms like unforeseen circumstances. Lack of commitment or resources, and personality clashes are hurdles Marcon names frankly: “Sometimes people don’t get along.”

In recent years, IAS has developed Know Thy Neighbour (KTN), an urban sibling to Spaced. “We took the global/local idea of community residency and applied it to Perth at a neighbourhood level,” explains KTN curator Katherine Wilkinson. “Each of us is so affected by patterns of habit and privilege in how well we know our surroundings. Know Thy Neighbour is a provocation for WA artists to discover and serve nearby micro-communities.” Deadlines and fixed outcomes are eschewed in favour of projects which are brief, playful and repeatable. As with Spaced, one preferred measure for success is longevity. “It’s about relationship building,” explains Wilkinson. “KTN supports artists to make ongoing links with local councils, or develop events that could be picked up by other festivals and galleries.”

Where residencies generate strong community support, they “invite a different way of articulating artistic value,” says Veyradier. There’s no attendance or sales data here: “it’s trickier, but far more rewarding to aim for outcomes like exchange of values, trust and openness to complexity.”

Spaced 4: Rural Utopias

2019—2021

Regional locations throughout Western Australia.

This article was originally published in the March/April 2020 print edition of Art Guide Australia.