Thirty-five years since the self-proclaimed Australian Cultural Terrorists stole Picasso’s 1937 painting Weeping Woman from the National Gallery of Victoria, then held it to ransom under threat of kerosene and burning canvas, the question remains: who were they?

The brazen thief or thieves apparently wandered into the gallery some time on a Saturday in August 1986, perhaps biding their time behind one of many false walls, then after closing time expertly removed the 55 x 46 centimetre artwork from a gallery wall, unscrewing and discarding its walnut frame in an alcove.

Was it an inside job? The culprit/s walked out with the painting, possibly when the gallery reopened on the Sunday, the busiest visitor day of the week, abetted by a lack of security cameras in a less technologically fortified epoch.

It wasn’t until The Age newspaper alerted the gallery on the Monday that administrators realised Weeping Woman was missing. Soon came the first ransom note from the ‘Cultural Terrorists’, decrying “clumsy, unimaginative administration” of the arts, and demanding increased funding and a new annual prize for artists under 30, to be known as the Picasso Ransom.

Victorian arts (and police) minister Race Mathews warned the culprits they would be “outcasts” if Weeping Woman was damaged. The second ransom note, accompanied by a burnt match, wrote Mathews off as a “tiresome old bag of swamp gas”.

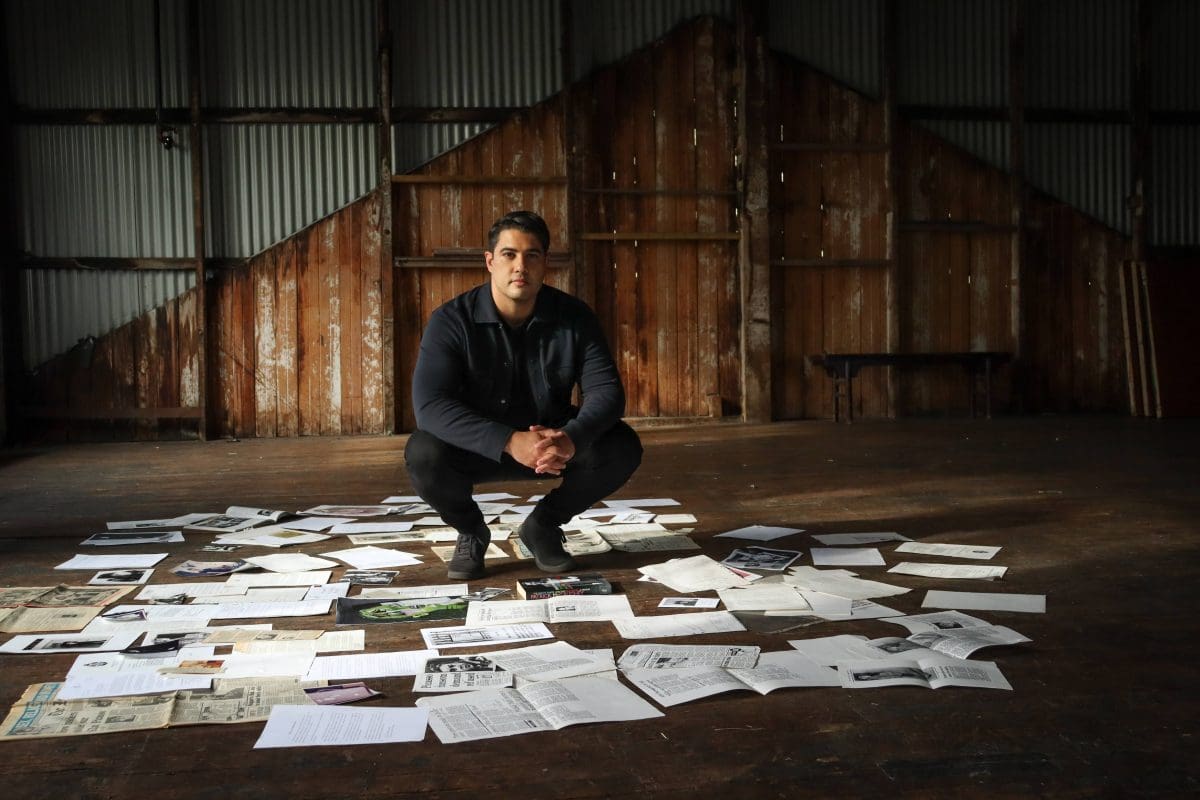

For Marc Fennell, the presenter of FRAMED, a new four-part SBS series about the theft of the painting, the question of who was hurt by this great art heist is more interesting than speculation on who stole the Picasso. “Everybody you talk to absolutely knows who did it,” says Fennell. “The problem is none of those people can actually agree on who it was.”

Fennell was born in 1985, the year the then NGV director, Patrick McCaughey, purchased Weeping Woman for $1.6 million, then the greatest amount an Australian public gallery had ever paid for a painting, sparking cultural cringe in the media coverage.

The Catholic conservative commentator B. A. Santamaria, who hated Picasso’s work, wrote “if the Australian Cultural Terrorists have really disposed of Weeping Woman, they should not so much invite censure as be rewarded with the Order of Australia”.

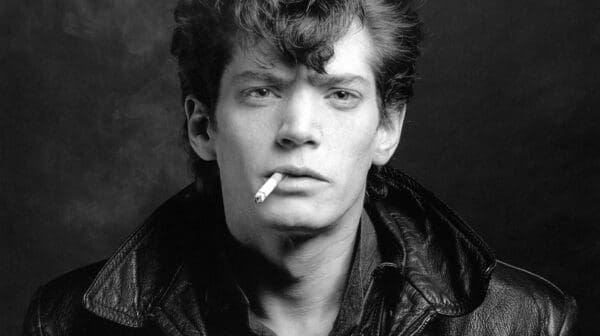

The work’s greatest value perhaps is as a postscript to Picasso’s contemporaneous anti-war masterpiece Guernica, elaborating on a detail of a woman screaming while holding a dead baby. Bathed in acidic green and purple, Weeping Woman depicts Picasso’s lover, the artist and photographer Dora Maar, and is one of four known oil-on-canvas versions of the subject.

Fennell says the theft was used to settle old scores, with accusations being left against various people on an anonymous tip line that was set up by police to find leads. Gallery community members took matters into their own hands, going directly to artists with “faulty” information, with a “devastating” impact on artists.

“What I’m more interested in is the chain reaction of the crime,” says Fennell. “Some people still view it as a very entertaining prank, some as an elaborate act of performance art. Some people review it as revenge on Race Mathews and Patrick McCaughey.

“But it’s also a weird chapter that actually ruins a whole bunch of lives, and those people never got front pages. Patrick [McCaughey] talks about it in his [2003] book [The Bright Shapes and the True Names] as a ‘victimless crime’, and that’s what has always stood out to me, because I don’t think it is a victimless crime.

“There were people who had the finger pointed at them but had nothing to do with it, and yet this strange crime has come to define their lives through no fault of their own.”

In the first episode of FRAMED, former NGV chief conservator Thomas Dixon says of the theft: “I have to say at the time we were shaking in our boots.” However, a little more than two weeks after the theft, on 19 August, Weeping Woman was found safely deposited in locker 227 at what was then known as Spencer Street railway station, now Southern Cross, after a phone tipoff to then Age journalist Margaret Simons.

In his memoir, McCaughey criticises the gallery security attendants as a “belligerent lot” who “felt blamed” for the theft, taking industrial action after he “promptly took their chairs away so they had to walk round for their two-hour shifts and not repose in lethargic stupor”.

McCaughey named an artist whose studio he called into after a tipoff, though he “surmised” the artist’s innocence. “Who took the Picasso?” McCaughey concluded. “Who were the Australian Cultural Terrorists? I have no idea.”

That named artist later told writer Anson Cameron for Cameron’s book Stealing Picasso that he had been “set up” and that details of McCaughey’s recollection of their meeting were “bullshit”.

Did Fennell and his team approach McCaughey for an interview? “We’ve had communication with Patrick,” he says. “I think Patrick would prefer that this thing doesn’t get talked about, is my impression. There’s a whole range of people who didn’t want to talk about it, and Patrick is one of them …

“McCaughey bore the brunt of it in the moment … the impact on him and his family was huge, and I kind of don’t blame him for not talking [now], to some extent.”

What about the minister, Mathews, whom the ransom letters targeted?

“He’s alive but he’s very old. We had a lot of communication with his wife about this. There’s a lot of people we talked to who, in the end, felt really damaged.”

FRAMED premieres on SBS on Demand on Sunday 26 December.