Material curiosities: Primavera 2025

In its 34th year, Primavera—the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia’s annual survey of Australian artists 35 and under—might be about to age out of itself, but with age it seems, comes wisdom and perspective.

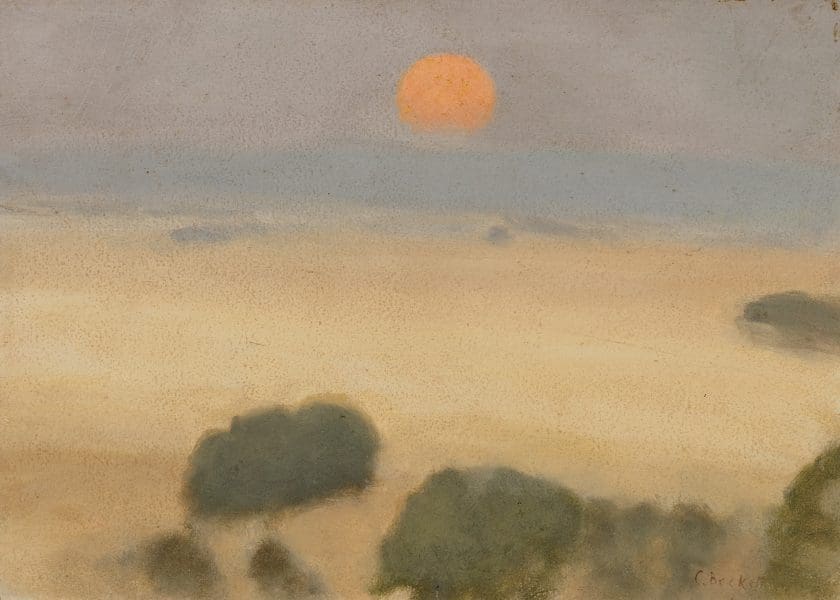

The atmospheric haze in Clarice Beckett’s paintings has always been imagined as a weather phenomenon—the most exquisite, oppressive fog. The Melbourne artist, who died in 1935, was part of a localised painting movement that banished hard boundaries between objects and the air that surrounds them. Yet curator Tracey Lock, who has brought together Clarice Beckett: The present moment at the Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA), has a different reading: it’s not mist or fog, and it never was—it’s something much more otherworldly.

Beckett is one of the few tonal painters—those who captured natural life with a sense of coloured atmosphere or mist—still cherished today, even surpassing the reputation of her teacher, artist Max Meldrum. Now recognised as a leading modernist, she spent her life in Melbourne and its surrounds, capturing commonplace scenes with her trademark ethereal style, before dying of pneumonia at the young age of 48.

Whereas other tonal painters focused on still-life genres, Beckett painted outside: bitumen roads, black cabs, telephone poles, streetlamps, all suffused with the tonalist’s signature blur. With her plein air appreciation of modern life, many have categorised Beckett as an unfortunately late Impressionist, decades behind in the international avant-garde. Yet Lock thinks this idea of Beckett as a conservative modernist needs to change; there’s an experimentation in her work that has, until now, been little commented upon. “We need to prepare ourselves for understanding Clarice Beckett as being of international significance,” says the curator. “She’s big guns.”

On trips to the conservation labs at AGSA, curators and conservationists alike marvelled at Beckett’s paintings under the microscope. “Looking at the painted surface, it blows your mind,” says Lock. “Her technical ability was phenomenal.” While nobody denies Beckett’s exquisite skill, Lock’s reframing of Beckett as a spiritual modernist is more daring.

This brings us back to the mist, the atmospheric haze that can paradoxically appear in Beckett’s overcast pictures, as well as her summer beach scenes. Historically, Lock explains, critics have said “really disparaging things about her getting lost in her own fog.” Lock recasts Beckett’s dissolving forms as a “vibratory sensibility” that alludes to an “otherworldly” place. The mist, then, is better understood as a vibration between space, distance and time; a haziness between one realm and another.

Through recent historical revisions, we are only just beginning to appreciate the clandestine streaks of spiritualist thought that ran parallel to modernism during Beckett’s lifetime. Spiritualism is the general term for a belief that other realms—particularly the realm of the afterlife—exist and are visible in our own everyday world. Séances, automatic writing and entering trances were spiritualist practices, as was a Westernised version of meditation, derived from Eastern religions such as Buddhism and Hinduism.

Beckett herself read spiritualist materials and was active in mystical circles: her friends included artists who were either Freudians, Bohemians, or card-carrying spiritualists (like the prominent family of artist Alexander Colquhoun). This network extended to local artist couple Christian and Napier Waller, and visiting occultist architects Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin. By drawing this web of spiritualism around Beckett, Lock has made a case for the existence of mysticism in both the artist’s life and in her painting.

This re-thinking of Beckett as both a modernist and mystic is mirrored at an international level, with recent exhibitions reappraising the works of Wassily Kandinsky, Hilma af Klint, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Piet Mondrian. Unfortunately, due to her unexpected death, and the long period of critical obscurity that followed, very little is known about Beckett’s actual beliefs and her inner life. There are no existent letters or diaries written by the artist. “We’re dealing with fragments, shards,” says Lock.

What does remain is a portion of her oeuvre, the majority of which was destroyed after Beckett’s death. Lock, however, is adamant that the remaining paintings– 130 of which will be on show—are all you need to understand Beckett’s philosophy: “Let’s bring it on, put a Beckett up in an international context with those other artists. I can assure you, [she] will hold the wall.”

Dawn and dusk are Beckett’s signature times of day. These ethereal ‘golden hours’ demonstrate the artist’s preoccupation with time appearing suspended, mutable. Because Beckett’s work was remarkably consistent (and because the artist showed little interest in writing the date on her work) her early, mid and late style cannot be discerned. “From her earliest to her last works, there is very little change,” observes Lock.

Turning this potential obstacle into a strength, Lock organised The present moment as if the paintings represented a single, eternal day. It begins in early morning and travels all the way through late evening.

Befitting Lock’s spiritualist interpretation, the exhibition presents Beckett’s layered relationship with time and the visible world. Between each section is not a doorway, but a rounded portal, through which the visitor is invited to mark the changes in the day—but where years and decades are irrelevant. Stepping through each portal, all of Beckett’s days stretch into one as she offers us the universal dawn, the universal dusk.

The present moment

Clarice Beckett

Art Gallery of South Australia

27 February—23 May

This article was originally published in the March/April 2021 print edition of Art Guide Australia.