Material curiosities: Primavera 2025

In its 34th year, Primavera—the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia’s annual survey of Australian artists 35 and under—might be about to age out of itself, but with age it seems, comes wisdom and perspective.

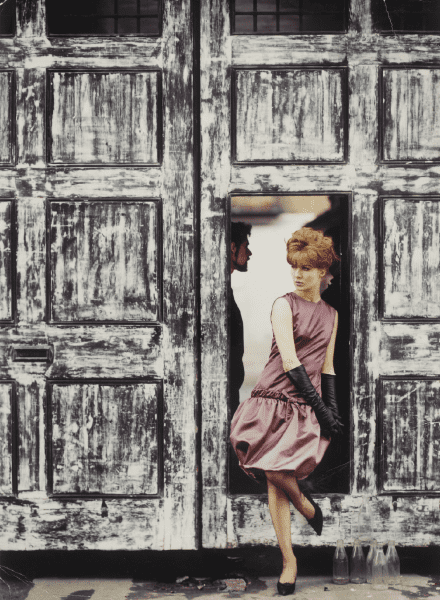

In 1965, English model Jean Shrimpton wore a minidress to the Melbourne Spring Races and caused a sensation. Photographs of her scandalous outfit hit the front pages. A simple white shift, hemline just above the knee, the dress appears laughably demure to contemporary eyes—but it was a clarion call of liberation to young Australian women, stifled by the stuffy conventions of the era. Eschewing the compulsory hat, gloves and stockings, Shrimpton’s free and easy appearance was a revelation, and Australian women embraced it swiftly. By the time the 1966 Flemington Races rolled around, hats and gloves had been tossed away, and hemlines had risen even higher. Fashion would never be the same.

At the helm of this global movement was British designer Mary Quant. Championing “relaxed clothes, suited to the actions of normal life,” Quant is widely accepted as popularising the miniskirt and revitalising women’s dress. Characterising 1950s Britain as “railway stations and Typhoo tea, stockings and suspenders,” Quant led a revolution in colour, style and comfort. “I didn’t have time to wait for women’s lib,” she later said.

Originally staged at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum (the V&A), and now travelling to Bendigo, Mary Quant: Fashion Revolutionary is a major survey of Quant’s remarkable career that radiates the designer’s buoyant personality. “She was female, she was young; she represented the triumph of youth and freedom,” says Bendigo Art Gallery curator Emma Busowsky Cox. Woven throughout the exhibition are stories, photographs and clothing from the millions of women who adopted Quant’s groundbreaking designs and made them their own.

The survey begins in 1955 with Quant’s first London boutique, Bazaar, which was something of a phenomenon. “If you think about the way shopping occurred before then, it was a very formal kind of experience,” says Cox. Harrods, for example, was a stolid world of hats, gloves, and demure cream teas. In contrast, Bazaar launched with a party (where all the stock immediately sold out), stayed open late at night, and featured extravagant, arty window displays with mannequins in lively poses and “crazy things like having a lobster on a lead.” Two years later Quant actually opened her second store directly opposite Harrods—a bold challenge to the establishment.

Quant’s designs drew inspiration from surprising places. She reinvented styles from menswear and children’s wear—tailored trousers and jackets, pinafores and Peter Pan collars—and recast them as fashion for contemporary young women: fun, flirty, and easy to move in. In addition to ever-rising hemlines, she popularised coloured tights, reinvented the drab raincoat in a rainbow of hues, and experimented with new materials like PVC, lurex and jersey. “Stretch jersey was quite a new fabric then,” Cox says, “and this is a hallmark of [Quant’s] design—liberating from that corseted waist to a shorter hemline and stretch fabrics, which allowed women to move and run and jump and be more free.”

A significant part of Quant’s success lay in her determination to make clothes available at a wide range of price points, effectively democratising fashion.

She quickly embraced mass production with the popular Ginger Group line, which featured colourful shift dresses and separates at prices accessible to ordinary working women—even at a time when women’s wages were routinely a fraction of men’s. In 1963 Quant went a step further when she signed a deal with Butterick, a notable producer of sewing patterns, enabling home dressmakers to produce Quant designs cheaply and adapt them to personal taste.

In the lead-up to the original V&A exhibition, adopting the slogan ‘We Want Quant’, the Victoria & Albert Museum undertook a widely-publicised search for Quant pieces to bolster their existing collection. They received over 800 responses from around the United Kingdom, spanning the gamut of high-end couture, High Street fashion, and homemade items produced from the Butterick patterns. Women sent in photographs of themselves wearing treasured Quant pieces in the 1960s and 1970s, from wedding dresses to raincoats and miniskirts.

Many of these original pieces have become features of the exhibition, often retaining additions by their former owners: one Ginger Group minidress sports a hemline raised even further by its wearer. It is notable that these clothes, often acquired by saving up hard-earned wages, had been carefully stored for decades. “These were garments that were more affordable, but they were also treasured by women,” Cox says. “They were just a big part of women’s lives.”

Mary Quant: Fashion Revolutionary

Bendigo Art Gallery

20 March—11 July

This article was originally published in the March/April 2021 print edition of Art Guide Australia.