Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

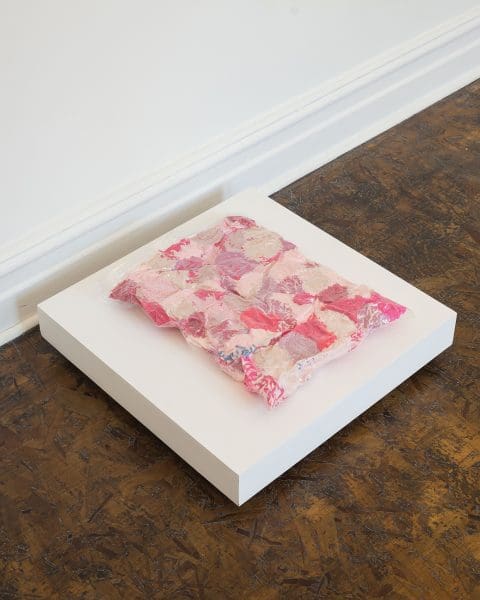

Michele Elliott, tender cloth and scarf, 2019, cotton, silk, botanical material.

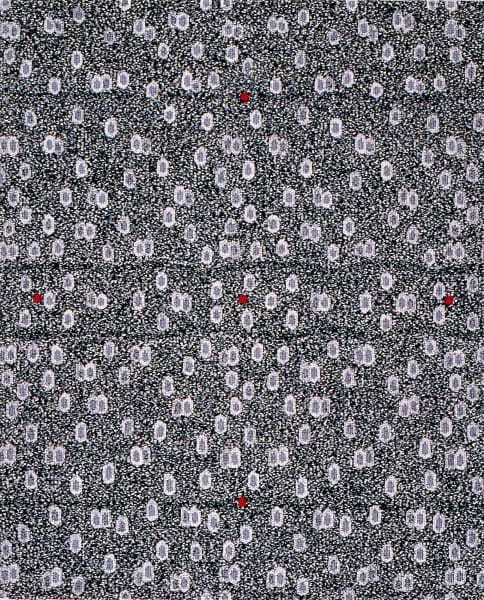

Michele Elliott, the confidantes (inamorata), 2018, giclée print on Hahnemuhle rag, 40 x 43.5 cm. Photo: Frances Mocnik.

Once relegated to ‘merely craft’, textiles are suddenly everywhere. Over the past 10 to 15 years, artists and hobbyists alike have been turning in great numbers to textile processes, bolstered by a spate of large international exhibitions of seminal 20th century fibre artists like Lenore Tawney, Anni Albers, Gunta Stölzl, Harmony Hammond, and Sheila Hicks. And, if social media is anything to go by, this gravitation towards the soft, the stitched and the handmade has only increased during recent periods of lockdown, where feelings of stress and anxiety have seen people turn to the slow, repetitive, comforting processes of knitting, embroidery and quilting to get them through.

Why are we so drawn to textiles? Is it because, when our fingers touch cloth, they’re sensing something deeper—an emotional resonance, a history held in fibre?

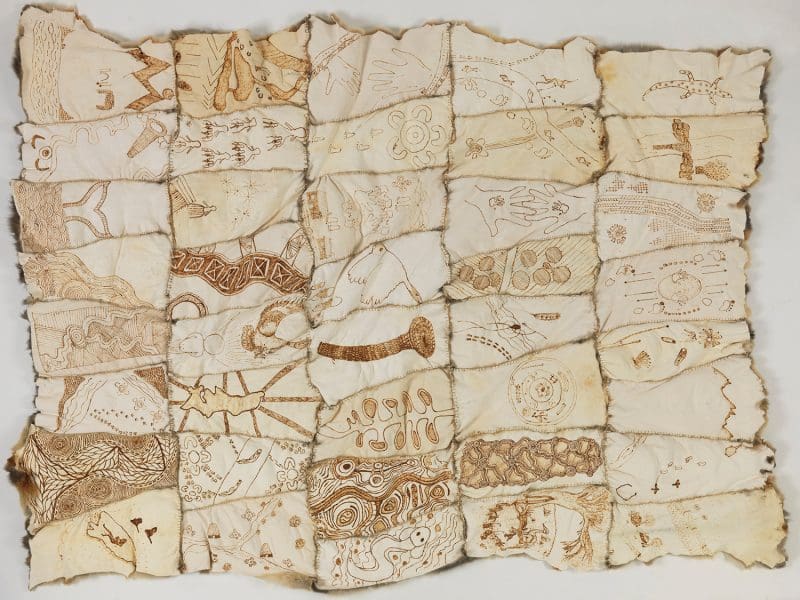

Not so long ago, textiles meant work—a lot of it. A simple woollen garment would require weeks of labour to make from scratch. Shear a sheep, wash a fleece, comb it lock by lock to align the fibres, spin it into yarn, weave or knit into cloth. Or take the possum-skin cloak, which was ubiquitous throughout south-eastern Australia in pre-colonial times: it might take up to a year to collect the 50-plus skins for an adult cloak, which were later dried, sewn together with thread prepared from from kangaroo-tail sinew, painstakingly incised with intricate designs, and rubbed with ochre. These processes are slow and laborious in a way that’s hard to fathom when clothes now spring ready-made from the internet—but they’re also part of a rich web of knowledge, significance and connection to place.

In 2020 we are both physically and spiritually separated from the intricacies of textiles. As the seminal Bauhaus weaver Anni Albers bemoaned in 1965: “Our materials come to us already ground and chipped and crushed and powdered and mixed and sliced, so that only the finale in the long sequence of operations from matter to product is left to us: we merely toast the bread. No need to get our hands into the dough.”

But it’s this very disconnect, at least in part, that’s driving the current surge of interest: a desire to shift our hands from the keyboard to the dough. Sustainability, too, is at play, as more people become aware of the monumental toll that overproduction (and overconsumption) of textiles is taking—both on the environment and on those tasked with producing our cheap, convenient clothing. And scholarship and appreciation of First Nations cultures, including many living crafts, is on the rise in institutions and mainstream culture alike.

Of course, textiles have long been nominally part of the art world, particularly since the 1950s Fibre Arts movement and the wider craft revival of the 1970s. In Australia, any preconceptions of tapestry as stodgy and staid were exploded when Polish artist Magdalena Abakanowicz visited Sydney and Melbourne in 1976, exhibiting her groundbreaking sculptural installations at the Art Gallery of New South Wales and the National Gallery of Victoria.

The influence of Abakanowicz’s work was profound. “Suddenly there was a movement towards much more sculptural pieces,” recalls Melbourne-based artist and master weaver Sara Lindsay, who in 1976 was just beginning her textiles career. “And at the same time, potters were not making functional pots any more—they were making big vessels or figurative work.” This shift in focus from function to form and concept—the notion that ‘craft’ could be experimental, and convey big ideas—took hold in a real way. “More and more people were starting to use textiles in an expressive way to talk about ideas, personal ideas: ‘the personal is political’, gender, feminism,” says Lindsay.

Tellingly, the Abakanowicz exhibitions were funded by the Australia Council’s Crafts Board at the time, rather than the separate Visual Art Board. It’s only fairly recently that artists working in these mediums have had their work widely accepted as more than ‘craft’—often derided as mere decoration without concept—and the conversation expanded beyond that of ‘women’s work’. “We were still trying to nudge our way into ‘visual art’—not being told to go back and do our sewing in our corner,” Lindsay says of exhibiting textile art in Australia well into the 1990s. “It was a very male domain.”

Curiously, and perhaps a little ironically, there is an idea that this greater aesthetic appreciation of textiles has occurred partly due to more male artists creating art with fibres. As the American curator Jenelle Porter has written, “…it is often the case that when male artists knit or sew, it is considered transgressive, a defiance of traditional gender roles—it is not considered craft.” And in recent years, institutional recognition of artists who are not ‘male, pale and stale’—women artists, artists of colour, queer and non-binary people, Indigenous and First Nations artists—has helped this conversation develop further.

As renowned Gunditjmara artist Vicki Couzens knows, fibres also contain thousands of years of history and tradition, from warmth to carrying vessels, from birth to death. When I spoke with her, Couzens described her profound encounter with a 19th century Gunditjmara possum-skin cloak, in the stores of the Melbourne Museum. “I just felt this very visceral and very deep connection. We were all gathered around there, and you could feel the Ancestors enter, and they came and surrounded the group. The hair on my arms was tingling—their presence was so powerful.” Charged with a strong conviction that cloak-making must be returned to the community, Couzens is one of a core group of practitioners who, over the past two decades, have been committed to doing just that.

A possum-skin cloak would stay with you throughout your life. From being wrapped in one or two skins as a baby, your cloak would grow with you as more panels were added, each inscribed with designs recording your specific history, Country and family. Women would carry their babies in possum-skin cloaks, or stretch them across their knees for drumming. And for many mobs, including Gunditjmara people: “You’re also buried in your cloak,” says Couzens. It’s a garment heavy with meaning, deeply practical, and inherently sustainable.

Now, cloaks are being made all across southeastern Australia, by numerous language groups, communities, families and individuals; physical embodiments of Country, ancestry and knowledge.

Embodiment, here, is key. As artist Michele Elliot says: “I think there’s a few things going on with this gravitation towards textiles, because it does have that ability to speak about the body and about the experience of being human.”

During 2017–2019 Elliot was an artist-in-residence at Tender Funerals, a deeply unusual not-forprofit funeral service in Port Kembla, New South Wales, where the human body goes hand in hand with textile practice.

During her time at the community-run funeral home, which places great emphasis on sustainability and affordability, Elliot began making an ongoing series called tender cloths: lengths of muslin fabric hand-dyed with funeral flowers. These floral arrangements, she explains, are generally “just used for the occasion of the funeral. And then they’re often thrown away.” After being exhibited, the cloths were given to the mortuary for use during “the final rituals” for those who might come to Tender without any family, as a form of additional care.

In the course of her residency, Elliot also worked directly with bereaved families to develop specific rituals for ceremonies and wakes. In one instance, for the funeral of a longtime quilter, friends and family selected pieces of fabric from her stash and turned them into cloth ribbons in shades of purple—“her colour”—to be affixed to her woven casket.

On another poignant occasion, Elliot spent several hours with a young person whose parent had died, working together on an embroidery. She describes how the time spent stitching helped this child gather the strength to say goodbye, finally entering the mortuary and placing the finished piece on the parent’s body.

And as part of an aftercare program for families, Elliot runs a sewing circle, another space to perform tangible rituals; to move forward, moment by moment, stitch by stitch.

From one perspective, it might seem like this is exactly the kind of tactile connection at risk of being lost in a digital world. Yet Perth-based artist Carla Adams doesn’t exactly see it that way: “When you go on your computer, that’s happening in real life,” she points out. “It’s not like some separate world that somehow doesn’t exist beyond and outside of the screen.”

Much of Adams’s work engages with dating apps and video chat forums, exploring the dynamics of relationships through the screen. The titles of her large-scale woven works and wall sculptures document the frequent misogyny and downright poison of these fleeting encounters—‘wanna get gang raped?’ and ‘fat bitch’ are just some of the messages she’s received. In response, Adams has fashioned portraits of her online abusers using materials like fluorescent pink bondage rope, freshwater pearls and stick-on gems. “I feel like the textile process links the digital and physical worlds,” she says. Even more fittingly, computers operate using a binary code—zeroes and ones—which is a direct descendant of the punchcard system of the Jacquard loom.

As someone “obsessed with stories and narratives,” Adams explains that “the slowness of the textiles gives me time to unpack or create a narrative around this very short encounter. Even if it’s a negative encounter—through that time spent, you can start to make sense of things and package them.” Adams’s caricatures of these men who stare contemptuously from the screen—their faces crudely rendered, yet lovingly adorned—are stitched together to unravel the male gaze and reverse it.

Drawn from the digital, their power is in their physicality: “Textiles are just so much about the body, inherently. They hang in such a way that they’ve got a presence, a heaviness or a heftiness to them.”

The presence—the heft—of these textiles remains long after the works are physically elsewhere.

We can’t help but be drawn to fibre. The span of human history is dense with it—adorning our homes, carrying precious objects, wrapping our bodies, holding us together.

Skirts Project

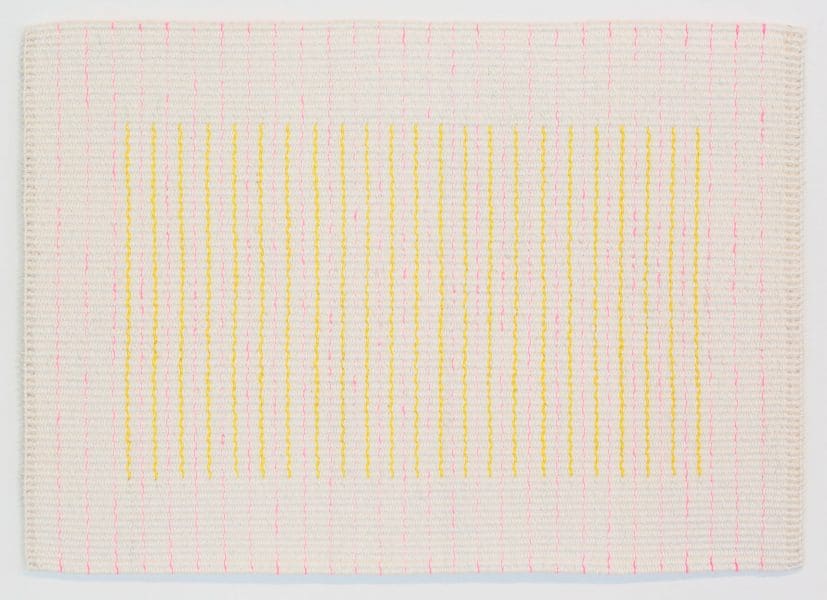

Sara Lindsay

Ongoing

Fabrications

(featuring work by Michele Elliot)

Wollongong Art Gallery

15 August–15 November

Sorry I was / am too much

Carla Adams and Albert Tucker

Art Gallery of Western Australia

12 December—15 March 2021

Gunditjmara possum skin cloaks from 1892 and 2019 are currently on display in the First Peoples gallery at Melbourne Museum, and in the online collection. Museum opening hours are subject to Covid-19 restrictions.

This article was originally published in the November/December 2020 print edition of Art Guide Australia.