Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

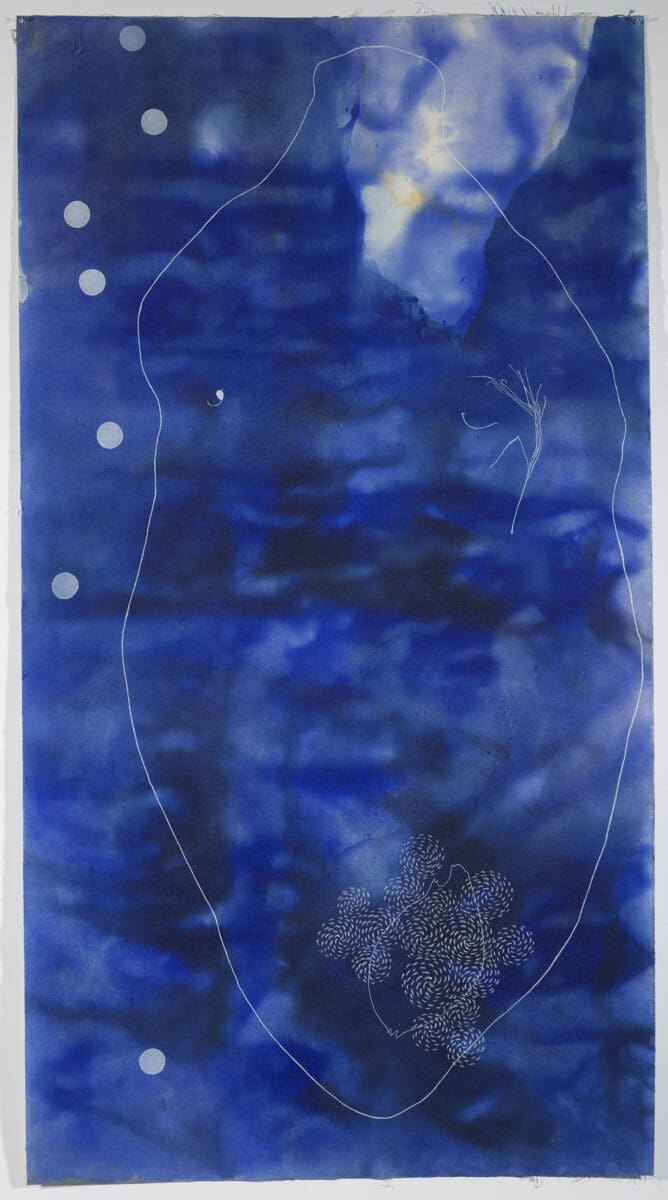

Having worked across an array of art forms since the early 1980s, Judy Watson continues to reserve a special respect for drawing—putting pencil to paper, she says, involves an exchange where something vital travels between artist and artwork. A powerful charge is transmitted.

One of the joys of looking back on her two-dimensional works is the recollections they evoke. “It is like a body memory,” says Watson. “I remember—not every time, but a lot of the time—where I was, what it smelt like, what was around me, what I was looking at. Whereas if I look at a photograph, I don’t have that same residue of memory and recognition.”

In recent times, Watson has had much to recall as she and QAGOMA curator of Indigenous Australian art Katina Davidson have amassed more than 120 of Watson’s works for a new exhibition surveying her career so far.

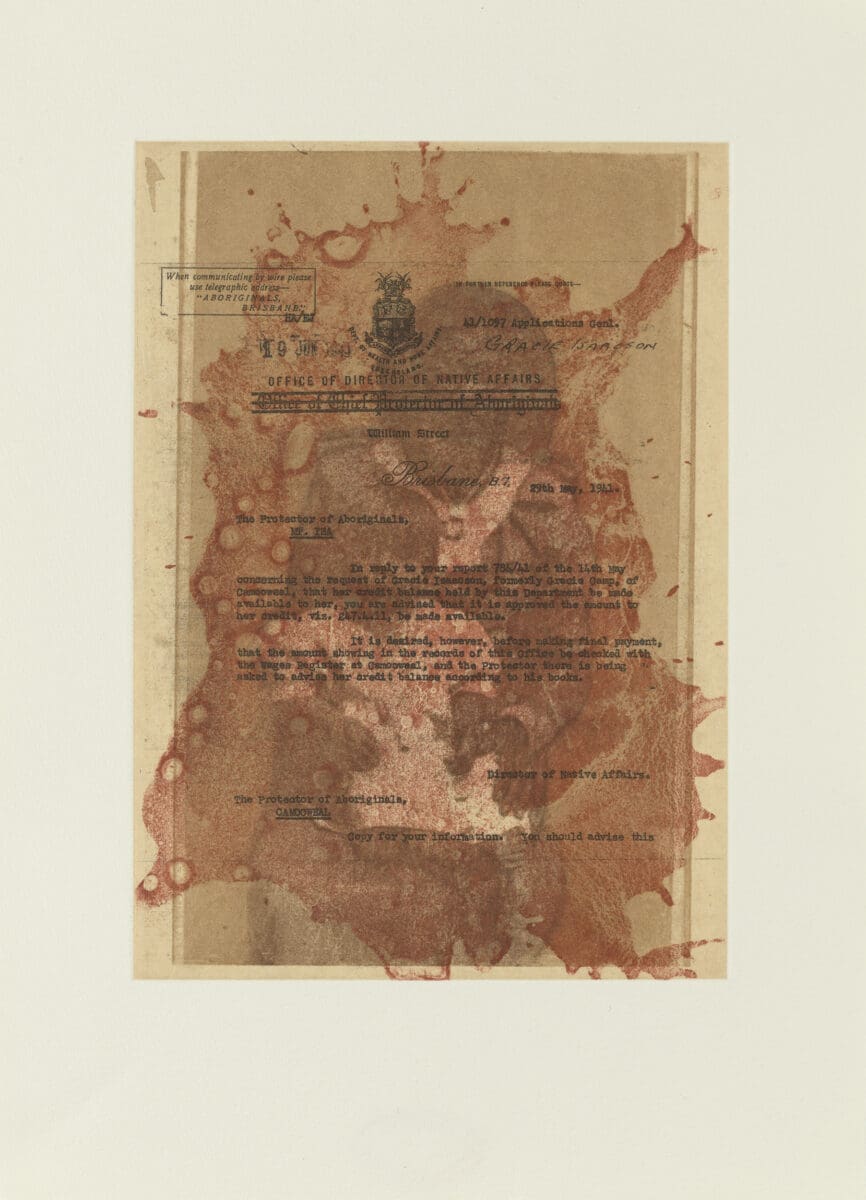

Davidson has traced Watson’s deep engagement with her Waanyi Country in North West Queensland, as well as her abiding interests in environmentalism and feminism, and her persistent exploration of truth-telling through activating archival collections. Amid all this, Watson has charted historical, emotional and psychological states with carefully layered artworks that evoke grief, hope and multiple histories.

Watson’s powerful, research-based stories in many ways concern the effects of colonisation on Australia’s First Peoples. As QAGOMA director Chris Saines has noted, Watson’s work holds both historical and present-day injustices to account, and “is not only a persistent and haunting requiem for cultural loss, but also an unbowed declaration of cultural reclamation”.

“Haunting” is a state that intrigues Watson. Discussing a recent public artwork in which she was exploring ideas around cultural retrieval, acknowledging the objects and language that had been taken from that space in the past, Watson says the challenge has been to not only embed learning, curiosity and aesthetics within the work, but to strive to encourage viewers to feel something about it as well.

“That is the sort of work I respond to best. Whether it is text, film or music, it is something that calls you in. If I can achieve a ‘haunting’ and it becomes subliminal, it is as if the viewer swallows the work: it goes inside their body before they understand what has happened, and then it is there. It is like osmosis.”

Very early in her career, Watson worked in a sign-making factory while saving up to go to art school; she has also had much experience making print posters. “So I understand all that and how it works: you see a sign or poster, you ‘get’ it and then you keep going. Whereas something that draws you right in, for whatever reason: that is what I come back to.”

Watson has had enduring success internationally and in Australia. She was in QAGOMA’s first Asia Pacific Triennial (1993) and represented Australia. at the 1997 Venice Biennale alongside Emily Kame Kngwarreye and Yvonne Koolmatrie. Her work is inmost collecting institutions’ holdings, and she has been commissioned for many public art works amid her daily practice producing paintings, prints, sculpture, installations, video and, of course, the drawings that underpin it all.

Curator Davidson says she has been privileged to spend so much time with Watson in the artist’s Brisbane studio, conversing about her four decades of creativity. While Davidson says the survey has thematic strands, what is evident is how they are all entwined by Watson’s ability to continually see the world with fresh eyes and engage with socio-political and environmental concerns through a poetic lens.

Davidson notes that the Waanyi are known as “running water people”, with water at the heart of so much of Watson’s work, as are family memories and a strong matrilineal current stretching into the distant past. Watson inhabits that heritage with vitality and speaks about the importance of passing things on: one of her great pleasures is during the making process when she has paid helpers around her (she has a long history of engaging a wide variety of family and colleagues as assistants)

This work may involve, for example, twining raffia strands together, or other manual production. There, together, they chat, eat good food, listen to podcasts and music, and have fun—but something else manifests, too. “It’s a very collegiate, communal atmosphere, and while you are doing things with your hands and your body, you might also be transmitting knowledge. A sort of mentoring is enacted.”

That is implicit in the title of the exhibition, which references a line of poetry written by Watson’s son, Otis Carmichael, proclaiming that “tomorrow the tree grows stronger”. As Watson says, passing things on is a beautiful concept and practice, but the next generation will take it and do with it what they will—just as the running waters of her own history have nurtured and informed her own way of making art, with work that sensitively guides viewers into a poignant aquifer of emotive and spiritual power, to what lies beneath.

mudunama kundana wandaraba jarribirri

Judy Watson

Queensland Art Gallery (Brisbane/Meanjin)

23 March—11 August

This article was originally published in the March/April 2024 print edition of Art Guide Australia.