Piercing the veil

A new exhibition at Buxton Contemporary finds a rich complexity in the shadowy terrain between life and death.

Bhenji Ra, Talking Bodies, 2019. Performance for Late Night Library (2019) at Surry Hills Library. Photograph: Katy Green Loughrey.

Bhenji Ra, Talking Bodies, 2019. Performance for Late Night Library (2019) at Surry Hills Library. Photograph: Katy Green Loughrey.

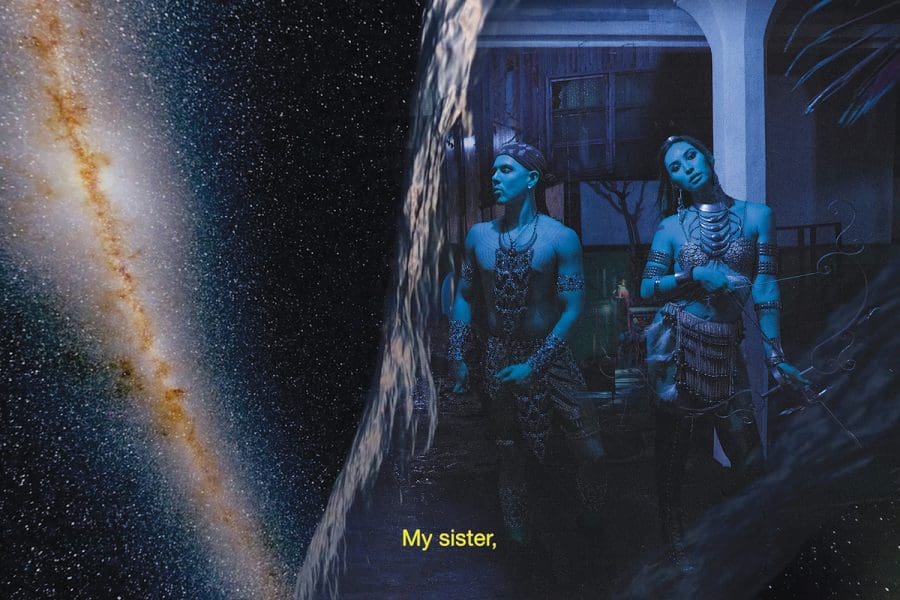

Club Ate, ExNilalang, 2015 (video still) Courtesy the artist.

Club Ate, 2019, Courtesy the artist.

Currently the Biennale of Sydney is closed until further notice. You can find out more about Club Ate and their work here.

“I think dance has always been the answer for me,” says Bhenji Ra of her interdisciplinary art practice. “Dance has always been innately queer, and accessible in the way it can slip between gender and class. There’s lots of power and resilience in that.”

Ra has built a significant profile over the past several years. After an initial training in classical Western forms that she found stifling, moving outside of the “patriarchal structures” that define how the body functions in dance schools has given her space to flourish. “My body was trying to strive to fit into this very masculine, muscular and virtuosic form. I’m surprised I lasted as long I did at dance school—I didn’t have a voice.” Now, Ra brings together dance, community building and politics in her practice. In a way that questions dominant histories and narratives, and brings together people from the margins, she provides platforms for others to find a voice, and in so doing also carves out a place for herself.

In 2015, Ra developed the work Bowling Club Medley for Underbelly Festival on Cockatoo Island. It speaks volumes to the way that she uses dance to think about community and the transmission and creation of culture. She collaborated with a social group of Filipina women who called themselves the Bay Angels. The Bay Angels would regularly get together to do line dancing in rural bowling clubs. In matching white cowboy boots and hats, Bhenji and the Bay Angels danced a medley of social dances and folk-inspired Filipino dances in an extended performance.

“It was such a form of togetherness and collective joy, and it was a way to put value on that. Line dancing in rural bowling clubs felt like a way that Filipino culture had transformed in this new Australian context.”

Queer and trans histories are fundamental to Ra’s work, as is this sense of finding space for herself and others as a mode of survival. Ra has been a central figure in developing Australia’s local vogue scene through Sydney’s annual Sissy Ball. For the uninitiated, ball culture is a form of performance and resistance that has grown out of New York queer scenes since the 1920s, with mostly black and Latinx folk dancing, walking, voguing, competing on a runway. Both individual participants and groups (known as ‘houses’) vie for categories like best dance, movement, fashion and flair. From those original roots ball culture has made its way to pockets of QTPOC (Queer Trans People of Colour) around the world.

As the Mother of the House of Slé, a vogue house in Western Sydney, Ra is a senior figure who helps newer girls come into the fray. Ra has fought to create space for many; ball culture and voguing offer a genealogy and tradition to the folks who find them.

“Being a house mother is about creating a system of care and guidance for young women and trans folk and queer folk that are coming up, and giving them what maybe I never had as a young person. Allowing them to feel like they had space and freedom to express and to go after what they want in life. And just giving them permission.”

Ra grew up in rural South Coast New South Wales in a Filipino working-class family. ‘Otherness’ finds you in regional Australia when you’re queer and brown, and it’s something that Ra understood from an early age. She also recognised that this ‘Otherness’ could be weaponised into a tool of resilience and something to be fiercely proud of. A large Filipino community has flourished in the area: “You can’t have that many Filipina women around you and not feel protected.”

For the 22nd Biennale of Sydney, Ra is collaborating with Sitti Obeso to develop a performance lecture. Obeso is a Tausūg elder and a master of a dance form called Pangalay, which originates in the Southern Philippines. Pangalay has roots in pre-colonial Philippines, and is a classical form defined by slow and graceful movements, with a focus on the hands and the use of ornamented metal fingernails.

The two met when one of Ra’s cousins married into Obeso’s extended family; Ra has familial and cultural ties to the Southern Philippines, and is interested in exploring the transmission of culture and tradition.

“I felt that from when we started working together, she [Obeso] saw me as how I was, recognised my gender variance and all that comes with it—who I am as a second-generation Filipina. There was no hesitation or resistance to it.”

The performance will focus on the ‘in-between’ of the passing down of cultural knowledge; of the way that it shifts and changes as different generations are brought into the fold—as people come to find a place in a genealogy and a living body of knowledge.“It’s sort of like that Aunty vibe, you know?” Ra says of her relationship with Obeso. “She sends me chain letters via Facebook messenger, saying ‘Allah bless you,’ things like that—looks out for me and tells me about the sort of responsibility that comes with dancing Pangalay.”

These sorts of relationships where cultural knowledge, traditions and history can be transmitted have been central to Ra’s practice over the last several years. The way that she interrogates them through dance unpacks that way that individuals can find a place and a community in larger narratives— especially for those who are usually written out of history.

Club Ate: Bhenji Ra and Sitto Obeso

3 June & 6 June, 12 pm–1.30 pm

Powerhouse Museum

22nd Biennale of Sydney: NIRIN

This article was originally published in the March/April 2020 print edition of Art Guide Australia.