Piercing the veil

A new exhibition at Buxton Contemporary finds a rich complexity in the shadowy terrain between life and death.

Abdul-Rahman Abdullah, David, 2018, edition of 6 plus AP concrete, enamel, oxide, 390 x 480 x 310 mm. Photo: Abdul-Rahman Abdullah, courtesy of the artist and Moore Contemporary.

Alexander Lotersztain, QTZ Footrest, Lounger, Lounger without headrest, and Table, 2016, concrete. 440 x 520 x 657 mm, 1123 x 650 x 804 mm, 757 x 650 x 804 mm, 410 x 392 x 390 mm. Photo: IVANKA Concrete.

Anna Horne, Hardly Soft (red), 2018, concrete, 1000 x 300 x 300 mm. Photo: Grant Hancock.

Candlepas Associates, Punchbowl Mosque, 2018, Prayer Space. Photo: Rory Gardiner.

Durbach Block Jaggers, Tamarama House, 2015. Photo: Tom Ferguson.

Inari Kiuru, Memory of the sea, interactive table sculpture, 2017, various arrangements of the nine parts. Photo: Inari Kiuru.

Jamie North, Remainder No.10, 2017, cement, blast furnace slag, marble dust, steel, Pyrrosia rupestris (rock-felt fern), 330 mm diameter. Photo: courtesy of Jamie North, Sarah Cottier Gallery, Sydney.

Kyoko Hashimoto and Guy Keulemans, Large Prayer Beads (Daijuzu) (detail), 2018, concrete, steel rebar, 75 mm diameter x 6000 mm. Photo: Kyoto Hashimoto.

Smart Design Studio, Indigo Slam, 2016, Chippendale, New South Wales. Photo: Sharrin Rees.

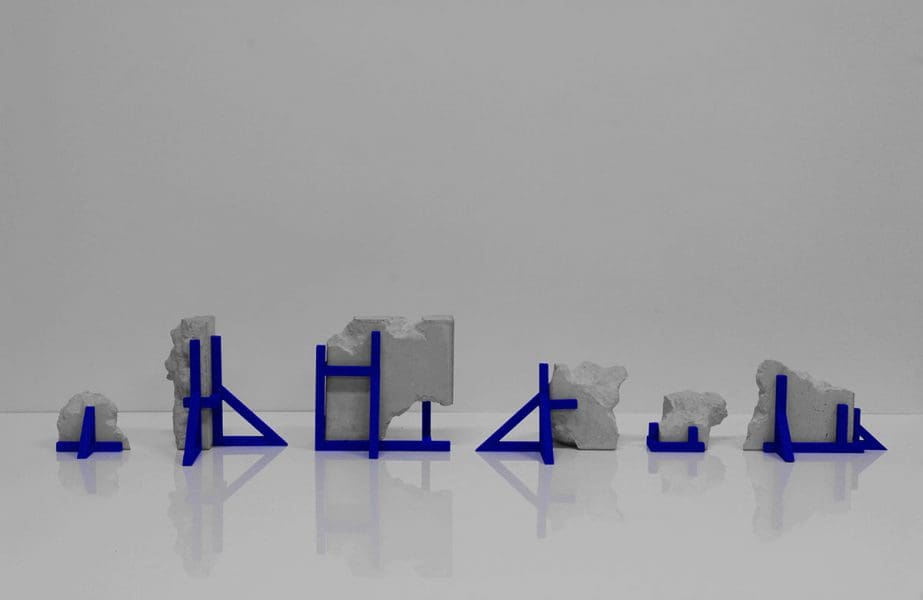

Tom Borgas, Concrete Topology (12 maquettes), 2018, concrete, wood, acrylic paint. 12 Fragments (dimensions variable – fragments taken from 144 x 144 x 144 mm concrete cubes). Installation: 144 x 1895 x 150 mm. Photo: Tom Borgas.

When architect William Smart was designing Indigo Slam, the iconic contemporary home of Sydney philanthropist and art collector Judith Neilson, he was at the site almost every morning. Arriving at 7am in running shorts, accompanied by his canine pal, he would oversee the creation of the structure’s impeccable, poetic, flowing form. Smart, who is enamoured with the sculptural qualities of concrete, is one of many creatives displaying his penchant for the material in CONCRETE: art design architecture.

Initially showing at JamFactory in 2019, and currently touring Australia, CONCRETE brings together 21 projects by artists, architects and designers to explore the conceptual, expressive and material qualities of concrete. Including sculpture, design, installation and architecture, the show lies within JamFactory’s art design architecture series that traverses four modern materials. “One of the things we aimed to do with the series is to show the many innovative processes and range of ways that materials are being used,” says lead curator Margaret Hancock Davis.

Used by the ancient Egyptians and Romans, concrete resurfaced as a major material in the 1800s before finding its stride in art contexts in the 1960s. While this history shows how elemental the material is, the exhibition is also concerned with narratives created through concrete, evidenced by artist Abdul-Rahman Abdullah. Known for his sculptural intricacy, Abdullah has taken influence from Rodin’s Man with the Broken Nose, 1863-1864, to sculpt his brother-in-law: a boxer who spent 25 years in the ring. Conjuring stories of familial bonds and expressions of masculinity, Abdullah’s creation alludes to the shape-shifting dimension of concrete.

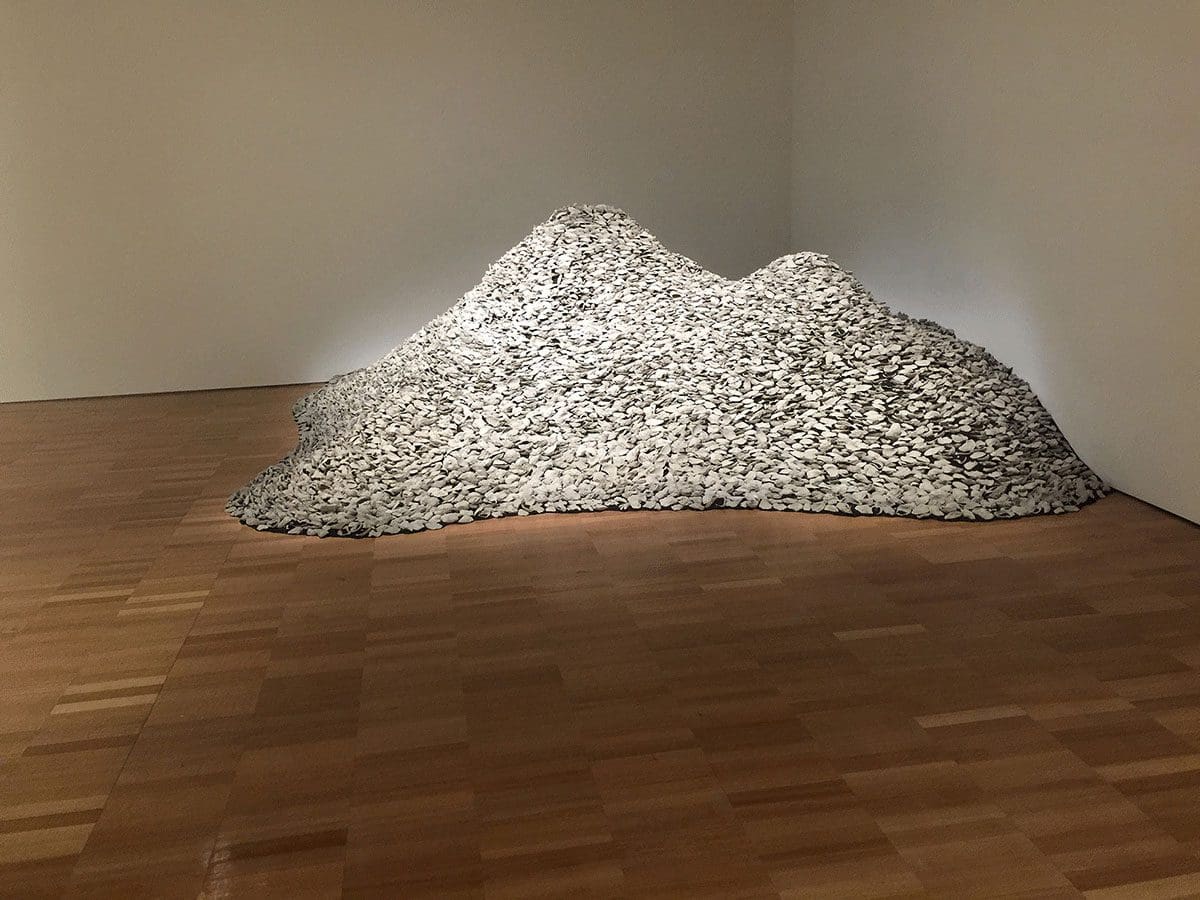

Within this thread of cultural concerns and material production also lies the work of artist Megan Cope. In a series titled RE FORMATION, the artist uses concrete to gesture towards reconstructing desecrated Aboriginal shell middens, which were stripped by early colonisers for mining. Meanwhile, designers Alexander Lotersztain and Adam Goodrum point to concrete’s cultural and public resonance by creating outdoor seating objects, exploring the relationship between functionality and beauty in shared spaces.

By evoking concrete as a non-static surface, the show’s architecture and design-based works highlight how environments and materials continuously impact one another. “What came out of conversations with the architects, as well as designers, was concrete being this palette that actually allows a surface to be an area that’s like a projected moving image,” says Davis. “They consider how, for example, concrete reacts throughout the day to light, shadow and clouds moving across the sky.”

Yet the narrative surrounding concrete is not always utopian; think environmental hazards and increasing development. And the exhibition engages with rather oblique pitfalls. For instance, the show includes work by Kyoko Hashimoto and Guy Keulemans which is grounded in how many modern buildings are produced from concrete reinforced by steel. While pure concrete buildings (such as the Pantheon in Rome) only strengthen over time, reinforced concrete is susceptible to rusting and cracking, leading to concrete cancer. The life-span of reinforced concrete buildings sits at a mere 100 years. Hashimoto and Keulemans reference this fragility by creating a large prayer bead of concrete and steel, which over time will crack and fall apart.

While such a perpetual interweaving of material and conceptual poeticism is always at the forefront in CONCRETE, the exhibition is not simply a display of diverging ideas and methods. Instead, as Davis explains, viewers are persuaded to notice the similarities and empathies which various artists approach, understand and use in concrete.

CONCRETE: art design architecture

Design Tasmania

1 July – 5 September 2021

An earlier version of this article was published by Art Guide Australia online in 2019.