Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

For Megan Evans, the past isn’t the province of history books. It’s the sum of complicated forces that shape the present day. For the last three decades, the artist—whose ancestors were from Scotland and Ireland, and who was married to the late Indigenous artist and activist Les Griggs—has made images, installations and sculpture that reflect on her role as the descendent of colonisers. PARLOUR, which won the 2019 Footscray Art Prize, shows viewers how power is upheld in domestic spaces and benign signifiers. Elsewhere, her ongoing Keloid project—referencing the term for a scar that grows beyond the original wound—challenges the privileges enshrined by whiteness while untangling the complexities of living on stolen land. “I’m interested in how one takes personal responsibility for these things,” says Evans. Here, she shares the stories behind five of her most compelling works.

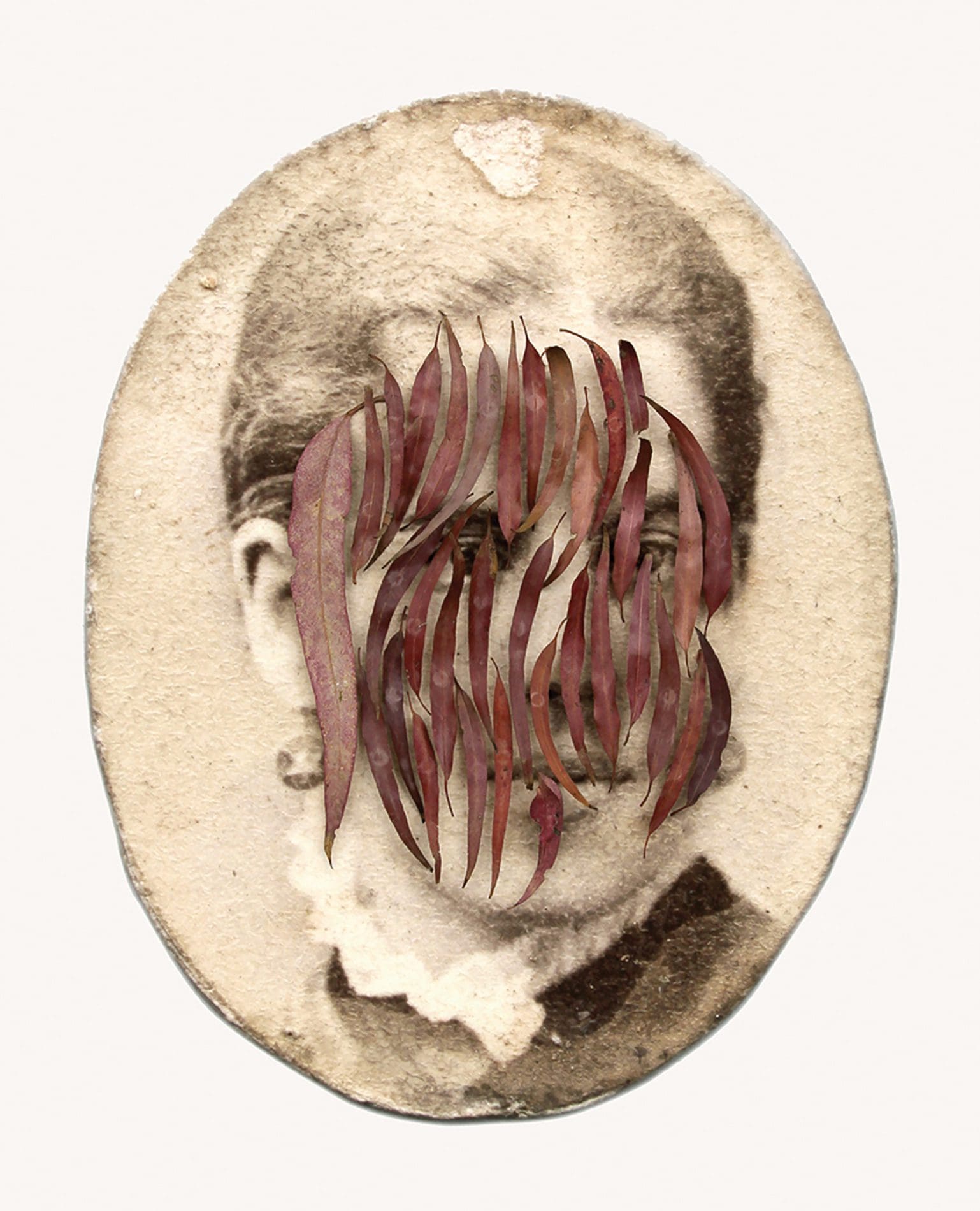

Megan Evans: Isabella Kelly was my great-grandmother. She was born in 1860 in Melbourne and this image is from one of her lockets. She married Patrick John Kelly. Her father came to Australia with his father, my greatgreat- grandfather, from Scotland. Isabella and Patrick were my first [ancestors] who were born here. They occupied land and I think if you were there at that time, you were complicit in what happened.

This was part of the first body of work I did for the Keloid project. I was dealing with extreme feelings of shame. I always distinguish between shame and guilt—I think guilt is negative. It works to suppress people who have already been oppressed. Isabella is peering out into the present but also hiding. The eucalyptus leaves are stuck onto pins, and the pins are stuck into her face.

Megan Evans: I’ve done a lot of performance and video work in a dress I had made based on one worn by Isabella. We talk a lot about the men that went out and conducted the massacres—but while that was going on, the women were sitting at home, doing embroidery, supposedly as part of a very civilised lifestyle. They may not have shot anybody, but they were also implicated.

I always remember my mum meeting Isabella at the station in Sydney, because she lived on this big property in northwest New South Wales. She didn’t want to carry a hatbox—she wanted to carry her hats on her head. She was eccentric. There is something about that that prompted me to put a silver cloche, used to cover food, on my head.

Megan Evans: The red in my work is quite painful. My brother died of a heroin overdose and after he died, I used to tie a red ribboned scarf around my head. People always asked, “Why do you always wear that?” and I realised that it was the tourniquet he used. Years later, I started doing paintings that had red ribbons in them. I started seeing them as bloodlines, as connections to my ancestry—almost like veins.

I look at objects as a kind of witness. People from the colonial era sat on those chairs and used that cutlery. Although the objects weren’t active they were part of the support structure of colonial violence. This exhibition, Squatters and Savages, was a collaborative project with artist Peter Waples-Crowe. Peter is Ngarigo and his Country is next to where my great-grandfather first occupied land. It was very real for both of us.

Megan Evans: PARLOUR is a replication of the Lindsay Family Parlour at the Art Gallery of Ballarat. I took out most of the Lindsay family’s furniture and put in my furniture and photographs. It was about transforming that space to present evidence of what was going on at the time.

Maree Clarke is wearing a Kopi mourning cap which is a traditional mourning practice from her culture. When someone died, they would cover their heads in white clay and the cap could sometimes be up to seven kilos in weight. The mourner would wear it until it disintegrated. Maree does Kopi healing workshops and when my mother died, she said, “I think you need to do a Kopi.” The clay covers your ears and when you have it on, it feels like you are protected from the outside world. When you lift it off, it is like you are lifting off the weight of the grief. It is an incredible thing.

Megan Evans: I’ve been collecting Victorian objects for a long time. The books in this photograph are Victorian Statutes from the 1800s and, like dictionaries, they go from A to Z. But this one is R to W and is titled Rabbit Suppression to Wrongs.

Some of these Statutes include text about the surveying of land and the division of districts. Some of them relate directly to Gunditjmara land which was my husband’s Country. It makes you realise how brutal and insensitive the carving up of land was. One of the gloves features the word kurrk, which is the Wathawurrung word for blood. I got permission from an Elder to use that word. My work is both beautiful and brutal. I’m always interested in how art can seduce people and whack them on the head at the same time.

UNstable — Keloid #8

Megan Evans

Horsham Regional Gallery

1 December 2020—28 February

This article was originally published in the January/February 2021 print edition of Art Guide Australia.