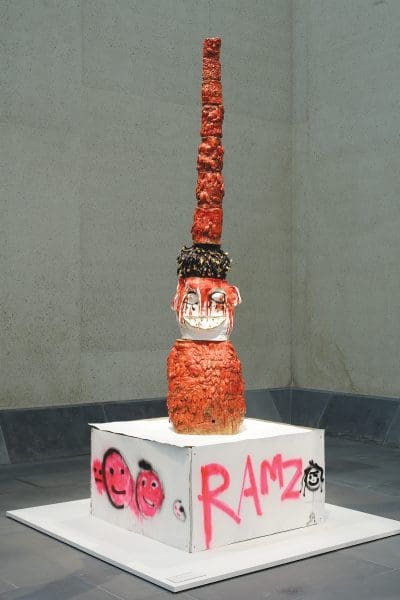

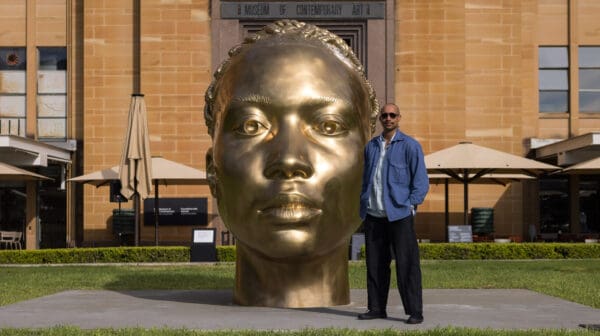

Monumental Disruption with Thomas J Price

Positioned on the edge of Sydney Harbour/Warrane, Ancient Feelings, a sculpture by British artist Thomas J Price, launches the Neil Balnaves Tallawoladah Lawn Commission, a three-year series of public artworks presented by the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia.