Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

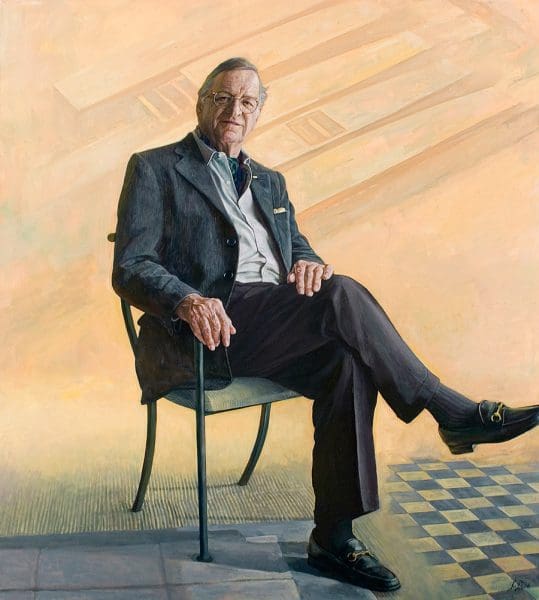

Visual arts may have supporters who contributed more money but Gordon Darling was our most important, long-term and passionate advocate.

He was strategic about how to direct funding, recruit other supporters and pursue a multifaceted program at all levels to enrich visual arts culture, all while gifting significant funds and works of art to institutions all over Australia, south-east Asia and Europe.

Darling died aged 94 on the 31st of August last year, having spent forty of what he once described as his most rewarding years in the art business.

His involvement in the arts had an almost accidental inception. Failing hearing caused him to withdraw from high-level business roles in 1986. He had held a seat on the board of BHP for some 32 years, while also serving as chair of Rheem Australia. His second career was the art business, and he approached it as seriously as he did his previous work.

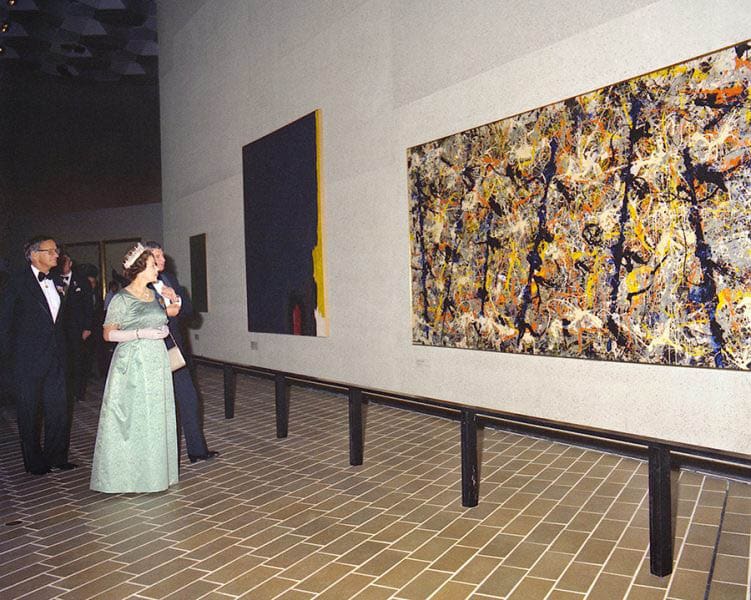

Darling’s major contribution to the arts is widely seen as being the establishment of Australia’s National Portrait Gallery, a labour of love inspired by his admiration for and enjoyment of such galleries in Washington and London. It opened in Canberra in 1994 and moved to its purpose-built home in 2008. As Australia’s newest national institution, the gallery has changed the dynamics of the arts in this country.

Darling’s most significant achievement and ongoing legacy, however, is arguably the Gordon Darling Foundation. Created in 1991, the body provides small but highly significant grants in support of regional galleries, publications, exhibitions and, most importantly perhaps, to assist museum professionals to travel.

“It is not a rich foundation,” says Phillip Bacon, who became a GDF Trustee in 2000, “but it offers funding where the need is great, in neglected areas.

“One of the most valuable things we do is to fund domestic and international travel – and Gordon really understood those benefits. The trustees agreed that the ability to visit other institutions, other exhibitions, to meet colleagues and participate in seminars and master classes was one of the most valuable tools we could give to regional and state gallery staff.”

Galleries in remote areas and far from the major cities’ flagship institutions are among the most important in terms of engaging people culturally, yet generally do not have a high profile. Darling’s support for these unsung bodies were a result of his own visits to the regions. “He was very plugged in, always,” Bacon says. “When he was on the board of BHP he travelled in the regions a lot, to mines and factories.”

Amongst his other achievements were the establishment and endowment of the Gordon Darling Australia Pacific Print Fund in 1989, which has, to date, acquired 7,000 prints for the National Gallery of Australia. Darling also initiated the establishment of the American Friends of the National Gallery association, an entity that allows for American citizens to donate to the Australian national collection.

“Gordon and James Mollison worked their magic to gain tax exemption in the U.S.,” Bacon says, “an almost unheard of achievement when up against the feared Internal Revenue Service, who wanted no truck with what they saw as a tax dodge to benefit some hazy institution Down Under.”

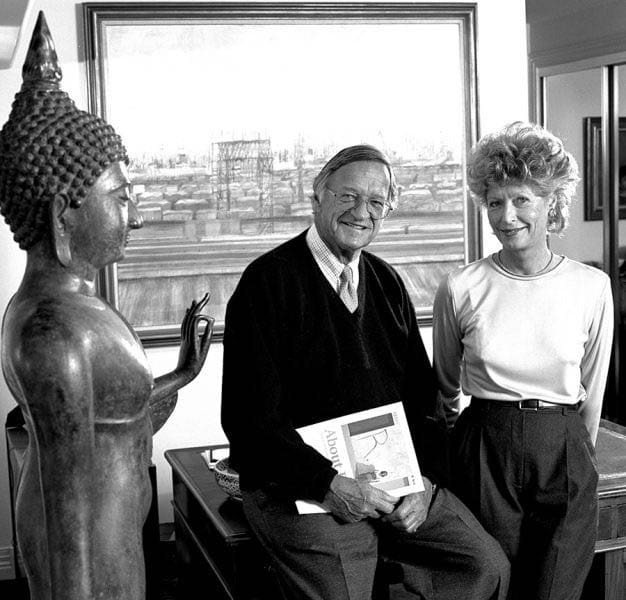

A tangible legacy of Darling’s contribution is the donated series of Albert Namatjira watercolours that hang in a dedicated room at the NGA, where Gordon served as its first chair from 1982 to 1986. The room, known as the Gordon and Marilyn Darling Gallery – Hermannsburg School, is now one of the most visited rooms in the gallery.

“While he knew all of the great leaders and politicians, sportspeople and celebrities,” Bacon said in a eulogy, “he was the least pretentious person you would ever meet. Art for Gordon really did matter. He believed in its importance to instruct, to enlighten, to entertain. He believed in its value to artists, particularly indigenous artists, and was a major collector more, I suspect, out of a desire to help the communities than to simply own the work.”