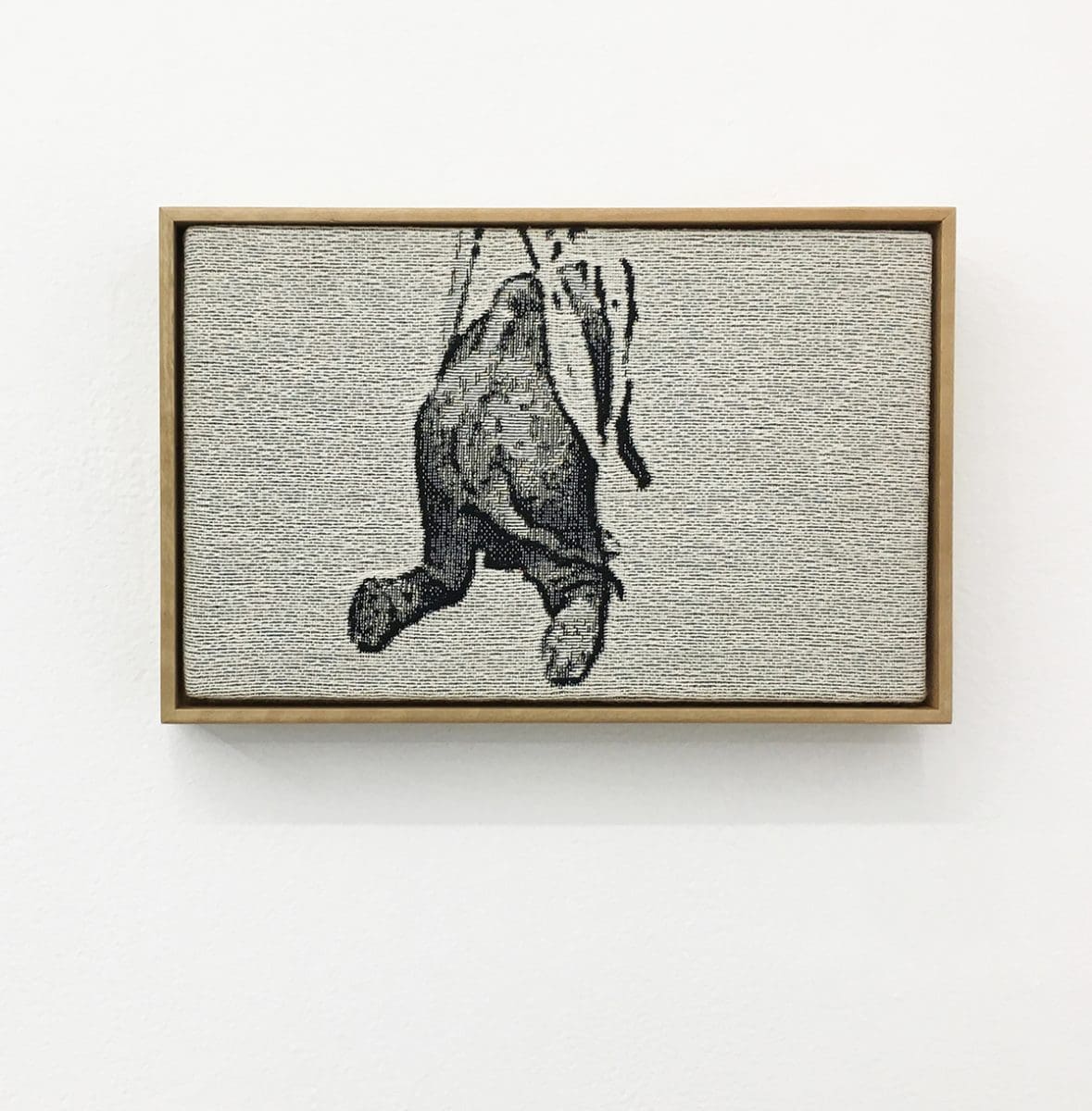

Suddenly Mansfield’s message became clearer. The artist presented three small monochromatic tapestries, each one based on a photo in which animals (a dog, an elephant, and a trio of cows) were suspended from harnesses. Sans titles, interpreting these images was simple. They evoked the seemingly endless capacity humans have for cruelty to animals, and, by extension, to other humans. (After all, we are just animals that can count a facility for technology, viciousness and self-destruction among our many and varied talents.)

In fact, The Last Vestiges of Instinct was all about the human animal and our impact on other critters.

Diminutive fetishes of goats, horses and bears lined the gallery walls. Roughly cast in white metal from children’s plastic toys, many of these little animals were missing limbs and loosely daubed with paint. While the amputations might be evidence of flaws in the casting process, some bore the scars of more deliberate human violence, both literal and metaphorical.

The small goat perched on a shelf in A saccharine undercut (a shrink and shudder at the guise of view), 2017, was subjected to the grinding wheel. Its body had been abraded away to reveal a swathe of metal; smooth and shiny like a wound that won’t heal.

Elsewhere a tiny metal polar bear balanced on a precariously thin metal outcrop. Positioned between the wall and a perilous plunge to the floor it could neither move forward nor back. It was utterly trapped, hopelessly doomed. Forget the titles. Left to their own devices Deb Mansfield’s works speak eloquently.

Deb Mansfield: The Last Vestiges of Instinct was at Galerie pompom, Sydney from 30 August to 24 September.