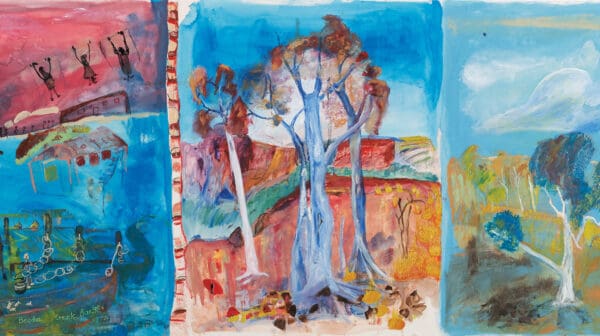

Creativity beyond mortality

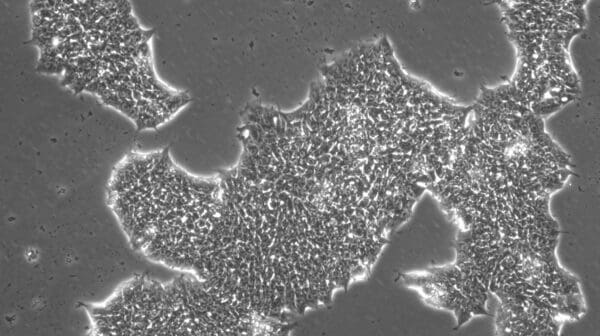

Have you ever wondered if someone who is no longer alive could create art? In answer to this question, biological artists Guy Ben-Ary, Nathan Thompson and Matt Ringold, in collaboration with the now deceased Alvin Lucier, have extended the experimental composer’s “ideas about the resonance of sound” for their immersive exhibition, Revivification at the Art Gallery of Western Australia.