Cars possess a mythical status in Madeline Purdie’s life. Purdie, an acclaimed Gija artist, lives in Warmun, a township between Broome and Kununurra in the Kimberley, a part of Western Australia known for a near-infinite sense of space and the ethereal curves of the Bungle Bungles. Her mother, the senior Gija artist Shirley Purdie, used to walk the expanse of Country to visit members of her community. When her family acquired a vehicle, everything changed.

“Mum’s paintings reflect how she grew up on a cattle station [Mable Downs] and had to work at a really young age,” says Purdie. “My mum and Aunty Mary grew up on the station. It would take them two to three weeks to get to their destination but when they had a car it only took them two hours. She used to sit in the back as her dad’s brother took them visiting family in Texas Downs, Bedford Downs.” She dissolves into laughter. “She told me that she thought that the car came down from heaven. That God gave them the car.”

“Tos Mahoney, the artistic director of Tura New Music says that Warnarral Ngoorrngoorrool, the Gija word for ‘old car’, has roots in Wreck.”

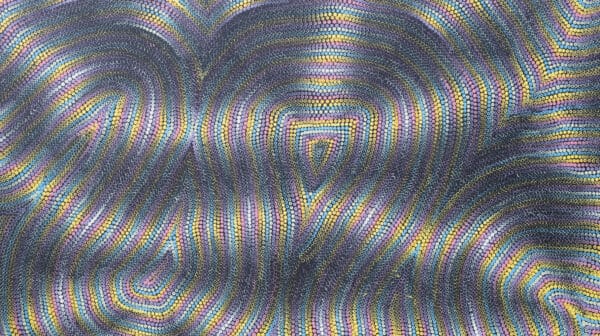

The Purdie family car, an old Dodge, is the subject of a painting by Shirley Purdie. Alongside works by artists such as Gordon Barney, Nancy Nodea, Lindsay Malay and Charlene Carrington, Purdie’s piece has been painted on an unlikely canvas: the surface of a 1975 Mazda ute. It was once owned within the Purdie family, then abandoned in the bush on Gija Country. Throughout July, this painted car will embark on a 3,200-kilometre trek from Kununurra to Perth’s WA Museum Boola Bardip, where it will be exhibited.

It will stop everywhere from Fitzroy Crossing and Broome, to Roebourne and Geraldton, as part of a project by Tura New Music called Warnarral Ngoorrngoorrool: The Journey Down.

Tos Mahoney, the artistic director of Tura New Music says that Warnarral Ngoorrngoorrool, the Gija word for ‘old car’, has roots in Wreck. This previous work, conceived by Jon Rose for the 2013 Sydney Festival, saw the renowned composer turn a dilapidated car from a New South Wales mining town into a musical instrument.

“Fence wires were stretched from the front to the back of the car which brings this element of percussion,” Mahoney says. “It gets picked up and amplified and makes this amazing wall of sound with many possibilities.”

The concept of turning an old car into an instrument, says Mahoney, resonated with Western Australia’s Gija and Miriwoong communities, for whom the car symbolises distance and displacement, but also tells a wider story about culture and connection. In 2017, Rose, as part of a regional residency with Tura New Music, collaborated with Warmun artists, musicians and students to create another iteration of Wreck, inviting participants to both paint and perform with the touring car. While Rose created the car-as-sound sculpture with the Warmun community, the sounds and performances involving the car will be produced by the Warmun artists.

“I knew that there was a lot of story surrounding car wrecks on Country that make these amazing sculptural—and cultural—objects,” says Mahoney. “Through the Warmun Art Centre we commissioned stories to be painted [on the car]. You’ve got Gabriel Nodea’s story which is the Warmun creation story about the eagle and the crow. Gordon Barney’s is a massacre story which is very bleak. Charlene Carrington’s is a modern parable—she does a lot of health work and she did this painting of a tree whose seeds fall out.” He pauses. “There’s this juxtaposition with Jon’s postmodern deconstruction. It’s a very beautiful thing.”

Warnarral Ngoorrngoorrool is a vehicle for Gija culture. But Mahoney wants the touring vehicle, which will feature performances by Gija and Miriwoong artists, to echo the spontaneity and inventiveness that unfold on Country. “Jon has written a manual on how [the car] can be played but we don’t want to overdefine it,” he says. “There are projections, animations of the painting, Gija songs and stories. We wanted Warnarral Ngoorrngoorrool to reflect what happens when song and story and dance happen in community. It has its own rules but varies.”

“Madeline Purdie is excited about what Warnarral Ngoorrngoorrool means for her community. “They are taking the car down to Perth, through a lot of Country and even getting our mob who will be travelling with it, speaking and dancing,” she enthuses.”

Tura New Music has spent close to two decades fostering relationships with Gija and Miriwoong communities. Warnarral Ngoorrngoorrool, he says, is the result of intercultural collaboration and a commitment to long-term cultural exchange.

“It is part of an ongoing collaboration that involves various local people and artists and non-local people and artists, and it’s all been done observing protocols in good faith,” he says. “There’s this idea of the colonial object that is dumped into the bush and decomposes— that statement, in itself, is powerful. But there is this mythologising of First Nations cultures which Australia is getting guiltier of doing. There’s the idea of story equalling myth. But, equally, there’s also the story of the everyday. Of the car that ran out [of town] and is now over there.”

Madeline Purdie is excited about what Warnarral Ngoorrngoorrool means for her community. “They are taking the car down to Perth, through a lot of Country and even getting our mob who will be travelling with it, speaking and dancing,” she enthuses.

To Purdie, the car doesn’t just connect people and places. It’s also a bridge between past and present. “I use a car to go to work, to visit my clients who are elderly, to visit family,” she smiles. “If you go to healing camp, you have to drive. Sometimes we have to make our own roads. The car is such a powerful thing for my generation.”

Warnarral Ngoorrngoorrool: The Journey Down

Various touring locations, with final exhibition at WA Museum Boola Bardip

24 August—17 September

This article was originally published in the July/August 2023 print edition of Art Guide Australia.