Jennifer Kemarre Martiniello’s Glass Acts

Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards 2025 finalist Jennifer Kemarre Martiniello has spent decades crafting an art practice that weaves together memory, heritage and form.

Casino Wake Up Time. Photograph: Kate Holmes. Image commissioned by Arts Northern Rivers for the Bundjalung weaving publication project 2021, supported by the Office for the Arts.

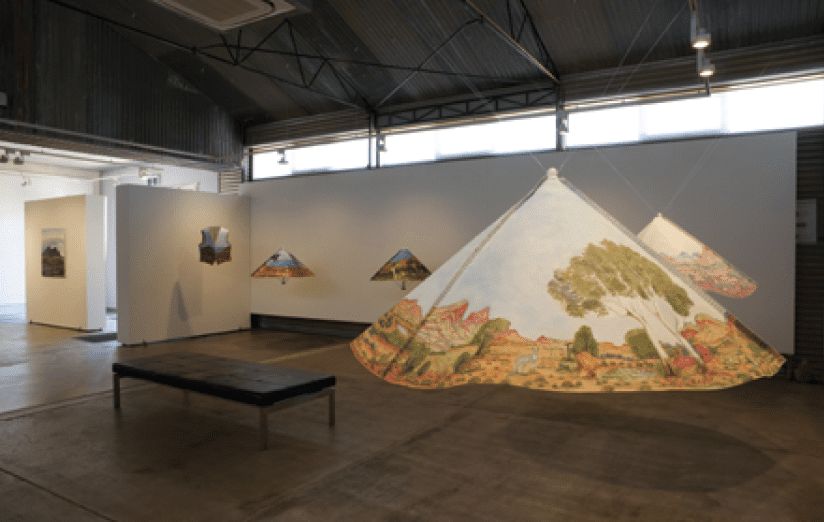

Selma Coulthard, Urrampinyi (Tempe Downs), West of Alice Springs, NT, 2021. Installation view of Kutja Malla Manttara – Collecting (Bush foods) in cloths, 2021, RAFT Art Space, Alice Springs. Courtesy the artist and Raft Art Space. Photograph: Martina Capurso.

Mata Aho Collective, Kiko Moana, 2017. Installation view for documenta 14 at the Museum of Hessian History (2017), Kassel, Germany. Courtesy the National Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington. Copyright © Mata Aho Collective.

Biennales have often upheld the idea of the artist as a singular genius. But for Hannah Donnelly, artistic practice isn’t just about individual talent. It’s a consequence of connections between people and intergenerational knowledge that’s nurtured and passed down.

Donnelly, a Wiradjuri curator, writer and producer, is part of the curatorium for the 23rd Biennale of Sydney, championing the work of groups such as Iltja Ntjarra (Many Hands) Art Centre, Casino Wake Up Time and New Zealand’s Mata Aho Collective. But a collective ethos, she says, doesn’t just define the artists presenting work at the Biennale. It shapes the curatorial vision itself.

“It’s really exciting, seeing the rise of collectives, co-artistic directors and curatorial models,” she smiles. “For me, working with collectives and working on First Nations land is about things that are actually good practice—consensus decision-making, the principles of free, informed and prior consent. It means having more conversations and being accountable to [more people].” She pauses. “How we define a work of art isn’t just about one person. It’s about everything around it too.”

A moment shaped by climate crisis, a global pandemic and the failures of neoliberal capitalism calls for a different kind of art world—one that is inclusive, generous and imaginative. This Biennale refers to artists as “participants”, challenging Western hierarchies of art and craft. Titled rīvus, Latin for ‘stream’, it also gives voice to Sydney Harbour, rivers and waterways. These bodies of water, according to Indigenous thinking, aren’t passive elements of the landscape. They’re living, breathing beings. Donnelly says that rīvus imagines itself as a series of ‘conceptual wetlands’, a metaphor that speaks to ideas of ecology, collectivity and co-existence.

“In Sydney, we have this beautiful saltwater story in the Harbour and [a place] where saltwater meets freshwater in Parramatta,” says Donnelly, who is working with Dharug custodians and communities such as the Friends of Myall Creek. “But water is often dark and full of sad stories. A lot of the First Nations artists [draw on] ancestral knowledge of water, water as a site of conflict. There is a lot of work [that] looks at healing as well.

Mata Aho Collective

Sarah Hudson believes that art-making doesn’t have to be an isolated endeavour. It can be a collaborative expression that’s more than the sum of its parts. In 2011, Hudson, a Ngāti Awa, Ngāi Tūhoe and Ngāti Pūkeko artist, met Erena Baker, Bridget Reweti and Terri Te Tau—Māori women artists who shared her sensibilities. The four women, based in Aotearoa New Zealand, have been making work as Mata Aho Collective ever since, becoming known for their large-scale works. “We had read the same books, made work about similar things,” says Hudson. “We found great strength from being together in the art world, having friends by your side while trying to figure things out.”

Aho is the Māori word for weft. Sewing, an artform that connects disparate elements, is central to Mata Aho. At documenta14, which took place in Kassel, Germany, the group showed Kiko Moana, 2017. The deep blue installation, woven out of tarpaulin, reflects their ongoing commitment to everyday materials and evokes taniwha—creatures that hide in oceans, rivers and caves.

It speaks to their fascination with Māori deities as well as the knowledge carried by women’s bodies, a guiding tenet of their work. “There’s a goddess that looks after freshwater systems, Parawhenuamea, and a [goddess] Hinemoana that [looks after] the open sea,” says Hudson. “And then there’s a point where the rivers meet the harbours and those waters exchange.”

This union of freshwater and saltwater is central to He Toka Tū Moana (She’s A Rock), a woven installation that will wrap around the columns of Barangaroo’s The Cutaway as part of the Sydney Biennale. “There’s a Māori proverb that talks about a rock in the ocean and the strength it has to stand up to these moving waters,” Hudson says. “We did some research into Barangaroo and we see her as a cultural beacon, a strong rock.”

For Te Tau, Mata Aho’s evocation of Māori mythology isn’t just about upholding tradition. It’s about a sense of kinship with the natural world that can draw the viewer into a spirit of care and reciprocity. “We can trace our genealogy to these personified beings, so it creates the same responsibility as a family relationship,” says Te Tau. “If you are thinking of the [natural world] in terms of family, you are not going to be extracting. You are thinking in terms of giving back.”

Casino Wake Up Time

Weaving is communal, a chance for women to find community. For Kylie Caldwell, it’s also a form of renewal, a way to make traditions she was searching for part of everyday life. Six years ago, Caldwell started working with Casino Wake Up Time—a collective largely based in Casino that has been meeting for 10 years to share stories and craft. The collective, also comprising Theresa Bolt, Auntie Janelle Duncan and Auntie Margaret Torrens, would gather plants native to Bundjalung Country (the northern coastal area of New South Wales) before spinning them into jewellery, bags and baskets. She describes becoming part of the group as a “gift”.

“I lost my grandmother when I was six and never met my grandfather,” she says. “If you grow up in the Western world, [culture] is hard to find. Since I’ve had my children, I’ve not had the chance to gather with women, have yarns, talk about stuff. Our old women did that—they used to weave together, collect together and the children would follow.”

Bundjalung Country is subtropical, a climate that lends itself to plants such as pandanus and buckie rush. “We weave with a buckie rush reed and then there is a beautiful native hibiscus which our string bags are made from,” she says. “We have a lot more wetlands because of progress and agriculture.”

Although the group’s members have presented pieces at workshops and markets, the Biennale marks their first collaboration. Caldwell says that the group was playing with the idea of waterbeds.

“But on the flipside, there is that song that goes, ‘How do you sleep when the beds are burning?’” she grins. “Our bodies are composed of water, the things we eat need water. We need to pay attention to water now.”

For the Biennale, the group’s weaving incorporates cast-iron bed frames, a motif that references traumas of colonisation—such as the dormitories associated with the Stolen Generation. “It’s about how that [removal] of culture interrupted weaving practices,” says Donnelly. Caldwell points out the connection between colonial violence and environmental damage. “It is about our homeland, where we sleep at night,” she says. “The connection to water is everything in our life.”

Iltja Ntjarra (Many Hands) Art Centre

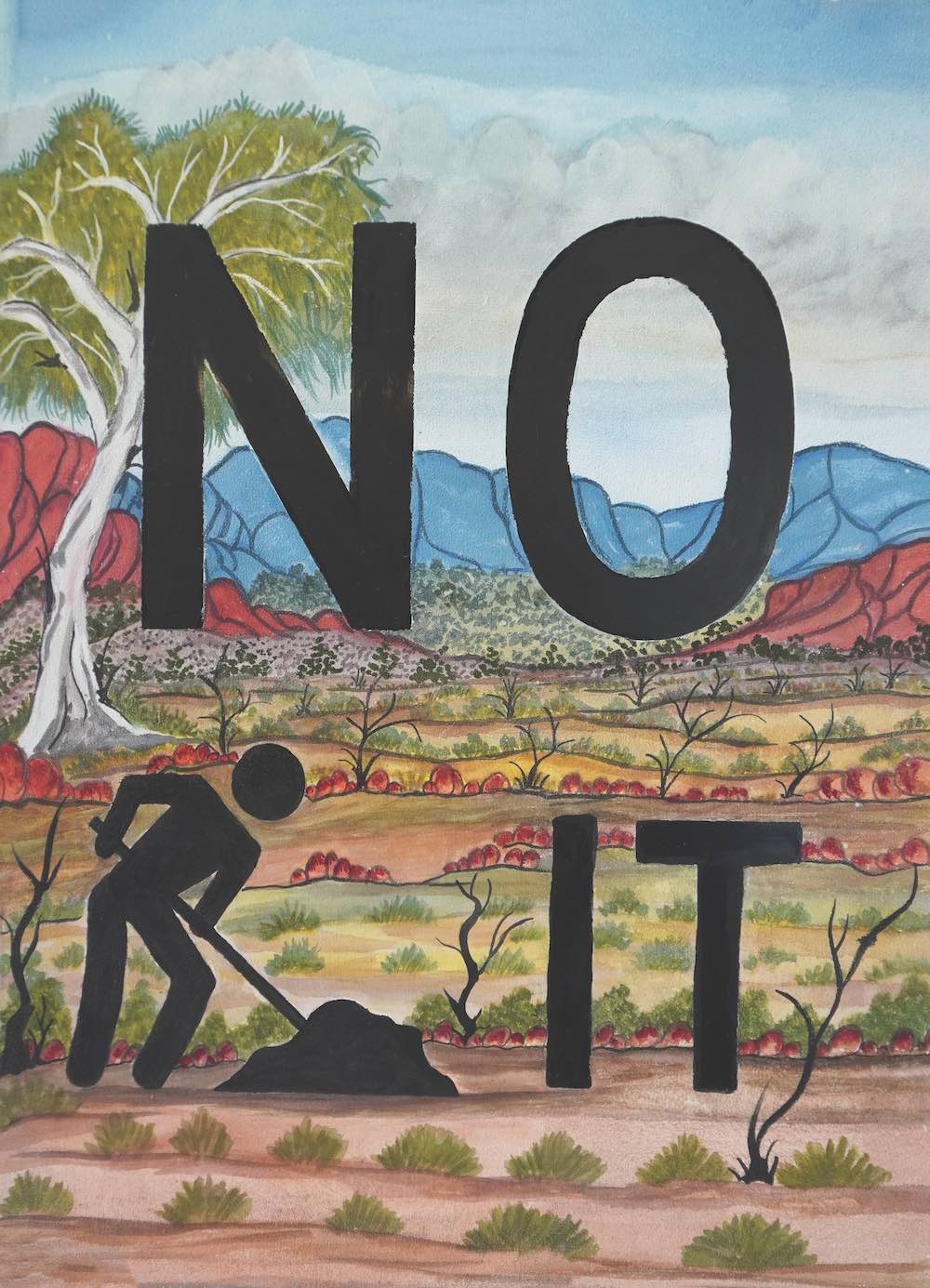

The great painter Albert Namatjira introduced the world to Western Arrernte Country: the intricate grooves of the MacDonnell Ranges, the purples and greens of the Central Desert. The Iltja Ntjarra (Many Hands) Art Centre has spent the last two decades preserving the watercolour traditions of the Hermannsburg School, the painting style Namatjira famously mastered at a Lutheran mission. The centre’s artists—whose members include Mervyn Rubuntja, Selma Coulthard and Kathy Inkamala—are dedicated to upholding their ancestor’s powerful visual legacy.

But Marisa Maher, a Western Arrernte woman and the centre’s assistant manager, says that they are equally dedicated to voicing contemporary concerns. For instance, the previous 2020 Sydney Biennale saw the artists present works such as Homeless on my homeland, 2019, and My homeland is being destroyed, 2019. The ethereal watercolour paintings and text, emblazoned on cheap, tartan, plastic laundry bags, spoke to displacement, dislocation and the disposability of land and culture. “Homeless on my homeland,” read the text on one bag. “This is something they [the centre’s artists] have experienced over the years, when they relocated to Alice Springs—trying to get their own place,” says Maher. “They want to express that through their painting, do something contemporary, show what they experience.”

Rīvus will see the artists reprise this wit and sense of material invention. Thirty works, featuring watercolour images and text painted on salvaged road signs, mount a protest against practices such as fracking, a threat to Indigenous water sources in remote parts of the country. “You can really see the words in the paintings,” says Maher who is co-curating the presentation. “[It’s] about caring for Country, protecting Country. I think they are all great.”

Casino Wake Up Time

Walsh Bay Arts Precinct

Mata Aho Collective

The Cutaway at Barangaroo

Iltja Ntjarra (Many Hands) Art Centre

The Cutaway at Barangaroo

12 March—13 June