We open and close on snow. A wide expanse of bone-white recedes into the horizon. It is the kind of snow—diaphanous, weightless, suspended in mid-air—that might be mistaken for magic, were it not for its frigid clarity. Anyone who has felt a snowflake on their cheek knows its cool shock: a trance punctured by a truth.

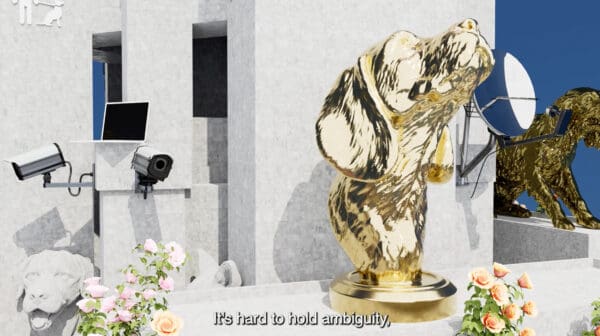

Trances and their antidotes: these are the forces which animate Isaac Julien’s Once Again… (Statues Never Die), the British artist’s 2022 video work now showing at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art. Over five looming screens, the film unfurls like a dream. We move between locations as if buoyed by a gust—frosted gardens giving way to labyrinthine museum collections and galleries heaving with gilded frames, soigné speakeasies and lovers’ bedrooms cast in a Vaseline-lensed fog.

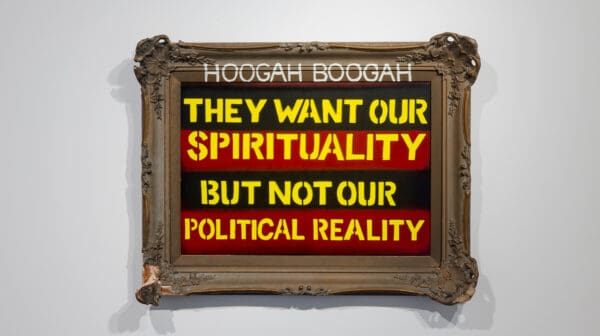

These spaces—plush and frequently palatial—are nothing short of reverie. Within them, though, Julien stages a far thornier discourse around art and its colonial injuries. He visits, again and again, an imagined dialectic between two cultural confrères and sometimes combatants: Alain Locke, the Black author who ignited the Harlem Renaissance of the early 1900s, and Albert Barnes, the rapacious collector whose gallery—Philadelphia’s Barnes Foundation—first commissioned this work to celebrate its centenary.

The men share a fascination with African art, though they diverge in their approach. In one declaration, Barnes (played here by Succession’s Danny Huston) vaunts his own “prophetic visions” in bringing the “statues of the African Black race” into public view. Locke (Moonlight and Passing’s André Holland) remains cautious. These African pieces, he warns, are the spoils of imperial avarice, purloined from their motherlands “first as curios then as prizes of comparative knowledge”. He poses a provocation: how might we begin to understand the work rather than exploit its “primitive charm”?

The film posits no answers. Julien’s practice, as always, is less philippic and more filigree. Like his 1989 breakout Looking for Langston, a revisionist elegy to poet Langston Hughes, or his 2019 work Lessons of the Hour, an elliptical portrait of abolitionist and freed slave Frederick Douglass, Once Again… sublimates its polemics beneath something more ornate and impressionistic.

Julien crafts a collage of references, each mourning the lingering wounds of the colonial project. There is archival footage from You Hide Me, a 1970 Ghanaian film urging the restitution of African works still entombed in the British Museum. There are lines from a British soldier’s diary narrating the 1897 Benin Expedition and its ensuing devastation. A curator character (Sharlene Whyte) wanders through aisles upon aisles of artefacts housed in Oxford’s Pitt Rivers Museum, arranged in rows so narrow they begin to blur. She recites an affecting Aimé Césaire verse: “Everything that has ever been torn apart / has been torn apart in me. / Everything that was ever mutilated / has been mutilated in me.”

The result is an imbricated lament to the sculptures wrested from home and hurtled across oceans to be ogled or overlooked—it isn’t clear which fate is worse. I’m reminded of Mati Diop’s recent Golden Bear winner Dahomey: an account of 26 royal sculptures returned to Benin after centuries in France. It is ostensibly a documentary, though that label seems too prosaic for Diop’s far eerier stylings. In various interludes, a repatriated wooden effigy soliloquises from its own perspective, grieving its “incarceration in the caverns of the civilised world”.

The artefacts in Julien’s film don’t speak, though he grants his characters a similar miracle. Locke—alongside his long-time confidante and occasional beau, the sculptor Richmond Barthé (Devon Terrell)—all but bounds through fantastical sequences inverting the gallery into a site of Black ecstasy. They observe a Black life model, taut and Adonic, who wields a gravitational pull in a studio of artists; they pace together through museum displays, barely able to contain their boyish glee.

And at last, Julien places them shoulder to shoulder on two adjacent screens, their tuxedos mottled by snowfall. “I’ve left time behind,” Locke avers in a voice-over, before quoting a bell hooks text: “In the mythical, diasporic dream space, a culture of infinite possibility is ready to receive us.” Then something remarkable happens. The snow begins floating upwards, gliding towards the firmament. We’re lulled into a dream. But unlike snow, this one doesn’t dissolve.

Isaac Julien: Once Again… (Statues Never Die)

Museum of Contemporary Art

On now—16 February 2025