Cartographies of the heart

Five Acts of Love, a new exhibition at ACCA, maps the space in which memory, intimacy and resistance intersect.

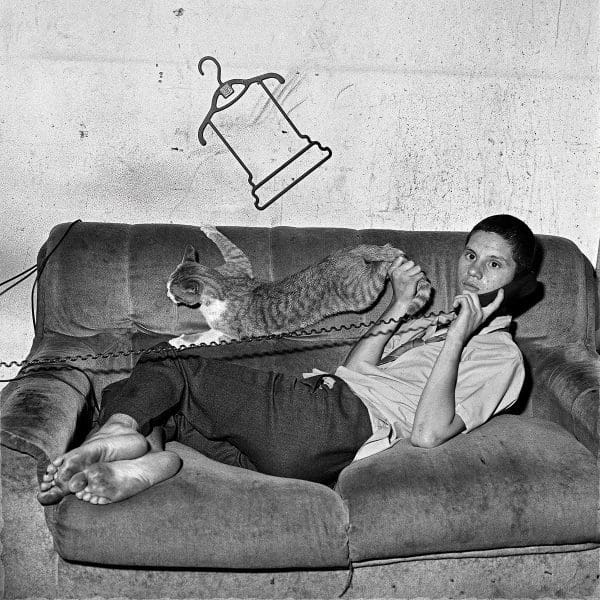

Roger Ballen, Eugene on the Phone, 2000, 40cm x 40cm, edition 32 of 35.

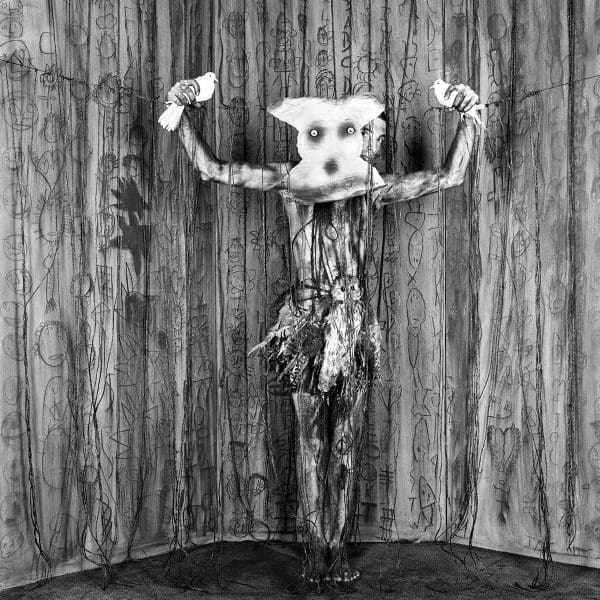

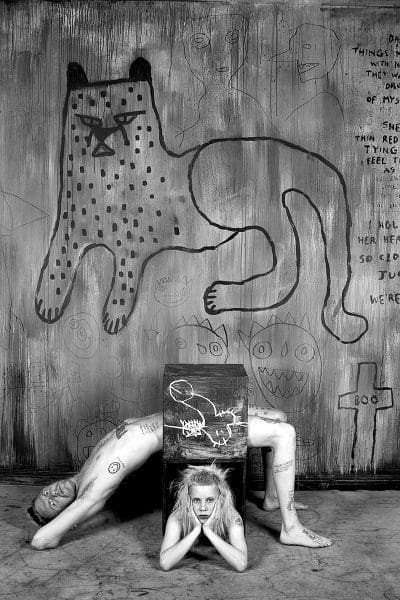

Roger Ballen, Alter Ego, 2010, 61cm x 61cm, edition 6 of 12.

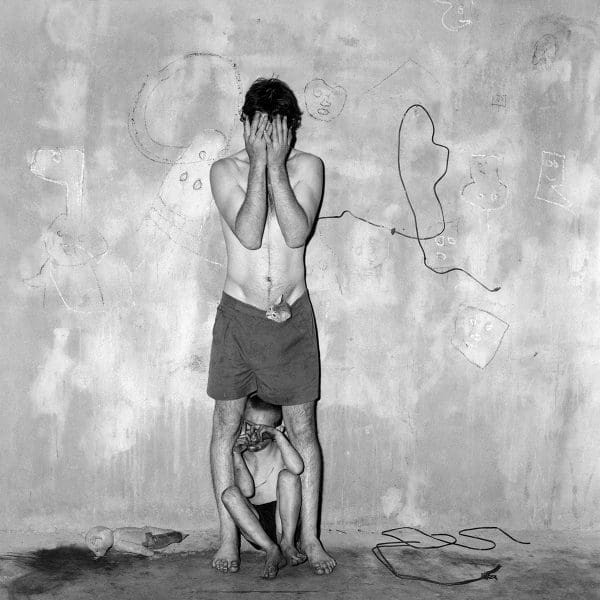

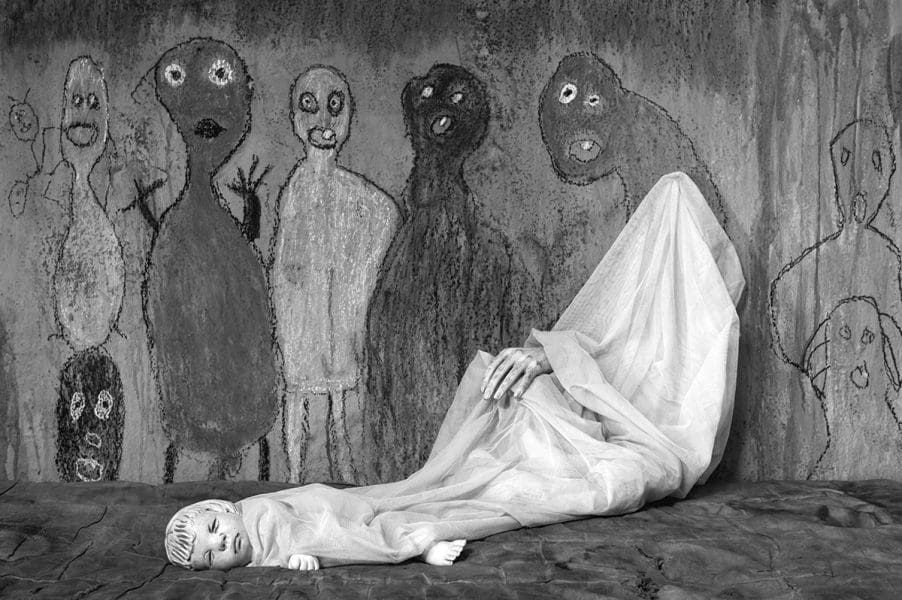

Roger Ballen, Concealed, 2003, 50cm x 50cm, edition 3 of 10.

Roger Ballen, Family man, 2016, 85cm x 61cm, edition 2 of 5.

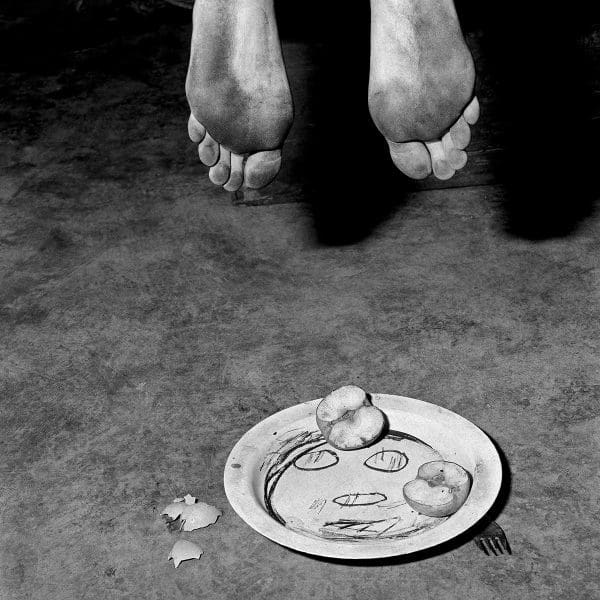

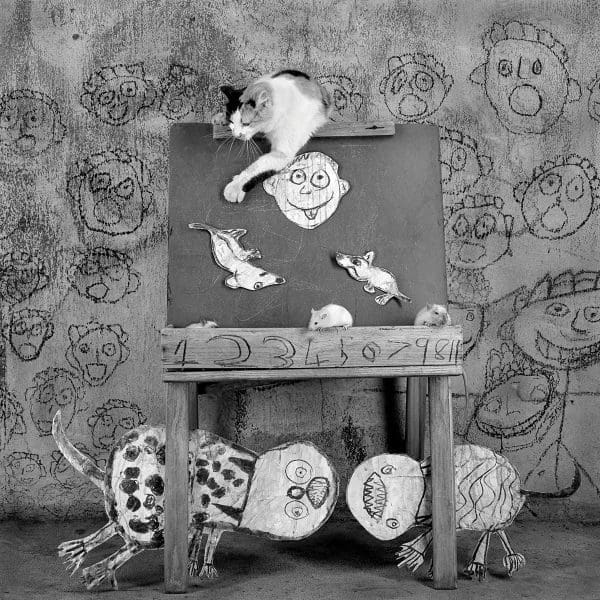

Roger Ballen, Fragments, 2005, 50cm x 50cm, edition 9 of 10.

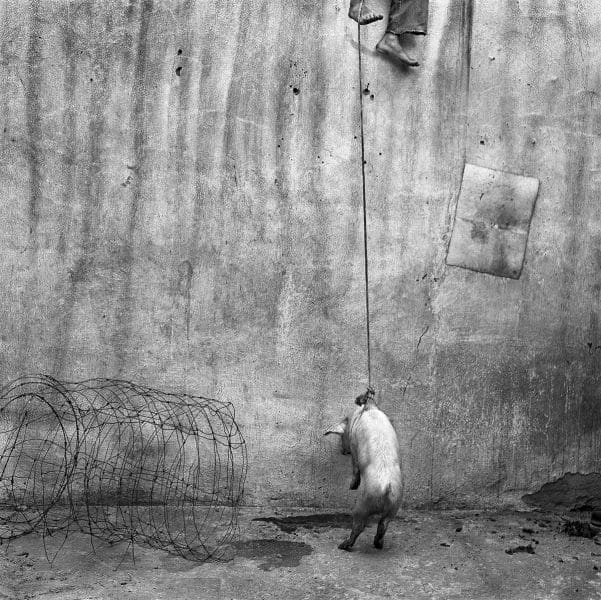

Roger Ballen, Hanging pig, 2001,40cm x 40cm, edition 31 of 35.

Roger Ballen, Pielie, 2012, 37cm x 35cm, edition 16 of 50.

Rats, rabbits and snakes surround skinny, angular, shirtless dancers, all rendered in black and white in a dark room whose filthy walls are daubed in drawings of aroused part-human, part-animal figures. The resulting images are seemingly scraped from the dank nightmares that the gentler conscious hours usually allow us to quickly forget.

New York-born, Johannesburg-based photo artist Roger Ballen calls this a “shadow world,” and this particular video collaboration with South African hip hop act Die Antwoord for their song I Fink You Freeky (2012) has been viewed 130 million times on YouTube. That familiarity hasn’t stopped Adelaide gallerist Paul Greenaway including the video in his new Ballen survey.

“It’s so good, isn’t it?” says Greenaway, who is showing I Fink You Freeky in the back gallery of GAGPROJECTS on a loop alternating with the documentary short Asylum of the Birds (2014), directed by Ben Crossman, which follows Ballen into a compound outside of Johannesburg that is shared by refugees, prison and asylum runaways, and birds and rodents. Also showing is the short film Ballenesque (2017) and, arguably the most confronting exploration of Ballen’s art in all its violence and milky-eyed human insanity, Outland (2015).

The main gallery will display works Greenaway chose from six Ballen series, dating from the year 2000 onwards. “I sent a list of the 33 works to him and thought, ‘Well, maybe he won’t send all of them; maybe he’ll want to edit it,” recalls Greenaway, who consciously avoided works shown at the Sydney Biennale and the Art Gallery of Western Australia in recent years. “Anyway, he didn’t. Straight away he said: ‘Fantastic selection; let’s do it.”

Ballen, 68, has been taking photos for more than half a century. He began work as a geologist and picked up a camera to document squatter camps and mine dumps in simple square portraits. “He speaks about his time as a geologist and the layering of things,” says Greenaway. “He wanted his photographs to go to the lower and darker depths.

“When he talks about shadows, if you look at the very early work, those long shadows were constantly there. I’m not saying anything against those early works, but it nearly became a device in all his early photographs. It looked like he was searching for the shadow before the subject.”

Beginning his career, Ballen travelled for five years on his own, compiling images that would come to form his first book. Hitchhiking from Cairo to Cape Town, from Istanbul to New Guinea, along the way he documented the end of traditional cultures.

“Maybe the subjects are not necessarily the subject of the work, in a sense,” says Greenaway. “The subjects are the notions of marginalised people or the environment that they’re in, rather than the people.”

Would Greenaway agree? “I think it’s sort of super-humanising. I wouldn’t agree with ‘dehumanising’ them at all. Often the subjects are really looking at you. There’s an engagement that’s quite unsettling. There’s a sense of alienation, and that’s something that comes from the spectator rather than [Ballen], because we’re the ones who want to have the safety of being the voyeur.”

Ballen – who couldn’t make it to Australia for the GAGPROJECTS show because he is engaged with another show opening in Montevideo, Uruguay – does not employ obvious politics in his art, argues Greenaway.

“The work itself doesn’t take a strong single position; he puts it out there and leaves it up to others. He’s not didactic; he’s not saying, ‘Look at these poor people; we need to do something’ in any way whatsoever. We know that he’s not part of the disenfranchised peoples of South Africa. He’s not preaching in any way.”

Despite obvious comparisons with the work of Diane Arbus, Ballen named absurdist Irish playwright Samuel Beckett – whose play Waiting for Godot famously has downtrodden characters waiting for someone that never comes – as an influence on his breakthrough collection of work, Platteland, (which is Afrikaans for country), published in 1994.

His image Dresie and Casie, twins, Western Transvaal (1993), a portrait of brothers with arresting features such as long heads and protruding ears, continues to attract almost obsessive public attention.

“It’s strange, isn’t it?” says Greenaway. “He’s said it really surprises him. Where the dead cat [image] is a pivotal one for him, the iconic work of his is not one he necessarily singled out as anything particularly more interesting than any of the others from that series.”

The New Yorker has said Ballen’s work combines hurt and hilarity. “It’s a very dark humour,” says Greenaway. “We all know that if you laugh or smile, your stomach muscles relax, and the knife goes in easier.”

Read Roger Ballen’s 2016 interview with Art Guide Australia here.

Roger Ballen

GAGPROJECTS | Greenaway Art Gallery

27 February—31 March