Material curiosities: Primavera 2025

In its 34th year, Primavera—the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia’s annual survey of Australian artists 35 and under—might be about to age out of itself, but with age it seems, comes wisdom and perspective.

Animal masks, headless budgies and reptile skeletons are frequent sights in the photography of contemporary Australian artists Polixeni Papapetrou and Petrina Hicks. While each artist favours elements of the performative in their work, stylistically they are opposites. Papapetrou’s images are resplendent with richly textured backdrops while Hicks submerges her subjects in luminescent white and sparse interiors. In the concurrent solo exhibitions Olympia and Bleached Gothic, the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) have highlighted significant portions of their work.

Throughout the two decades she practiced photography, Papapetrou, who passed away in 2018, produced images imbued with a darkly beguiling magic. Influenced by Diane Arbus, an American photographic artist known for her black and white portraits of people living on the outskirts of conservative 1960s society, Papapetrou spent her early days photographing circus performers, body builders and Elvis impersonators. Already well versed in staging and costumes, following the birth of her first child Papapetrou’s images became populated with more elaborate sets and costumes, fabricating fairytale, dreamlike environments. Increasingly, she began to include her young daughter in her portraits, and it is a selection of these images that we see in Olympia.

Curated by the NGV’s senior curator of photography, Susan van Wyk, the exhibition covers the time between Olympia’s birth in 1997 and Papapetrou’s death in 2018. Throughout Olympia, Papapetrou’s manipulation of painted sets and costumes morph into depictions of transitory states and the momentary slippage between reality and imagination. “For Poli, the sets allowed a richer exploration of stories and it also created a space for her models, who were children, to enact the stories,” says Van Wyk. “Being children, they were able to respond to the studio spaces, props and settings as though they were real.”

Discussing why she began to include children in her work, in a series of interviews conducted at her home studio in 2012 and 2013 Papapetrou revealed to curator and friend Natalie King, “When I gave birth to my daughter Olympia in 1997, a feeling of sadness swept over me because I understood that with birth comes death; birth and death are intertwined. It became important for me to photograph my children in a way that made their age and character elastic.” In doing so, Papapetrou created a vast visual documentation of the mystery, power and physical metamorphosis that takes place during the journey from childhood to adult life.

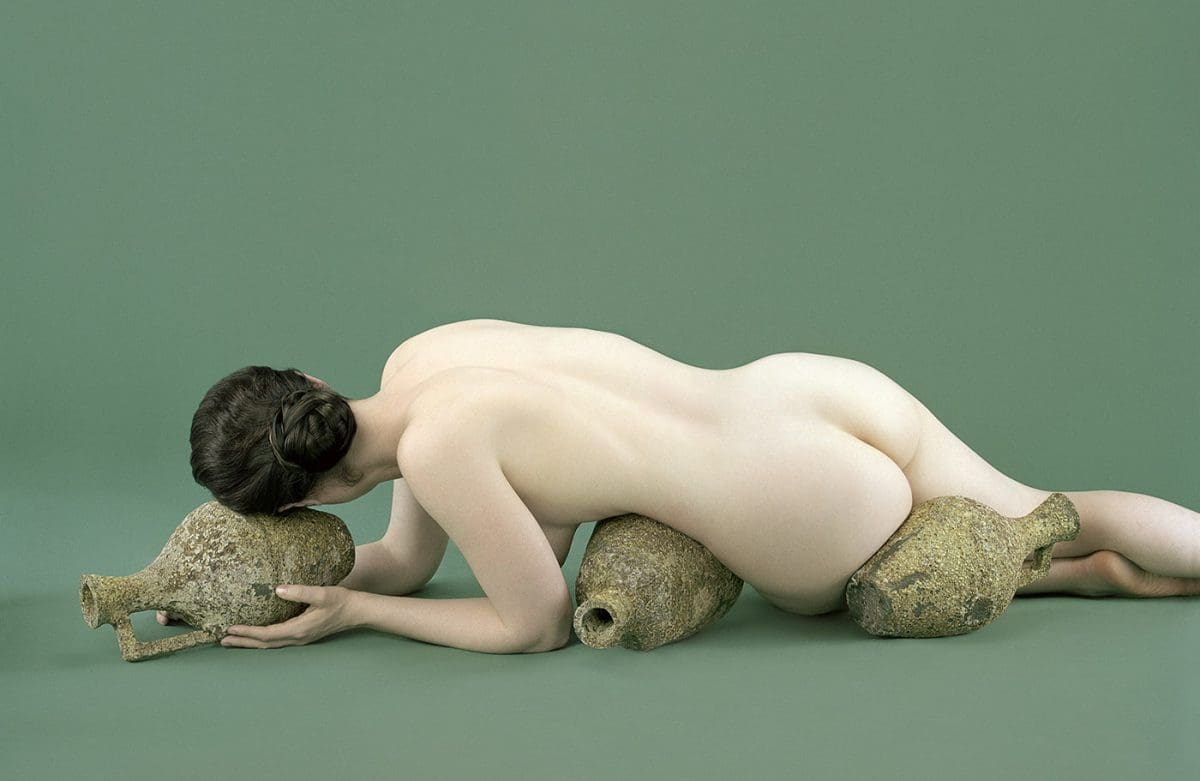

In a similar way to Papapetrou, Petrina Hicks also engages in meticulous staging to produce portraits imbued with a marble-like beauty. Spanning the trajectory of her photographic practice since 2003, Bleached Gothic is curated by Dr Isobel Crombie, assistant director of curatorial and collection management at the NGV, and contains over 40 photographs and videos. Harking back to Hicks’s former career as a commercial photographer, the crisp veneer of her images recalls slick advertising campaigns and glossy fashion magazine spreads. Seeking to reassess what it means to be female, Hicks’s images appear unblemished, yet on closer inspection, reveal imperfections cracking into their luminous façade. “There are blemishes in the seemingly faultless models,” says Crombie. “A fading bruise, a wound or tousled hair – all is not as perfect as it first appears.” Intensifying the visual impact of her pristinely flawed images, several of Hicks’s photographs have been reproduced in the gallery space as wallpaper panels reaching from floor to ceiling.

Crombie points out some viewers can be quick to assume Hicks’s images are about blossoming sexuality with their appealing pastel colour palette and props of shells, birds and wolf-like dogs. Referencing Venus, 2013, a portrait of a white-haired girl holding a huge conch shell over her face, Crombie explains Hicks’s intent goes deeper than that, ultimately challenging how women and children are visually represented in culture and history. “Her work often disrupts the symbols and imagery associated with the female form, ideals generally created by male artists and critics,” Crombie says. “For Hicks, a work like Venus is much more personal and less sexual. It suggests to her a woman obscuring her identity with an object symbolic of her womb, as if asking, ‘is this all I am, a walking womb?’”

Accompanying the exhibitions and shedding new light on each artist’s practice are two extensive monographs. Bleached Gothic is the first survey exhibition of Hicks’s career, and for the exhibition monograph, the NGV have combined full-page images from Bleached Gothic with excerpts of poetry by Sylvia Plath. For Olympia, the NGV worked closely with Papapetrou’s family to produce an intimate insight into her creative process. Her children, Olympia and Solomon, write about how they came to collaborate with their mother and Papapetrou’s husband, Robert Nelson, and detail the road trips the family would take to find the perfect outdoor location for a photoshoot. Susan van Wyk says compiling the monograph after Papapetrou’s death in 2018 was a moving and memorable experience. “Having all the family contributing essays to the book has made it become a very personal thing. Now Poli is gone, this book feels especially important.”

Olympia: Photographs

Polixeni Papapetrou

Bleached Gothic

Petrina Hicks

National Gallery of Victoria NGV Australia

27 September—29 March

This article was originally published in the September/October 2019 print edition of Art Guide Australia.