Piercing the veil

A new exhibition at Buxton Contemporary finds a rich complexity in the shadowy terrain between life and death.

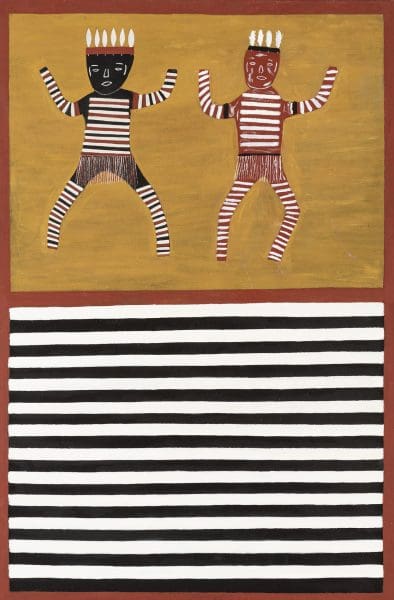

Alair Pambegan, Winchanam Clan Body Design: Bonefish Man & Dancing Spirit Man – Winchanam Ceremonial Dance, 2020, ochre and acrylic binders on linen. Image courtesy of the artist and Wik & Kugu Arts Centre, Aurukun.

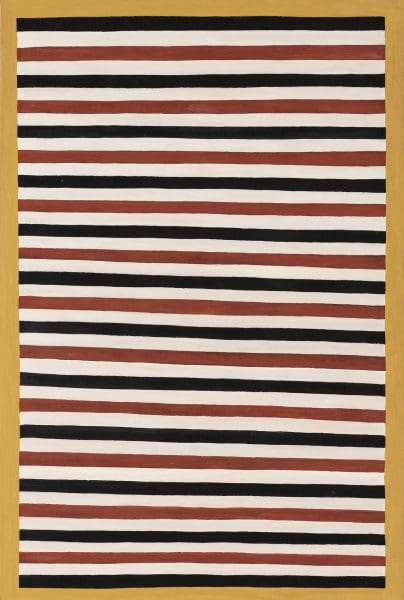

Alair Pambegan, Winchanam Clan Body Design, 2020, ochre and acrylic binders on linen. Image courtesy of the artist and Wik & Kugu Arts Centre, Aurukun.

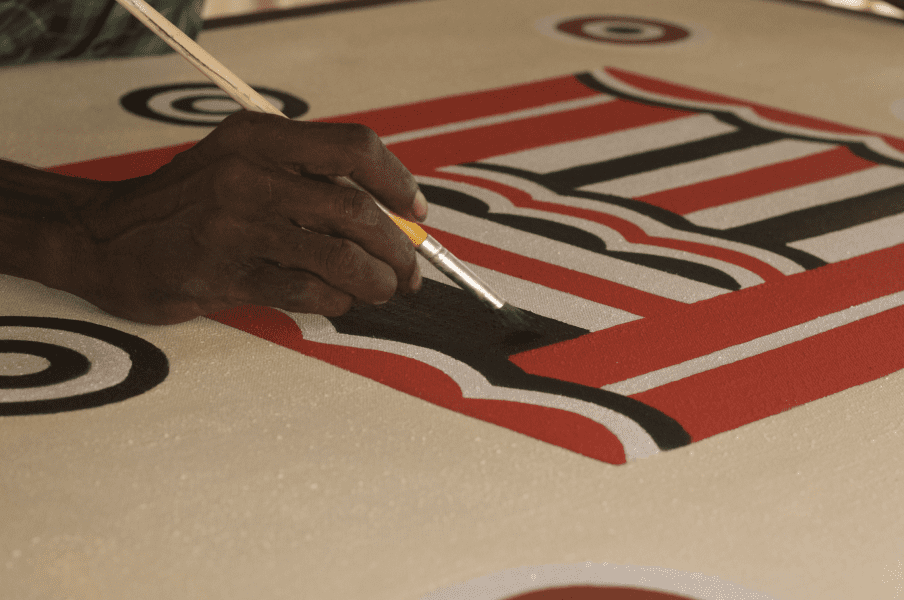

Alair Pambegan, 2020. Image courtesy of Wik and Kugu Arts Centre, Aurukun.

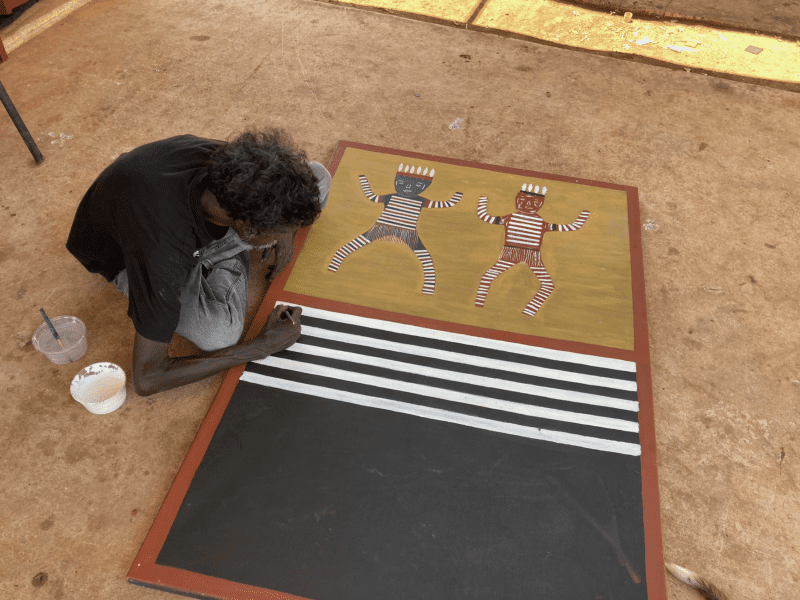

Alair Pambegan, 2020. Image courtesy of Wik and Kugu Arts Centre, Aurukun.

Aurukun is a remote township in north Queensland. It is situated where three rivers, the Archer, Watson and Ward, meet the Gulf of Carpentaria; the convergence of so much water is dramatic when flying into this settlement of 1200 people. My arrival, at the end of April, is at the tail of the wet season (Kaap). The Cape is lush; stretches of forest are interrupted by narrow ribbons of red dirt road, occasional sand flats, and the reflection of water from under trees in low-lying areas. The temperature hovers just below 30 degrees during my days here, a ‘cool change’ from the humid highs of the week before.

You can walk the perimeter of this township within the hour, its red dirt and bitumen streets fencing suburban-sized lots of high- and low-set houses. At the Wik and Kugu Arts Centre, a stone’s throw from the school and handy to the shop, artists arrive early. Power tools echo through the woodshed; in the painting/weaving studio the fan is a constant roar. Some days there are forays for materials. Artists head into the forest to fell a milkwood tree for carving. When the trailer groans out of the bush with a load of chopped timber, the trunk of the felled tree weeps with the white sap that gives it this name: thanchal.

Ochre for painting is gathered from locations on Country, and I witness the long, slow cooking— over four hours—of the yellow ochre (pip wu’) on a constantly stoked fire. Miraculously ‘Aurukun’ red emerges from these coals, is smashed into pieces, and is then ground and sifted to a fine powder. Mixed with water into a paste-like consistency, it’s transformed into the rich, grainy paint that Alair Pambegan uses to unerringly inscribe the arc of a circle on his canvas. Every brushstroke evokes centuries of tradition, stories and people of the past, while also capturing the artistic innovation for which Pambegan is known.

This red ochre is one of a small range of traditional ochres Pambegan uses exclusively: the others are yellow, black and white. He paints slowly, resting the canvas on the table, and is informed by his psyche and family line alike. His imagery is drawn from the traditional Winchanam clan body painting designs, which were passed down by his father, the great artist, lawman, and Elder, Arthur Koo’ekka Pambegan Jr (1936-2010). As Pambegan works, his teenage son Arthur Jr watches on; aware, in this place, of the legacy that continues to be integral to sacred, cyclical and social rituals.

Pambegan is versatile, his movements graceful and considered. He paints canvases in abstract styles related to body painting designs, and carves stories from the Bonefish (Walkain-aw) and Flying Fox Story Place (Kalben), which are tied inextricably into his Country, close to the Archer River. In the old days, men would make carvings secretly in the bush; they were believed to be divine creations that emerged for ceremony. Pambegan tells me that, while now so much is known, he still thinks about the secrets “going out on my Country just across the river”. And Pambegan does cross the nearby river whenever he has opportunity—and access to a boat.

A highly successful and deeply revered artist, Pambegan’s 2020 painting Winchanam Clan Body Design: Bonefish Man & Dancing Spirit Man – Winchanam Ceremonial Dance was selected for Cairns Art Gallery’s exhibition, Ritual: The Past in the Present, as part of the Cairns International Art Fair (CIAF). Artists were chosen for their ability to comment on and interpret, as the gallery says, “complex issues of cultural and personal identity”.

In this painting Pambegan innovates on his Flying Fox Story Place (Kalben), a salutary story about two brothers undergoing initiation rites, who hunt flying foxes in defiance of the order of their Elders. Discovered cooking these animals in a bush oven, they are punished when bats explode from the ground to carry the brothers into the night sky. Today they remain visible in the Milky Way. As Pambegan explains, “The spirit man dances at night, always makes fire, and dances corroboree.” Pambegan’s canvas captures the body paint of the dancers dramatically repeated in the stripes that band the bottom half of the canvas, and their repetition is lively.

Recently, in 2018, Pambegan’s highly regarded bonefish and flying fox carvings were exhibited in the 9th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art in Brisbane. “I always do bonefish,” explains Pambegan. “I talk to my cousin brother, but he is always busy, calling out, flying.” New carvings made from the harvested and dried milkwood, in collaboration with artist Nathan Ampeybegan, evoke the swarm of bats moving through the air, and assert the continuing importance of cultural law. Bonefish canvases will also be seen at CIAF, the sharpness of their execution echoing the strength of their streamlined shape and speed.

Pambegan works with quiet confidence, driven by this heritage. Seasonal change is dramatic in Aurukun, but the unfolding of culture is steady, led by artists like Pambegan who continue to practice the stories associated with the sacred rituals, which have been taking place since deep time.

Ritual: The Past in the Present

Cairns Art Gallery

15 May—22 August

Cairns Indigenous Art Fair

Various locations

17 August—22 August

This article was originally published in the July/August 2021 print edition of Art Guide Australia.