The world is always ending, but the Biennale of Sydney isn’t being fatalistic or vying for a doomsday narrative—instead, they’re exhibiting how communities and artists from around the world have always shown resilience in the face of war, environmental disaster, diaspora and colonialism.

As the artistic directors Cosmin Costinaș and Inti Guerrero (read our interview with them here), stated during the Biennale preview, it’s about how communities embark on ways of overcoming and that “through the power of imagination, community and art… these moments have not been of ending or apocalypse, but instead are processes of imagination”. From large-scale vibrant works to celebratory pieces, to quieter creations, the Biennale brings together myriad cultural and aesthetic forms—here’s what you must see.

White Bay Power Station

It is not uncommon for the Biennale to offer a wildcard venue, and this time it’s White Bay Power Station. Previously one of the longest-serving coal-fired power stations in Sydney, it has the complicated history of industry and colonialism that the Biennale is unpacking (and it’s $100 million dollar restoration has an aesthetically chic, warehouse atmosphere). The curation feels superb from Dylan Mooney’s large-scale portrait of gay activist Malcolm Cole as Captain Cook to Kaylene Whiskey’s jumbo-sized television set. There are kites by Orquídeas Barrileteras, a light installation by Darrell Sibosado that holds the contemporary and traditional—and so much more. Also, don’t forget to look up.

The end of the world at the Art Gallery of New South Wales

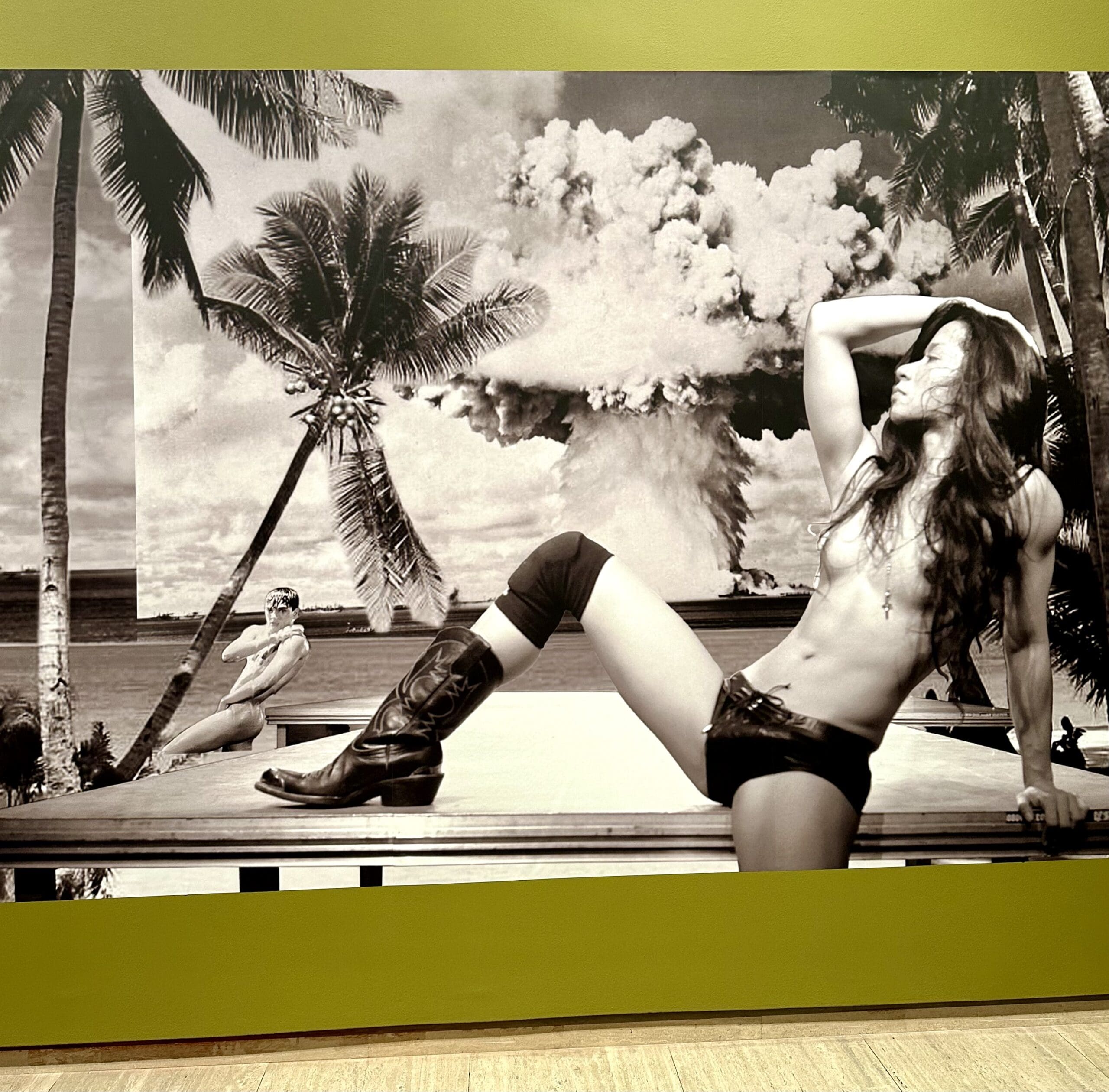

If apocalyptic thinking is being repositioned in this Biennale, then war, bombs, and violence must feature in the discussion. One room at the Art Gallery of NSW captures this. There’s Kazakhstan-based Saule Dyussenbina’s wallpaper that speaks to the 459 nuclear tests made between 1946 and 1986 in a previously Soviet Union region of her country. There’s Gordon Hookey’s video in which kangaroos launch nuclear missiles at a government building and Eisa Jocon’s large-scale digital print where the artist poses Playboy-style against a backdrop of palm trees and nuclear bombs.

Eric-Paul Riege at White Bay Power Station and Artspace

Diné/Navajo weaver and fibre artist Eric-Paul Riege has two installations, each designed as large-scale textile earrings, made “for the gods”. The piece at White Bay Power Station hangs from the ceiling and reaches the floor, spanning multiple levels of the building, so there’s new perspectives on each level. The works in Artspace exist in smaller form, likewise hang from the ceiling—there’s something beguiling about their swaying existence.

Riege will be interacting with the weavings in a performance happening during the opening weekend.

Nikau Hindin at White Bay Power Station and UNSW Galleries

Te Rarawa/Ngāpuhi artist Nikau Hindin’s sculptural pieces are made with ancient Māori techniques that have been out of practice for over a century, using a labour-intensive process that transforms the bark from paper mulberry plants into a cloth that is then used to make kites and other material works. Her kites are hanging in the UNSW Galleries, and their delicate beauty is a welcome moment of quiet consideration. She is also part of an installation at White Bay Power Station, alongside fellow barkcloth artists Ebonie Fifita-Laufilitoga-Maka, Hina Puamohala Kneubuhl, Hinatea Colombani, Kesaia Biuvanua, and Rongomai Grbic-Hoskins.

William Yang at Chau Chak Wing Museum and UNSW Galleries

William Yang is one of Australia’s most beloved photographers. Primarily known for his explorations of sexual and cultural identity through his documentation of Sydney’s gay subcultures over the last five decades, his works featured in the Chau Chak Wing Museum are exquisite examples of this. The photographic series shows a group of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander dancers performing a work titled Forward to the Dreamtime outside the Sydney Opera House in 1976. The choreography of this performance led to the establishment of the Aboriginal Islander Skills Development Scheme (AISDS), which later became NAISDA dance college. The movement captured in Yang’s photographs is breathtaking. And he also has another photo series at UNSW Galleries.

Serwah Attafuah at the Museum of Contemporary Art

Serwah Attafuah wins the “Best Frame of the Biennale” award, hands down. She was commissioned to create her largest work yet for the Biennale, and the result is Between this World and the Next at the MCA, an Afrofuturist, surreal cyber dreamscape of epic proportions. The work spans eight screens of digital animation housed in a gaudy, gilded frame that is almost baroque, but is actually repurposed tech junk—laptops, video cameras, e-vapes—all spray-painted gold. It’s dazzling.

Citra Sasmita at Chau Chak Wing Museum

Have a close look at Indonesian artist Citra Sasmita’s painted traditional Kamasan canvases, which are draped from the Chau Chak Wing Museum’s ceiling. The installation is striking from first glance, but when you get underneath and examine the details it takes on a whole new meaning. Her depictions of female bodies challenge the patriarchal preconceptions inherent in colonial narratives of Balinese women, making women agents of power and resistance.

Anne Samat & Kirtika Kain at the Museum of Contemporary Art

Anne Samat and Kirtika Kain are housed in the same room of the MCA. Initially their commonality seems like scale, but look closer. Malaysian artist Anne Samat’s brightly coloured and heavily adorned installation is bejewelled with the heads of plastic rakes, and other dollar shop items. Delhi-born Australian Dalit woman Kirtika Kain paints the most exquisite, mottled canvases. Her materials are often sourced in Indian grocery stores—rice, turmeric and beads are paired with pigments and gold leaf. The unmissable works speak to cultural heritage and how art stems from the most surprising of materials.

Pacific Sisters at the Art Gallery of New South Wales

The garments created by the Pacific Sisters—which exist between fashion, activism and sculpture—are such exciting, potent imaginings of what clothing can be. The four elaborately adorned, commanding garments feel as if they’re about power itself. As one of the Biennale directors explained, they’re spiritual but also centre “queer, feminist and radical disobedience”. Founded in Auckland in 1992, the Pacific Sisters embrace their Maori, Pacific and queer identies in their work, with artists in the collective including: Lisa Reihana, Rosanna Raymond, Ani O’Neill, Suzanne Tamaki, Selina Haami, Niwhai Tupaea, Henzart, Henry Ah-Foo Taripo, Feeonaa Wall, and Jaunnie ‘Ilolahia.

Sana Shahmuradova Tanska at Artspace

Ukrainian artist Sana Shahmuradova Tanska has painted compelling scenes that seem to fluctuate between the spiritual and violent. There are figures ambivalently embracing, an unnerving spirit, and a woman caught between salvation and fire. As Tanska’s artist statement explains, she “is focused on paintings and graphics where she explores her roots, using trauma as a method of communicating with ancestors. . . Recent works highlight atrocities and violation of nature and inhabitants committed by the aggressor, with an emphasis on the similarity of brain activity while visualising both future and past.”