Material curiosities: Primavera 2025

In its 34th year, Primavera—the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia’s annual survey of Australian artists 35 and under—might be about to age out of itself, but with age it seems, comes wisdom and perspective.

It was 1979. Photographer William Yang made eye contact with the young, curly-headed man. The music was loud, so Yang leant over to shout his opening line as a prelude to buying him a drink, but the young man shook his head, and wrote three letters on his own palm: J. O. E.

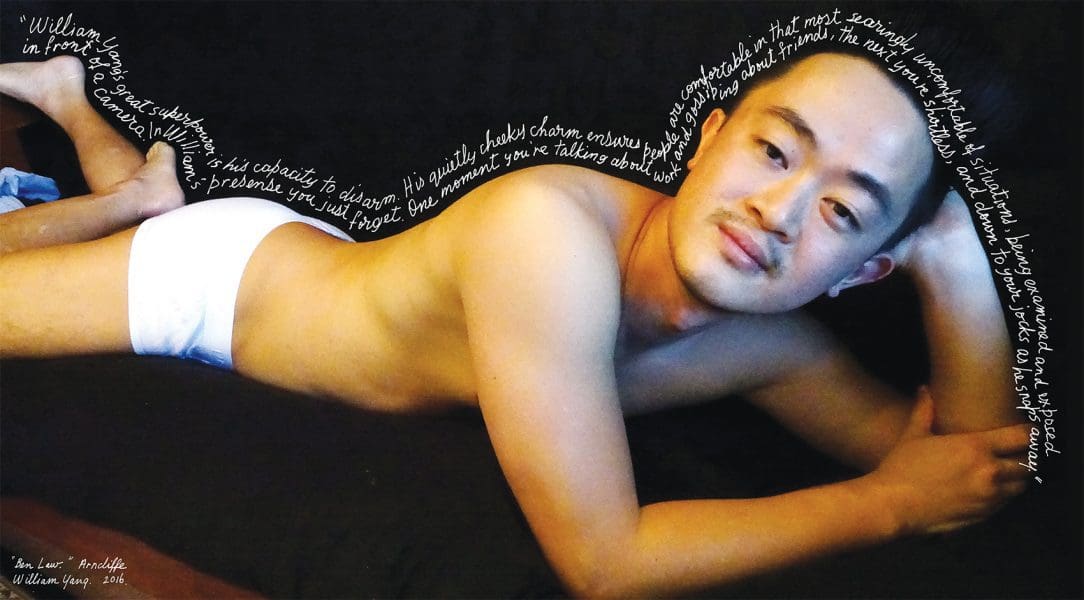

Joe was deaf. The country town labourer had come to the city, Yang learned. They went home together. There was little need to talk. The young man proved shy in bed, but Yang liked him. The next morning, Yang photographed Joe sleeping. Later, he wrote the story of their encounter on the image in black ink, across Joe’s back, in a pictograph narrative style that he made his own across his artistic career.

Now, more than 40 years later, during the COVID-19 lockdown, Yang revisited the story of Joe, the man he put into a taxi the next morning and farewelled. At an appropriate social distance from his teacher, he has learned Auslan, the sign language of the Australian deaf community, in preparation for making a video in which he tells the story of encountering Joe with spoken words and signing, as part of a large retrospective of his work at QAGOMA in Queensland.

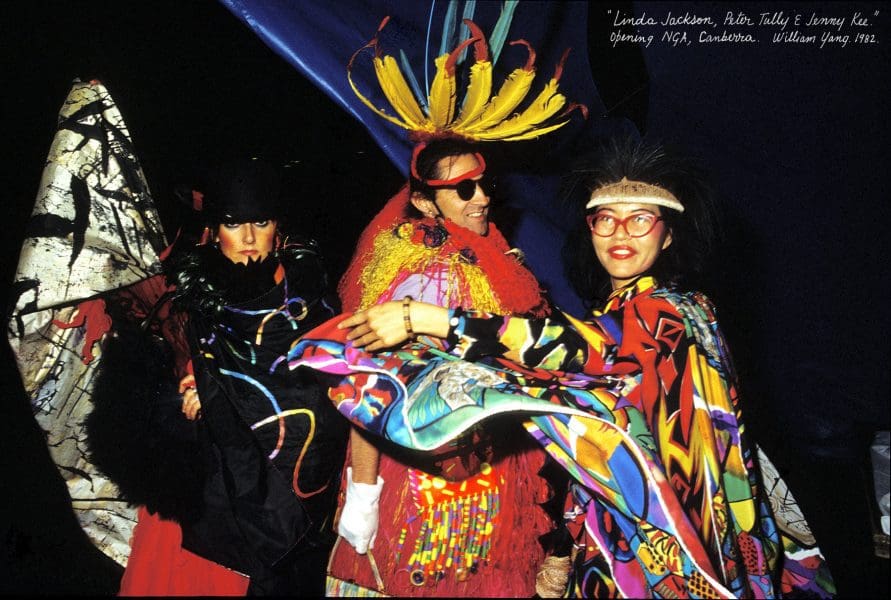

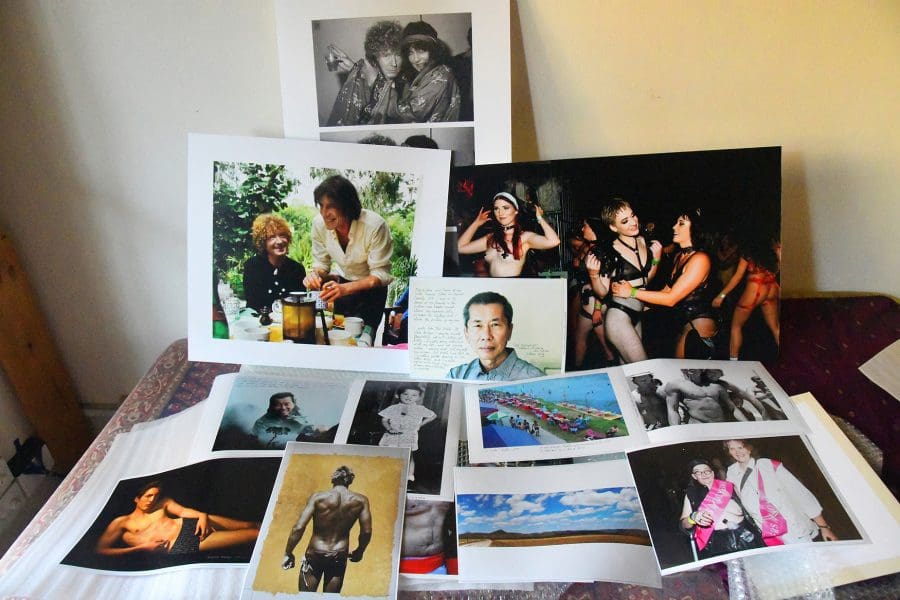

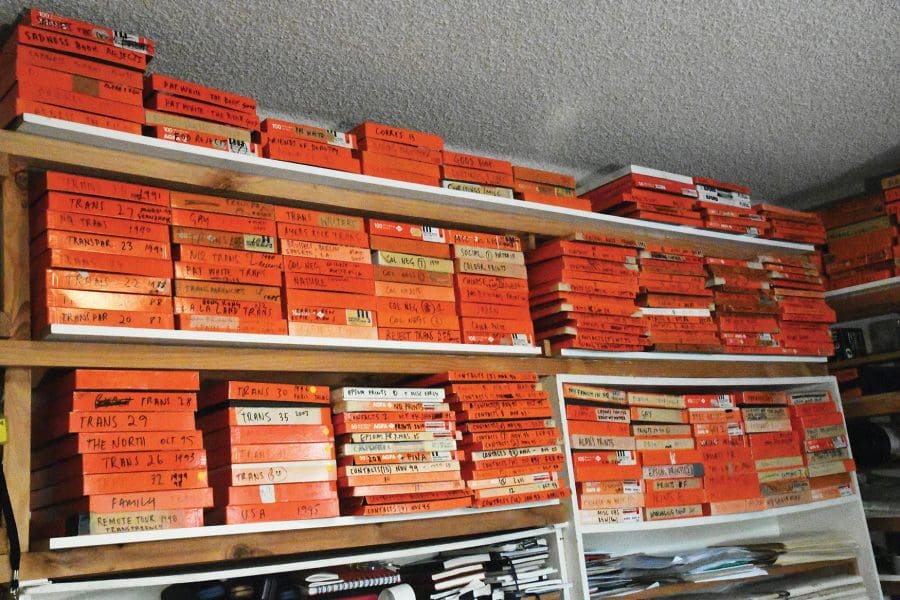

Yang’s long career has included not only his photography, but ten live performance pieces, including Sadness, Friends of Dorothy, Blood Links and My Generation, all four of which have been made into documentaries. Currently screening on streaming service Kanopy, these four documentaries vividly showcase Yang’s commitment to capturing the queer social scene, the Sydney Mardi Gras, the AIDS crisis, his Chinese-Australian forebears and his childhood growing up in Queensland.

In a 2016 monograph on the photographer, William Yang: Stories of Love and Death, authors Edward Scheer and Helena Grehan comment on Yang’s “calm and neutral” presentation style in these performance pieces: “Through his own stillness he makes room for others to move and be moved.” But Yang learned that Auslan requires him to be less of a deadpan performer relying just on voice and story. “When you’re signing, you’ve got to be expressive, because that’s the main communication,” he muses now. “It’s all exaggerated. I’m finding that exciting, because it is a new type of performance.”

During this epoch, Yang has mostly taken a break from photography—before the coronavirus pandemic, he was typically photographing guests in theatre lobbies and art exhibitions three nights a week. But turning 77 this year, he’d been considering scaling back his social rounds anyway, to conserve energy. He’s still fit, bicycling around paths near his apartment in Wolli Creek, in Sydney’s inner southwest, and has been socialising on Zoom conferences.

As achingly conveyed in his documentaries and performance pieces, Yang lost lovers and friends to the AIDS pandemic. The potential impact of COVID-19 in Australia also crossed his mind. “It’s different from AIDS, which was much worse,” he says, “because there was a lot of stigma attached to AIDS. If you were gay, then you were vilified. If you were gay and had AIDS, then you were a total pariah.

“At that stage, AIDS was a death sentence. This pandemic [COVID-19] is not as difficult to negotiate. It’s still scary, and there are restrictions. But AIDS was really fearful, and you were subjected to judgement and hate. Since COVID-19 is across the board, there is a sense of solidarity amongst everyone, whereas that certainly wasn’t the case with AIDS.”

In his retrospective, for the first time, Yang publicly tells the story of his long-distance relationship with his boyfriend of 23 years, Scott, who lives on the Sunshine Coast.

Ten years ago, for a Valentine’s Day newspaper story, Yang told me he was married to his work and found romance overrated, but that Scott had caught his attention when they met through one of the photographer’s performances. “He’s tall, with a beard, with nice eyes and sensitive eyebrows; well-shaped rather than thick. He has a soft masculinity. He’s also got a trait essential for people I have a relationship with: he can read a book, so he can be in the same room as me and not demand attention.”

Yang is an adherent of Daoism. Has spirituality been important to him in these strange times? “Only in that it’s part of my philosophy,” he says now. “I’ve tried not to be swept away with the panic of it all. If we think about Daoism, I just try to apply it to my daily life: I suppose it’s being mindful of everything. I’m kind of dedicated to my work, and I pour my energy into that, to make it the best I can.”

Seeing and Being Seen

William Yang

Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA)

27 March 2021— 22 August 2021

This is an updated version of an article originally published in the July/August print edition of Art Guide Australia.