Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

Shackled and awaiting the gallows at Fannie Bay Gaol at Palmerston in the Northern Territory from 1892 to 1893, Aboriginal stockman and ex-jockey Charlie Flannigan made the most of the rudimentary art materials—pencil and paper—the warders gave him during the last months of his life.

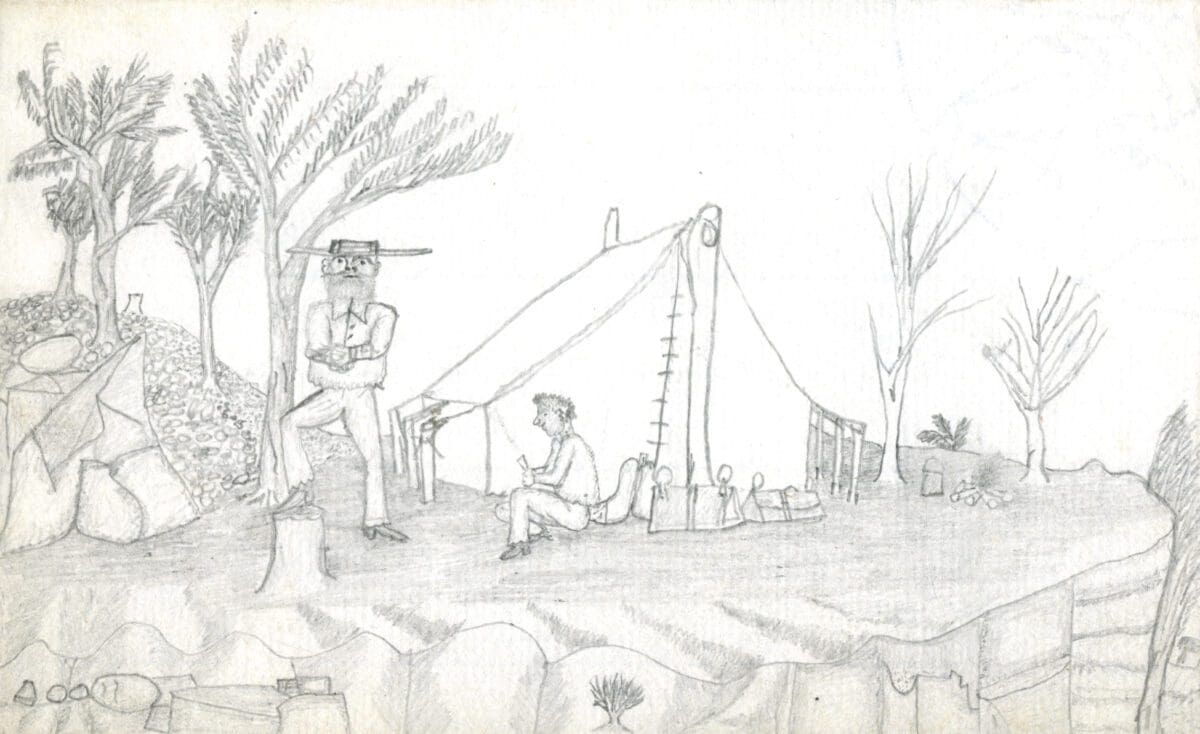

Using both sides of the paper, which he tore into postcard-size pieces, Flannigan drew vivid, detailed images such as a horseman leaping from a cliff, men camping with a tent in the Kimberley region, the SS Rob Roy sailing ship he had once travelled upon, and a Darwin streetscape.

“He was a very rare individual at that time,” says Don Nawurlany Christophersen, curator of A Little Bit of Justice – The Drawings of Charlie Flannigan, an exhibition of more than 80 of these works gathered from Flannigan’s cell after he was led away by authorities to become the first man officially executed in the Territory, on gallows erected in the prison yard.

“There were very few Aboriginal people travelling around anywhere in Australia that had their own horses—he had two horses, his own saddle, he had his own rifle. He had his own gear. He travelled around working at cattle stations, and no one controlled him. He was his own man.”

In his stockman and jockey days, Flannigan would point out when he was not treated with equality with white people, says Christophersen. “They thought he was a bit uppity, because he’d pull them up all the time.”

But in September 1892, Flannigan’s liberty to roam ended abruptly. One night during a game of cards, he got into an argument with a white cattle station owner, Samuel Croker, at Auvergne Station near the border of Western Australia. Christophersen says Croker had been bullying Flannigan, and self-defence may have been at play. “It was an argument that went bad. Both men had guns, both men went for their guns.”

Flannigan entered a not guilty plea to murder, believing he should have faced a manslaughter charge. Yet, reading the historical records, Christophersen believes Flannigan felt remorseful and melancholic, since he declined to defend himself in court, even while anti-capital punishment advocates wrote to the authorities, pleading that Flannigan be saved from execution. “This was a man who very rarely swore. He was quite pious.”

Christophersen believes racism was a factor in the jury’s controversial unanimous guilty verdict, with authorities wanting to make “an example” of an Aboriginal person. “It wasn’t about justice, it was about revenge,” he says. “Unfortunately for Charlie, he had about 10 months sitting in a cell. They kept him in manacles and handcuffs, and they wouldn’t let him out because they were understaffed at the prison.”

Christophersen says Flannigan came from central western Queensland, although he does not know from which Indigenous clan. He rediscovered Flannigan’s drawings when researching the story of the second man officially executed in the Northern Territory, Wandy Wandy—also an Aboriginal man—who was hanged in 1893, for an unrelated crime.

“When I asked for documents from the South Australian Museum, they said, ‘You’ll also want to see these drawings from Charlie Flannigan,’” he recalls, “I said, ‘Sure, yeah.’” Studying Flannigan’s drawings, Christophersen began to understand Flannigan was telling his story in images.

“He doesn’t show the [pending] execution or the killing of another man that he committed, but he does show his arrest. He [mostly] wanted to remember the good times in his life.”

The drawings left in Flannigan’s cell were likely considered collectible as a “macabre souvenir of someone executed”, says Christophersen. They were later handed to Alfred Searcy, the Northern Territory’s sub-collector of customs—one of 10 men who witnessed Flannigan’s execution—who passed them to the coroner, who in turn handed them to the South Australian Museum.

While drawings by incarcerated First Nations people from this period are a rarity, Christophersen says evidence of artwork by other roving stockmen can still be seen in situ. “All through the Northern Territory, Queensland and into Western Australia, you can see where stockmen have drawn—on the watertanks,” he says. “People had this want to tell a story.”

Today, Flannigan’s pictures stand as an important historical and cultural record, intriguing in their compositions from an artist likely self-taught to draw.

“Certainly, he had that eye for detail. He loved architecture, he loved horses. He drew a lot of the scenery of cattle stations and the buildings on cattle stations, but only two miniscule drawings of cattle. He was inspired to draw 13 images of the ship that he travelled on to Darwin, the SS Rob Roy, which are very close to technical drawing. He did one drawing of the Fannie Bay Gaol, and he wrote, ‘long fellow waves ta ta’. He was waving ‘ta ta’, goodbye.”

A Little Bit of Justice – The Drawings of Charlie Flannigan

South Australian Museum

(Adelaide SA)

On now—Until 10 September