Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

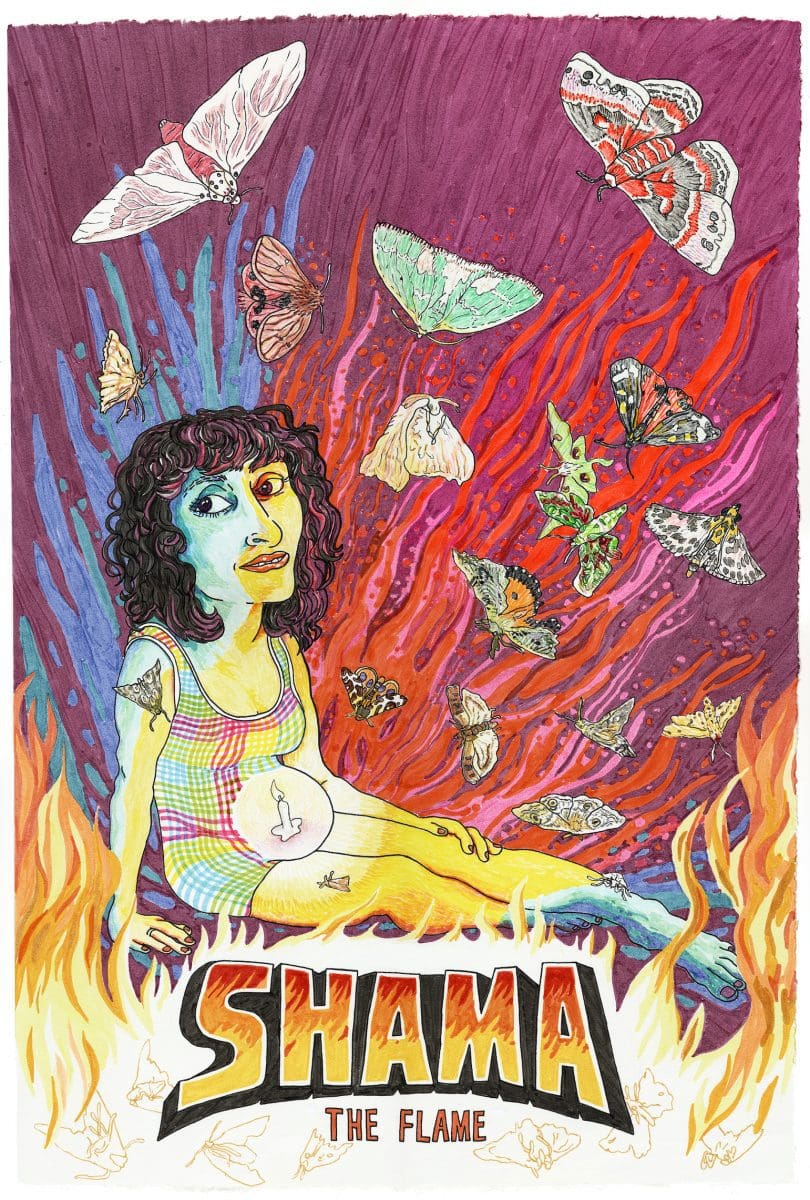

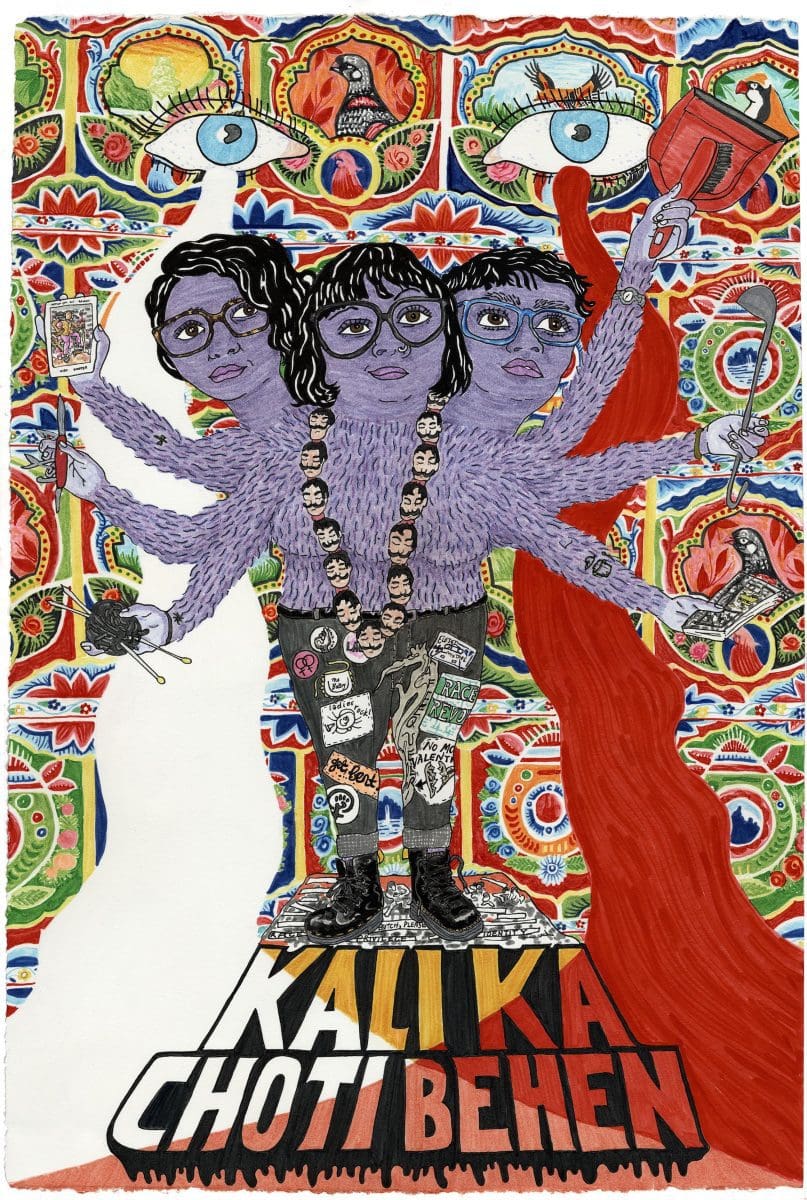

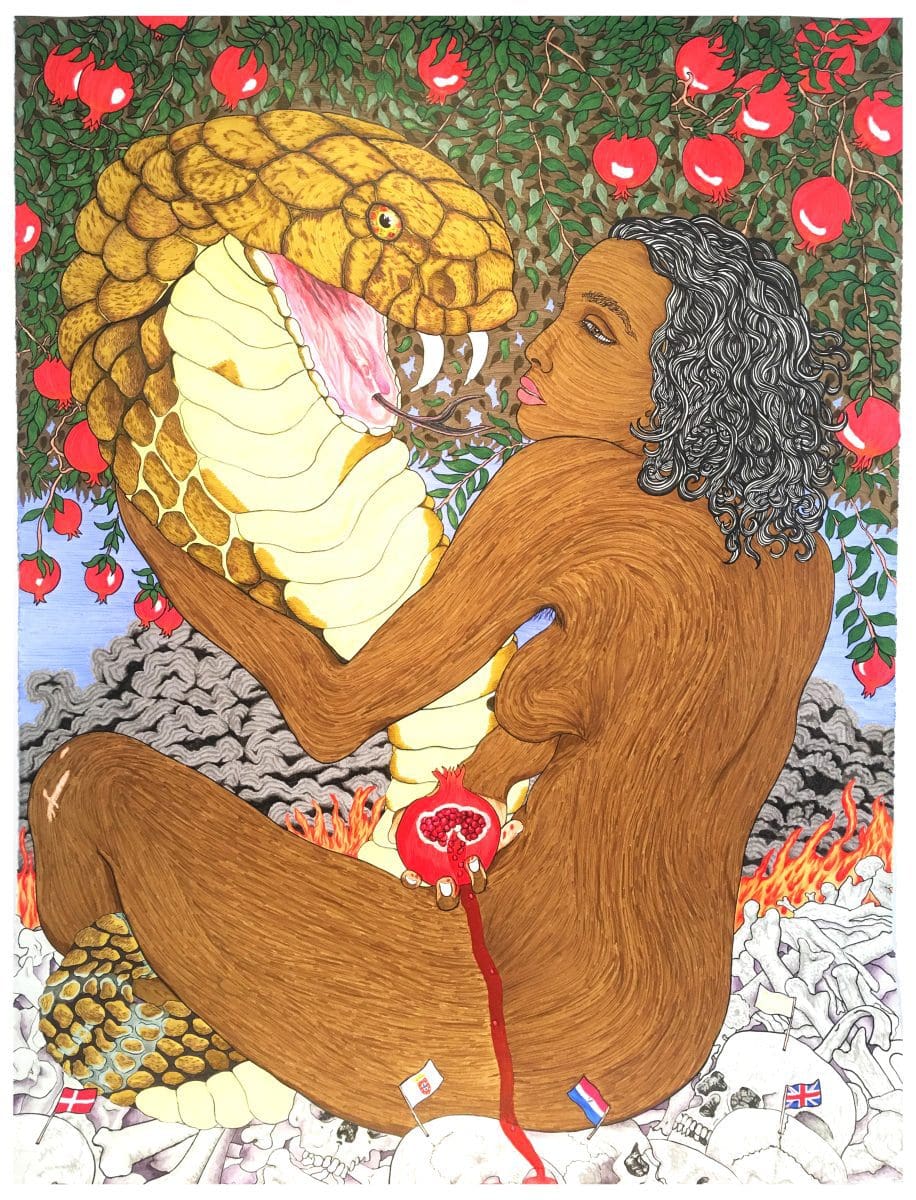

The striking, idiosyncratic artwork of TextaQueen has a life of its own. Working primarily with markers, the Melbourne-based non-binary artist creates bold, often irreverent depictions of diasporic experience. Their new show, Bollywouldn’t, skewers Bollywood archetypes by way of fictional film posters, starring other queer and trans South Asian people, presented as digital projections onto images of famous buildings around the world.

Giselle Au-Nhien Nguyen: You’ve worked across forms from photography to marker drawings. How has your practice evolved over time?

TextaQueen: In my fine arts degree, I mostly did photography and experimental video, but then I left and I didn’t have a $40,000 edit suite or a dark room, so I started drawing as my main practice. I’ve always done photography, just not as part of my exhibiting practice—I could not be an artist if the only thing I was doing was making giant works on paper for commercial and institutional spaces, because a big part of my art process (and why I want to be making art) is for the connections with people. Not only in the process, but also in who sees the work, and those kind of white wall spaces aren’t necessarily the places where I’m going to feel the deepest connection to people, or people are going to even be able to access that intimacy with the work.

What made me get back into it [markers] as part of my practice was when I was doing a residency and I was planning to work on a paper self-portrait series. I started taking photographs of myself in the landscape, and then I was like, “This is actually the work.” It’s also about the sustainability of my practice—I’m not only just talking financially, but also the emotional process. Diversifying my practice keeps me more dedicated to it and more enthused to keep making work.

GAN: You’ve spoken about the use of textas as subversive in the traditional art space—how does the medium speak to your ideas?

TQ: I started drawing with textas in my early twenties and it was this very accessible, affordable, ready-made way to create. I just liked what it invoked—it’s associated with this young, unskilled kind of creativity, so to be making complex work with it for me is subversive. It was another way to reference the paternalism that people in my body often experience in the art world, but actually bringing more complexity to that.

GAN: After having worked with the form for so long, how has your approach shifted?

TQ: My style has really changed—sometimes I miss the looseness with which I could draw in the beginning, but I feel like I’m so skilled with putting a marker to the page. I still draw the initial portraits from life, but I’ll often add a lot of details from reference photos and research, especially when I’m composing stuff that has a big design element. In the beginning, it was just colour by numbers style, where I would draw the outline and colour them in, and now I use a really big range of techniques and different kinds of markers.

I sometimes use a waterbrush or watercolour pens, and just do a lot more fine rendering and a mix of graphic colouring. In the beginning, I also used Crayola markers, and now I use artist pens that are archival, which came about because in the beginning when making big works, I’d be using a red marker in a kids’ pack and then I’d open the next kids’ pack because that one’s run out, and it would be a totally different red. So, I had to buy markers where I know they’re all the same colour. I know so much about so many artists’ markers—which ones will look flat and which ones I can blend.

GAN: How do expressions of gender fluidity influence your work?

TQ: What I represent in my work really reflects my life, because my work really reflects what I am personally going through, what is happening around me and the world that I connect with. Ideas of gender fluidity have come up more in my work as that’s been something I’ve felt more comfortable identifying with, and the community who I’m connecting with are subjects of my drawings. It’s kind of like language—I think it was there, but I didn’t have the language or the ease to express it.

GAN: You’ve drawn yourself as different iconic figures—what does this express about your own identity and a collective identity?

TQ: I have done a lot of self-portraiture, but I’m really trying to talk about collective experience and experiences that aren’t just personal but are systemic. Drawing myself as Jesus or Gandhi crystallises that. I grew up really Catholic and it was a deep thing to draw myself as Jesus. I hope people understand the complexity of drawing myself as Gandhi when he is this super iconic figure [but] that is a really complicated character who did a lot of dodgy things.

I was really thinking about how celebrity dehumanises people and doesn’t allow for complexities—it’s either you’re on the pedestal or you’re paternalism. I feel that personally; how isolating it can be that people have an impression of you from your work or from the persona they imagine about you. And I think that’s an experience that’s so much broader now because of social media, where any individual with a following can experience those kinds of things.

GAN: Your new show centres on Bollywood—what’s your relationship with it?

TQ: The exhibition is called Bollywouldn’t because it’s about what wouldn’t and doesn’t happen in Bollywood and beyond. I asked queer and trans South Asians I met when I was in London in 2019 on a residency to come up with ideas for a fictional Bollywood poster and about their intersectional identities, deconstructing the ‘isms’ of Bollywood and the world.

Honestly, I haven’t seen more than maybe two dozen Bollywood movies, and a lot of them I’ve seen since I started doing Bollywouldn’t. But growing up, the pressure to assimilate and connect with anything Indian as a kid was so fraught because I was never going to be enough, either so-called Australian or Indian, so my relationship with Bollywood had that dynamic to it.

I was queer, and I didn’t have the language to know that—but even now watching movies, I feel so alienated from the hetness [heteronormativity] of it. I really liked it as a format to parody and to connect with, because of the cultural connection and the drama and the design. It felt like everyone who I asked also had a fraught connection to Bollywood because of similar reasons, but then found the process of coming up with the portrait and posing for it as a way to connect with it. It felt like an appropriate way for us to reclaim this cultural form.

GAN: What kinds of conversations were you having with your subjects for the film posters?

TQ: I had some ideas for portraits that I suggested to people, but everybody came up with their own idea. I was really excited by a few ideas, and some people came with very formed ideas; I asked one person who was like, “I want my friends in it and we want to have three heads and each of our arms is going to be holding different things that are to do with our punk organising background.” They really connected with me throughout the process of drawing. It was a very intimate and organic process where I’d ask them about what their connection was to the genre, to their culture and heritage—a lot of conversation about queerness and culture and asking them to represent what they feel isn’t represented.

GAN: Where did the idea of projecting the images onto buildings come from?

TQ: I have photographs of various sites that the models have chosen in the UK, mostly in London, and the portraits are appearing as murals on those buildings via digital manipulation. It’s a fictional landscape of the buildings with the murals of the portraits on them. I asked each of the models where they’d like to be that related to the content of their portrait.

The idea for how these portraits have been presented as the photographs on the buildings came out of extended lockdown and things like Black Lives Matter, and people reclaiming public space and agency. It was just the surrealness of life at that time. By creating these works, it really convincingly looked like these portraits had been put on the side of the Tate. I found myself imagining worlds.

GAN: You’ve had residencies in the UK and in India—how does the art world there differ to here in Australia?

TQ: My residencies in India and in the UK both personally and creatively impacted me. It was the first time I’ve been to India since I was a teenager at a very different time in my life. Going there and experiencing all this disconnection and connection, and being in a residency as the only artist there who’s actually culturally connected to the continent, and really feeling concretely like my privilege was so much—it really, really impacted the work that came out of there. I went to London, for a few days, a year before I applied for the residency, and I felt surprise and relief there—so many other South Asian queers close to my age are doing creative and political stuff that I could relate to, and there’s the intergenerationality of community that I don’t get to experience here at all in relation to being South Asian because of the recentness of immigration.

GAN: The Australian art world is diversifying but it’s still largely grounded in notions of colonialism and whiteness. What kind of meaningful changes would you like to see?

TQ: I went to a conference in London called ‘Decolonising the Cultural Institution’, and the question could not be answered because I don’t think it’s possible. I’m really trying to build stuff that is not reliant on the career model of commercial representation and institutional shows. I want more people to find other ways of creating outside of the institution where they’re still supported. I hope to straddle my contacts in the capital-A ‘Art World’ and to be able to connect with them from a more punk mindset.

The makeup of institutions needs to change. When the institutions are choosing who to employ, they’re going to employ the most palatable people of colour anyway, and sometimes it’s almost more painful when there’s someone that looks like you in positions of power that are just empty of the capacity to make any change. I have a lot going for me to be able to do stuff outside of those spaces because I’ve been in them before, but that’s what I vote for—to dream new ways outside of institutions.

Bollywouldn’t

TextaQueen

4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art

(Sydney NSW)

22 October—18 December

This article was originally published in the November/December 2022 print edition of Art Guide Australia.