Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

Our Common Bond brings together artists who face “being Australian in some circumstances and not being Australian in others,” says curator Olivia Welch. “They’re Australian, but not ‘enough’.”

Welch is interested in the “prefixes” we use to explain our identity, when these additions are expected—or demanded—and when they are not. She has taken the exhibition title from a booklet for people taking the Australian citizenship test. “You can download it from the internet. We can all see it, although we never do,” she says.

Pamela Leung’s suite of works is based on words she heard over 40 years ago, when she first moved to Australia from Hong Kong. They were “basically go back to where you come from,” Welch says. Leung has turned the words into a sort of poem. One of the works is neon, the others are tattooed in different languages on to vellum. For Welch, the works represent “this idea of it sticking with you and being a marker for life.”

Siying Zhou’s Pie-pai videos from 2013 show her using chopsticks to dissect a meat pie and a cheese and tomato toastie. “They’re quite beautiful works, watching her navigate taking off the lid of the pie, scooping out the filling, cutting up the pie lid,” says Welch. “She’s deconstructing an Australian thing and making it Chinese, but it will always obviously be a hybrid.”

Hybridity is also expressed in Atong Atem’s portraits. Atem uses “a style of colonial portraiture that exoticized African people but then became a widespread photographic aesthetic that people adopted and really embraced,” Welch explains. Atem also dresses her sets and subjects in a colourful wax print textile that has a complicated Dutch and African history.

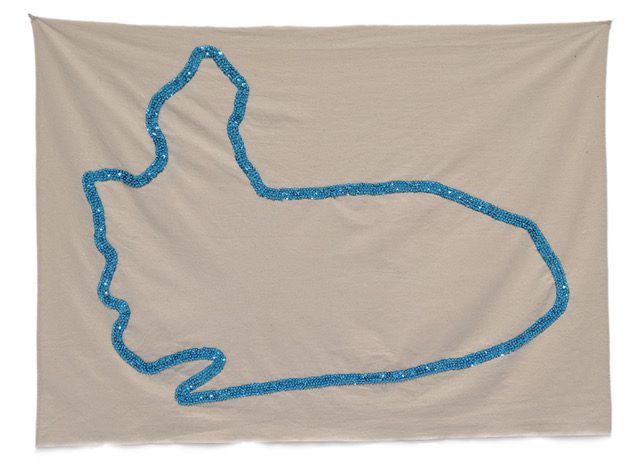

Duha Ali uses textiles in a very different way. Her work is made using a Kurdish embroidery technique taught to her by her aunt and mother. For Ali, her Australian citizenship means a place where “she’s allowed to keep familial and cultural customs alive and she hopes that it stays that way,” says Welch.

For obvious reasons, there’s a different dynamic at play in the work of First Nations artist Amala Groom. In Lest we… get over it, 2017, Groom splices together footage of politicians and media personalities like Alan Jones and Kyle Sandilands. The result is unexpectedly positive, a “heroic message about Aboriginal people, said by people who are known for saying negative things,” says Welch.

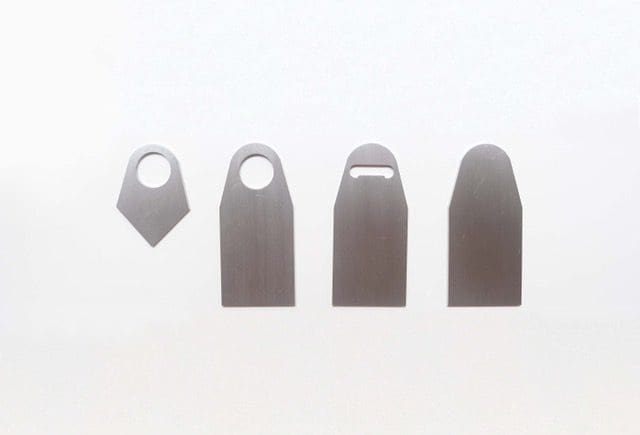

There are reminders of how high the stakes are throughout Our Common Bond. Lara Chamas explores Islamophobia, and Jason Phu responds to a goldfields massacre in ROLLING ROLLS ROLLED ROLL, 2018. By pairing the word “roll” with random objects, Phu highlights the horrifying absurdity of a banner used at the time of the massacre that called, “Roll up, roll up, no Chinese.”

For Welch, the examination of identity in Our Common Bond is both timely and necessary. “This is reality and I think it’s important that these realities are considered by everybody.”

Our Common Bond

May Space

10 April – 5 May