Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

An abandoned seaside motel stands in Port Dickson, Malaysia. After being sold to foreign speculative buyers in the 1980s, it now sits in ruins, overgrown with foliage. Yet there is also creation; it’s the site that artist Simryn Gill, who looks at the relation between history, place and experience, has been working from. Producing photographs and monoprints that trace the minutiae of the motel’s fading remains, such as white bathroom tiles and the crevices left by copper piping theft, Gill places ink directly on the motel’s surfaces, imprinting onto cloth the negative spaces left by grooves and cracks. The Singaporean-born artist, who works between Malaysia and Australia, creates images that trace memory and site.

Gill is one of six artists showing at TarraWarra International 2019: The Tangible Trace. With a global outlook, the exhibition comprises artists who collectively imagine, document and experience the world via an echo or remnant, including Francis Alÿs (Belgium/ Mexico), Carlos Capelán (Uruguay/Sweden), Shilpa Gupta (India), Hiwa K (Iraq/Germany) and Sangeeta Sandrasegar (Australia). While the trace may at first seem imperceptible, the artists carefully summon it as both idea and action; a concept and a material.

Formally The Tangible Trace occupies many mediums – installation, video, painting, monoprints, pressings, photography, mappings – but it’s the shared dialogues and concerns that are crucial: personal and collective memory, displacement and refuge, war and conflict, history and passing time, the production of cultural knowledge, surveillance, and the experience of bodies moving through cities.

Now in its third iteration, the TarraWarra International series has always sought to foster a global dialogue between artists, yet this year’s exhibition seems particularly pertinent in light of the current worldwide discourse on global movement and displacement, alongside an intensifying, twisted nationalism. For a show centred on quietness, soft gestures and intuitive modes of experience and representation, it feels urgent.

Yet overt politics were not necessarily on curator Victoria Lynn’s mind when she began forming the show – instead the trace first emerged from artist Sangeeta Sandrasegar. “I was thinking about the work Sangeeta makes with shadows and the importance of presence and absence – the way that historically the shadow has been seen as a trace – and the exhibition grew out of that,” explains Lynn. Shadow and light are pivotal in Sandrasegar’s work, often exploring postcolonial contexts and marginalised communities – interests which are extended in the artist’s new installation Things fall from view (2019). Featuring large panels placed in TarraWarra’s vista space, the work complicates the museum’s picturesque views and uses botanical dyeing marks to trace both the cultural history of colour and post-colonial relations between India and Australia. Physically, the panels will create fluctuating shadows that, as Lynn explains, “work with the idea of journey as a kind of trace of presence in space, and through the city.”

Both Gill and Sandrasegar illustrate how The Tangible Trace works obliquely, rather than directly. For Lynn this is a natural progression from the 2017 TarraWarra International All that is solid… “A lot of the artists in that show were working with the archive and fragments, working with the idea of memory and specifically working with actual archival information,” says the curator, who began considering the ways artists work with memory and materials beyond archival structures. She speculated that the flipside of the archive could be the trace. While All that is solid… troubled the archive, the concept of tracing allows for more intuitive and less formal ways of working with materials, memories and places.

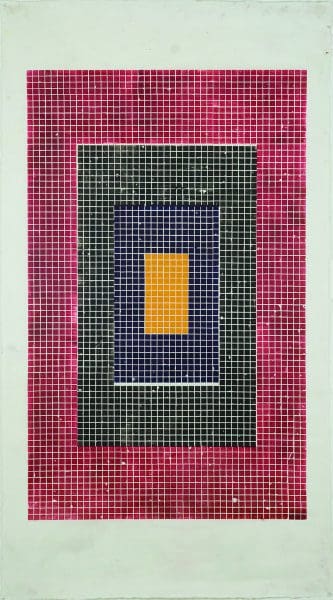

Two-dimensionally this is represented through a new series of paintings by Carlos Capelán. Working in reference to geometric and cubist styles, Lynn suggests that “Carlos traces portraits that are kind of ghosts, or apparitions from the past.” In addition, Shilpa Gupta is also creating two new works; one is a large stone with multiple language tracings which will be broken into fragments that viewers are encouraged to take, while the second continues the artists’ mapping of copper.

The links between place and memory are further enmeshed in Hiwa K’s video work Pre-Image Blind as the Mother Tongue, 2017, which stems from the artists’ experience of journeying, illegally and by foot, to Europe. In the piece, Hiwa K balances a prop made of motorbike mirrors on his nose. Looking upward to balance the construction, the artist uses the mirrors to navigate his way through the city, with the mirrors further reflecting his journey. Viewers also look upwards into the mirrors to view the reflections of Athens, which was one of the cities Hiwa K passed through when journeying from Iraq. “In a way Hiwa K is retracing his original steps that he took as a young man fleeing Kurdish Iraq,” explains Lynn. “But he’s also conscious of the watching, the looking and the surveilling that happens now when refugees walk through some of these cities on their way to other countries. There’s a sense of multiple echoes of the trace in his work.”

Meanwhile Francis Alÿs, a Belgium-born artist who resides in Mexico, considers place and experience through video works on the crises and displacement caused by drug trafficking and turf wars in Mexico. While one video documents the artist kicking a fiery soccer ball through the streets of Ciudad Juárez, another follows Alÿs as he walks at night through the city’s pathways, with another fiery ball as the guiding light.

What becomes clear in The Tangible Trace is how the continual emphasis on place ultimately draws attention to displacement. “Not to be too biographical,” says Lynn, “but I think they’ve [the exhibiting artists] all experienced a sense displacement, if you like, in their lives.” For the curator, the tracing of displacement is a way of reexperiencing and representing a situation or moment: “The trace is a way of memory coming back.” Here the trace becomes a strategy; a way for artists to deal with their experiences of the world around them.

Taking a step further, the empathies between the artists ultimately gravitate toward loss – whether of a situation, experience, place or loved one. “How do you hold onto that loss?” asks Lynn. “You can’t hold onto losses in their entirety. You can hold onto them either through the archive, which is the formal way in which you document the situation, or through the idea of the trace.”

TarraWarra International 2019: The Tangible Trace

TarraWarra Museum of Art

8 June–1 September

This article was originally published in the May/June 2019 print edition of Art Guide Australia.